Why ‘Fallen Angels’ Are a Bond Market Preoccupation

Why ‘Fallen Angels’ Are a Bond Market Preoccupation

(Bloomberg) -- Xerox Corp. is the latest big-name American company to join an inauspicious club. Its bonds completed a fall from investment grade to junk status on Dec. 18, making them what’s known as “fallen angels.” There’s concern that the ranks of fallen angels will be growing in coming months, especially if the U.S. economy moves further toward recession.

1. What makes a fallen angel?

Generally speaking, a fallen angel is a bond that is downgraded to BB+ or below (junk) by at least two of the three major rating firms -- Moody’s Investors Services, S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings -- after being formally rated BBB- or higher (investment-grade). Downgrades can happen when a company isn’t creating enough revenue or generating enough cash to service its debt, or when it pursues financially aggressive policies to appease shareholders and takes on so much debt that its financial leverage -- debt as a percentage of the company’s overall capital structure -- becomes disproportionate.

2. What happens when bonds lose investment-grade status?

A fall to junk status, more politely called high-yield, affects borrowers and investors. For a company like Xerox, which relies on the capital markets to fund operations, downgrades make it more expensive to borrow. A company that slides all the way to junk may need to tack on debt covenants to the formal contracts with bondholders. These covenants protect investors who agree to lend to the now-riskier issuer and, often, prevent the company from benefiting shareholders at the expense of bondholders. Junk status also can force a wave of selling by investment companies and funds whose mandates prevent them from holding credit below investment grade. The prices on the bonds may need to fall to compensate investors for holding a less liquid, or actively traded, security.

3. Which companies might be next?

Ford Motor Co.’s debt trades like it’s speculative grade. PG&E Corp., the California utility facing billions in liabilities from the potential role it played in a huge recent wildfire, is on credit watch negative by S&P. Both companies are among the names on the hot seat. S&P’s global fixed income research group sees companies in the retail sector as the most vulnerable to becoming fallen angels. UBS, meanwhile, sees non-financial fallen angel debt -- which could reach as much as $100 billion if the cycle deteriorates -- as being concentrated in consumer non-cyclicals and energy.

4. Why are fallen angels in the news?

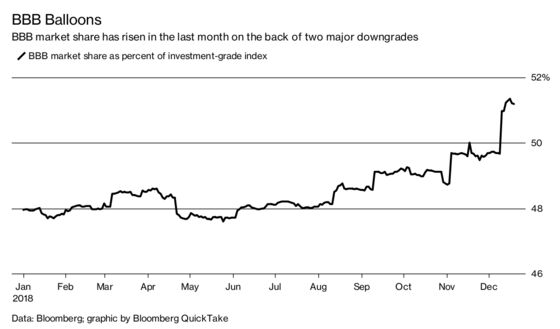

Companies like Ford and PG&E that are rated BBB- ("triple B minus"), the lowest rung before junk, comprise more than 14 percent of the $5 trillion investment-grade corporate index. (The BBB universe -- the three lowest investment-grade rungs -- has grown to represent more than half of the index.) Anheuser-Busch InBev NV and Lowe’s Cos. were downgraded into the space recently, the beer maker amassing over $100 billion of debt through acquisitions and the home-improvement company planning to ramp up leverage to buy back shares. General Electric Co. was downgraded to BBB in part because of weakening cash flows that may make it harder to manage a massive debt load. With the BBB rung as crowded as it’s ever been, and a growing amount of debt that will mature and need to be refinanced over the next few years even as interest rates rise, there are concerns that a turn in the economic cycle could trigger a series of downgrades.

5. Is everyone worried?

Not everyone sees an avalanche of downgrades to high-yield as a likely near-term scenario. In a Dec. 17 blog post, AllianceBernstein called for more of a "flurry" than a "blizzard" as the credit cycle turns and said that the process of losing investment-grade status could take years to play out for many issuers. According to strategists at Bank of America Corp., most of the BBB rated companies with large capital structures are "unlikely to become fallen angels" during and after the next recession. Barclays Plc analysts are more worried about downgrades within the investment-grade space than they are about fallen angels. That said, the BBB market has rung warning signs for many. "Unsustainable leverage" among companies in the space, per Guggenheim, "warrants heightened scrutiny."

6. Why has BBB gotten so crowded?

Historically low borrowing costs over the last decade allowed companies to issue debt and pursue aggressive growth strategies with little consequence. On top of that, leniency by the ratings agencies allowed companies to maintain investment-grade ratings despite elevated leverage ratios.

7. What would a mass downgrade mean for the economy?

Credit downgrades along with rising interest rates would increase the cost of debt capital, leaving businesses with less cash to invest. That could hamper economic growth. An overwhelming increase in fallen angels could also create disruption in credit markets, heightening fears of broader instability. Such an event might lead to "significant dislocations" and "disruptive repricing" in the high-yield market, per Guggenheim and AllianceBernstein, respectively. UBS sees fallen angel debt as rising to $150 billion to $175 billion in a recession, just short of 2009 levels.

8. Where did the expression ‘fallen angel’ come from?

A 1984 story in American Banker newspaper attributed it to David Solomon, head of Solomon Asset Management, which at the time was a leading investor in the emerging field of junk bonds. (He’s not to be confused with the current head of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.)

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on GE’s giant debt load, PG&E’s wildfire problem and how leveraged loans are and aren’t like junk bonds.

- Shouldn’t there be more fallen angels at this point?

- Bloomberg’s story on Xerox’s fall to junk grade.

- Xerox’s illustrious history includes becoming a verb.

To contact the reporters on this story: Brian Smith in New York at bsmith373@bloomberg.net;Natalya Doris in New York at ndoris2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christopher DeReza at cdereza1@bloomberg.net, Brian Smith, Laurence Arnold

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.