Why European Parliament Elections Suddenly Matter

Why European Parliament Elections Suddenly Matter: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- Elections for the European Parliament used to be dull affairs. This time is different. The continent-wide vote May 23-26 is shaping up to be something of a referendum on the whole 60-year European Union experiment, in part because the ballot comes amid Britain’s drawn-out departure from the bloc. An expected clash of values and policies will extend far beyond the assembly itself, with ripple effects on other European institutions and on national politics. With the U.K. required to take part because the country is still a member of the EU, British voters could also use the occasion to deliver a verdict on Brexit.

1. How is it that Europe’s future will be on the ballot?

In many countries, the role of the EU now dominates domestic politics too. And for the first time, there’s a real possibility that anti-EU parties could win enough seats to disrupt legislative business rather than just rail against it, as Nigel Farage of the U.K., Marine Le Pen of France and Matteo Salvini of Italy have done. Emmanuel Macron, who defeated Le Pen in the 2017 French presidential election, says the contest is a choice for or against Europe.

2. Who’s fighting against the EU?

Particular attention is on the EU Parliament’s euroskeptic faction led by Salvini’s League and Le Pen’s National Rally and whether they succeed in broadening their base. Salvini formed a campaign alliance with nationalist parties in Germany, Finland and Denmark and held talks with potential partners in Poland and Hungary. Even without new allies, this group’s share of seats will grow to 8% from 5%, according to an April 18 projection published by the assembly. Traditionally, euroskeptic forces have been divided and failed to form a single bloc.

3. Who squares off against the euro skeptics?

Most candidates run under the mantle of domestic parties that are part of European political families, like Christian Democrats (home of German Chancellor Angela Merkel) or Socialists (encompassing the party of Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez). This facilitates the forming of alliances in the EU Parliament after each election. That’s why Salvini has tried to unite nationalist forces across EU countries under a common program, while Macron’s Republic on the Move party chose to campaign in a coalition with Europe’s Liberal political family.

4. What do the anti-EU parties want?

Generally, they’ve moved away from rhetoric about destroying the EU to insisting on taming it, for instance by restoring internal borders. Steve Bannon, the onetime chief political strategist of U.S. President Donald Trump, set up a Brussels-based organization called The Movement to provide polling support to populist parties that favor national sovereignty and immigration curbs. More sensitive to the risk of election meddling by anti-EU forces, the bloc is introducing financial penalties against European political parties and foundations that misuse personal data in the campaign. At the same time, Facebook Inc. Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg has called for new global rules on the Internet in a bid, among other things, to ensure the integrity of elections.

5. What is the impact on national politics?

The EU ballot is also widely regarded as a verdict by voters on their national governments, serving as a rehearsal for domestic elections and sometimes even as a catalyst for political changes in countries. This time, for example, the results in Italy and Germany could shake their ruling coalitions. The question is whether Salvini’s League will become emboldened enough to abandon its awkward partnership with the left-of-center Five Star Movement and whether Germany’s Social Democrats react to projected losses by concluding that their role as junior partner in Merkel’s government is a liability.

6. How is the campaign shaping up in the U.K.?

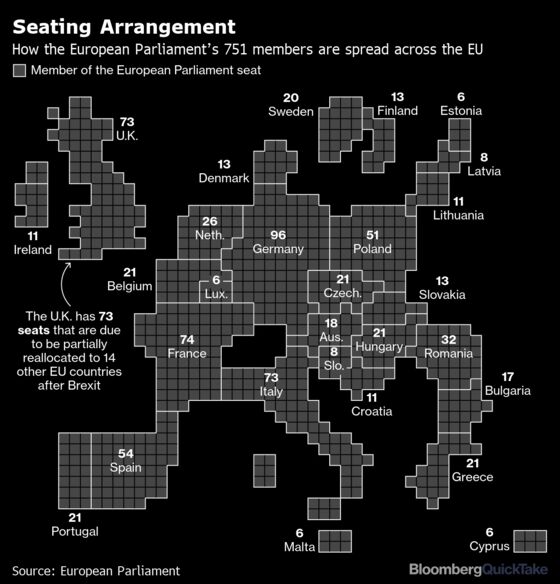

As Prime Minister Theresa May continues to struggle to reach a deal with the U.K. House of Commons on leaving the EU, British politicians campaigned for the country’s 73 seats in the bloc’s Parliament since mid-April. That’s when Britain’s EU departure deadline was delayed until Oct. 31, and EU law requires every member country to have representatives in the European assembly. Opinion polls showed Farage’s newly formed Brexit Party soaring as he tapped anger that Britain is still in the EU almost three years after the nation’s historic referendum to leave the bloc. Another new party called Change UK, created by Conservative and Labour defectors, backs a second referendum on withdrawing from the EU.

7. How does the European ballot work?

Seats in the European Parliament are contested across the EU, with most member nations functioning as single constituencies. The assembly’s size has grown over the years to 751 seats as the EU expanded to more than 500 million people. The U.K.’s planned withdrawal -- whenever it happens -- will reduce the number of seats to 705. Each country has a share proportionate to its population; some nations might also hold national or regional elections at the same time. The twice-a-decade vote is one of the biggest democratic exercises on Earth. Within each country, seats are awarded to parties according to the proportion of votes, a system that paves the way for insurgent national groups to harvest protest ballots.

8. What is the European Parliament, exactly?

It’s like the lower house of a bicameral legislative branch -- the EU’s version of the U.S. House of Representatives or the U.K. House of Commons. In the EU case, however, the upper house isn’t an assembly of individuals but rather the governments of member countries. The European Parliament helps govern the EU as its only directly elected institution, countering criticism that the bloc is a project driven by elites. The assembly grew out of a body that dated back to the 1952 European Coal and Steel Community, the EU’s precursor, with members being appointed by the bloc’s national parliaments before the first direct elections took place in 1979.

9. What are its powers?

It decides on the EU’s 140 billion-euro ($157 billion) annual budget and crafts European laws on everything from banker bonuses and electricity flows to car emissions and e-cigarettes. It approves the leadership of the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, which is due to start a new term in November. It has veto authority over EU trade agreements. It passes resolutions and organizes hearings on issues of public interest. While lacking a serious role in traditional foreign-policy matters, the body also acts as a barometer of public opinion in Europe and can agitate for action by the commission and national governments in external as well as domestic affairs.

10. Does it ever make front-page news?

The EU Parliament came of age politically in 1999 when it forced the resignation of the entire European Commission leadership team under then-President Jacques Santer because of a scandal affecting France’s appointee. Since then, it has continued to gain legislative powers through European constitutional changes and political clout through assertiveness. The last two commission presidents have been forced to make changes to their leadership teams as a result of Parliament objections to individual nominees. On the legislative front more recently, the assembly successfully agitated for and then endorsed a proposal to end the biannual seasonal clock change in Europe.

11. Have voters had enough of the EU?

A European Parliament survey published in April on citizens’ attitudes toward the EU found that -- excluding the U.K. -- 61% regard their country’s membership in the bloc to be a good thing. An even higher percentage -- 68% -- said they believe their nation has benefited as a result. On the other hand, many EU citizens view lawmakers and bureaucrats in Brussels with suspicion and pay much more attention to national personalities. In the last EU legislative election, in 2014, voter turnout hit a record low of 42.6%.

The Reference Shelf

- Story on Nigel Farage launching his Brexit Party’s campaign.

- A QuickTake on the global rise of populism.

- A look at whether EU populists can be a force in the EU parliament.

- How Italy’s Salvini is trying to take back initiative in EU election.

- European Parliament survey of public attitudes toward the EU.

- A look at Bannon’s The Movement by Leonid Bershidsky.

- The EU experiment with replicating national parliamentary democracies.

- How Macron’s “Renaissance” aims to shake up the European Parliament.

--With assistance from Ian Wishart.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jonathan Stearns in Brussels at jstearns2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Ben Sills at bsills@bloomberg.net, Melissa Pozsgay, Flavia Krause-Jackson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.