Why the Fed Is Ending Its Big Covid Break for Banks

Why Fed’s Covid Break for Banks Now Has It in a Bind

(Bloomberg) -- After markets gyrated in March 2020, the U.S. Federal Reserve pumped trillions of dollars into a financial system rocked by the coronavirus pandemic. It also gave banks a one-year break from a rule it feared could make them pull hundreds of billions out of the economy at an inopportune time. As the March 31 end of the waiver to something called the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) approached, many banks argued that it should be extended, lest they be forced to retrench while the economy is still fragile. Bank critics, including Senator Elizabeth Warren, pushed to end the break, noting that banks were managing to return tens of billions to shareholders through buybacks and dividends. The Fed decided to let the waiver lapse, but said it would propose other ways of addressing the banks’ concerns.

1. What’s the supplementary leverage ratio?

It’s a standard developed by global bank regulators after the 2008 financial crisis. It requires banks to set aside more capital as their assets grow. Unlike pre-crisis rules, it does not allow banks to adjust the capital reserve according to their judgment of the riskiness of their holdings -- that is, holding safe assets like Treasuries doesn’t reduce the requirement.

2. What happened in March 2020?

So much! As the scope of coronavirus lockdowns became clear, asset prices plunged and markets began to seize up, including the Treasuries market, seen as a linchpin of the global financial system. Along with cutting interest rates to near zero, the Fed began massive, rapid purchases of Treasuries and other securities.

3. What did that have to do with banks?

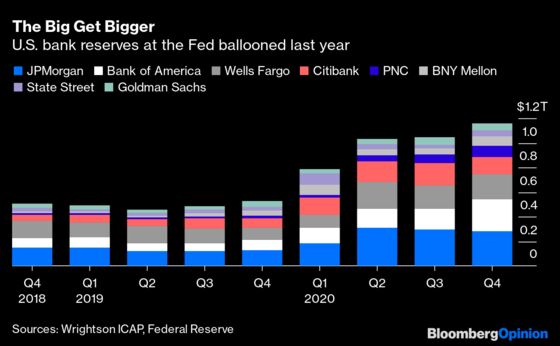

When the Fed purchases Treasuries from a money manager, those securities become an asset on the central bank’s balance sheet. The seller deposits the cash it received at a bank, and the bank in many cases adds it to the reserves it holds at the Fed. That makes the money an asset for that bank and a liability for the Fed. In other words, the Fed’s big purchases boosted the asset levels of U.S. banks. If the SLR had been left in place, those increased assets would have meant that banks needed to set aside more capital as reserves.

4. Why would that have been a problem?

The last thing the Fed wanted during that critical time was for banks to be pulling money out of the economy. So it eased the SLR so that banks’ excess capital could be deployed to struggling businesses and households. The continuing disruption in Treasuries was also a major factor in the decision. The move allowed banks to help stabilize that market, while maintaining funding for short-term borrowing arrangements known as repurchase agreements.

5. What was the argument for an extension?

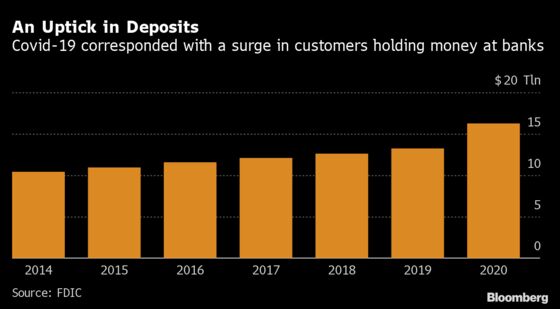

Wall Street pointed out that the pain from coronavirus is far from over. JPMorgan Chase & Co. cautioned that it might have to shun customer deposits if tougher rules are reinstated -- an awkward situation just as the big Covid relief bill signed by President Joe Biden in mid-March pumped billions into consumers’ accounts. Analysts have also tied recent bouts of wild trading in the $21 trillion Treasury market tied to concerns that banks will be forced to hold less government debt, even potentially selling hundreds of millions of dollars of their holdings. By some measures, the SLR break allowed banks to expand their balance sheets by as much as $600 billion.

6. What was the argument against that?

In the minds of some, the Fed created its own political problem by loosening the restrictions on banks’ cash distributions it had put in place early in the pandemic. Banks were now buying back stock and distributing capital to shareholders, or, in SLR terms, willfully reducing their numerator. It stood to reason, then, that they could afford to have the denominator return to its usual form. That was the argument from Warren and her fellow Democratic senator, Sherrod Brown. In a letter to regulators, they argued “to the extent there are concerns about banks’ ability to accept customer deposits and absorb reserves due to leverage requirements, regulators should suspend bank capital distributions. Banks could fund their balance sheet growth in part with the capital they are currently sending to shareholders and executives.”

7. What did the Fed do?

It concluded the threat that Covid-19 poses to the economy isn’t nearly as severe as it was a year ago. But the agency also said that it’s going to soon propose new changes to the SLR to address the recent spike in bank reserves triggered by the government’s economic interventions. Central bank officials said they don’t want the industry’s overall capital levels to change. The Fed did provide another consolation, though, by more than doubling to $80 billion the maximum overnight reverse repo activity a participant can execute through the central bank’s facility. That could absorb some of the pressure of too much government stimulus cash sloshing through the system by giving money market funds a place to put it.

The Reference Shelf

- The Fed’s announcement of and interim guidance on the SLR waiver.

- The interim final rule issued by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

- The letter sent by Warren and Brown to regulators.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.