Why Europe’s Pandemic Recovery Deal Is a Big Deal

Why Europe’s Pandemic Recovery Deal Is a Big Deal: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) --

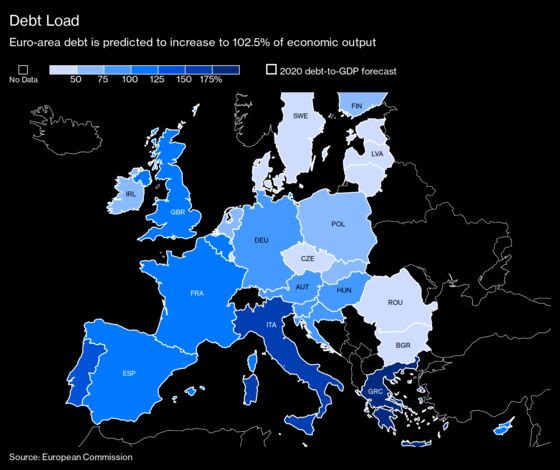

When Italy and Spain became early pandemic hot spots in March, it looked like the virus might claim another victim: the cohesion of the European Union. German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the Covid-19 outbreak represented the most serious existential threat the EU had ever faced. The risk was that the political bloc’s 27 nations, seeking a united response to the deepest recession in generations, would be torn apart by old divisions — notably between richer northern nations and the southern countries worst-hit by the pandemic. Instead, they came together to agree on a jointly funded recovery plan.

1. Why was the threat so great this time?

Because the scale of the crisis meant the often-bickering, fractious states in the bloc had to come up with a huge common economic rescue plan. Without one, the stability of the region was in doubt, according to the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm. French President Emmanuel Macron warned that a failure to direct funds where they are most needed would boost anti-EU populists. Italy and Spain — which have some of the highest coranvirus death tolls — came into the crisis with weaker economies and higher debt and unemployment. That means they are unable to match the spending power of the likes of Germany, which announced massive stimulus programs and showered its firms with bailout funds.

2. Why doesn’t the EU simply divert existing funds?

The EU is not a single country. It doesn’t have a common treasury that’s expected to support regions in need, the way the U.S. Treasury pours funds into states hit by disasters such as hurricanes. Nor does it have anywhere near sufficient funds in its relatively meager common budget to deal with this crisis. Even in the euro-using core, monetary union is not backed by real economic or banking unions. As the EU’s devastating debt crisis of 2010 showed, in tough times money tends to fly to the continent’s safe harbors, exacerbating liquidity crunches in the economically weaker countries as their borrowing costs surge. The pandemic triggered loud calls for immediate burden-sharing, with the idea floated (and quickly squashed) that the EU should consider pooling the debt obligations of its member governments into what was dubbed “coronabonds.”

3. What did leaders agree on instead?

A 750 billion-euro ($850 billion) emergency fund that will give out 390 billion euros of grants and 360 billion euros of low-interest loans. The money will come from bonds sold on behalf of the EU as a whole, with repayments out of the EU budget, to which Germany contributes the lion’s share. The plan marked a dramatic shift for the Germans, who traditionally have opposed any form of so-called mutualized borrowing. It faced objections from Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, the so-called Frugal Four, which were skeptical of a major borrowing spree that could leave their taxpayers on the hook for decades. Those countries managed to whittle down the level of grants from the original proposal of 500 billion euros made by Merkel and Macron. Almost a third of the recovery fund is earmarked for fighting climate change.

4. Is this a ‘Hamilton moment’?

Not exactly. A so-called Hamilton moment -- as happened in the U.S. in 1790 -- whereby obligations across all 27 member countries are mutualized would require treaty changes adopted by national parliaments and in some cases referendums. So far, there’s no sign of majority backing for reform that would cede national sovereignty by giving a central authority the power to raise taxes and decide how money is spent throughout the EU or even the 19 countries that use the euro. Even so, a unanimous decision to let the EU’s executive arm issue more debt on behalf of the entire bloc was seen as a decisive step forward in the European integration process.

5. Is the EU edging closer to debt mutualization?

Germany says the recovery fund does not represent debt mutualization but is a one-off concession for the duration of the crisis. Even so, the bloc’s members have progressively shared increasing levels of risk and have bailed each other out in times of need. The European Stability Mechanism -- the euro area’s crisis fund -- has raised hundreds of billions on debt markets, allowing Greece -- the EU’s most indebted state -- to save billions on interest payments. The same arrangement is also available now for countries wishing to draw up to 240 billion euros from the fund to finance costs related to the pandemic. Also, the European Central Bank has been buying massive amounts of debt under its bond-buying programs, making its shareholders -- euro-area members -- in theory liable for any losses. According to Berenberg Chief Economist Holger Schmieding, the EU and the countries that use the euro are not en route toward fiscal union, “but they are taking a significant step towards stronger fiscal coordination when it matters.”

6. What does it mean for the bond market?

Joint issuance will rise to 14% of sovereign bonds in the euro area, up from 8% before the plan, according to Berenberg. Such debt, buoyed by the EU’s AAA rating and strong demand for safe assets, may develop into a more suitable regional benchmark than German bunds. The 10-year bund yields about -0.45%, while Italy’s pays around 1.1%. EU-issued debt would yield something in between, about -0.25%, said Peter de Coensel, chief investment officer for fixed income at Degroof Petercam Asset Management in Brussels. To become the European equivalent of U.S. Treasuries, the EU would need to offer tenors as long as 30 years and ensure ample liquidity.

7. So might the virus bring more unity?

The emergency funds serve as validation that the bloc can offer meaningful solidarity to members in need. Charles Michel, president of the EU leaders’ council, described the agreement as “as a pivotal moment in Europe’s journey.” To be sure, other forces could still shake the EU’s foundations. A German court ruling has challenged the authority of the European Court of Justice as the ultimate arbiter in the bloc. That may encourage similar steps by the illiberal governments in Poland and Hungary, which have been accused of seeking to upend two core EU principles: the rule of law and checks and balances.

8. Isn’t the EU always in crisis?

It seems that way. There was the failure to pass a European constitution followed by the sovereign debt crisis. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees in 2015 found the EU unprepared and sparked a populist backlash. A year later, the U.K. voted to leave the bloc, raising the specter that other countries might follow. One theory is that the crises are interconnected, with each feeding into the next — what former European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker called a “polycrisis.” What’s more, national governments answer to their own voters and need to abide by constitutions and parliaments, which can undermine efforts to make strategic decisions about the bloc as a whole. Critics warn that the EU will face a long struggle if leaders persist on defending national interests above the common good. Yet doomsayers have consistently underestimated the will of Europe’s establishment to keep together what is one of the world’s biggest free-trade areas, created from the ashes of World War II with a vow to never let such a calamity happen again.

The Reference Shelf

- The recovery fund is historic even if it falls short of “Hamiltonian,” writes Bloomberg Opinion’s Lionel Laurent. Columnist Andreas Kluth says the deal might not be enough to save the European dream in the long run.

- QuickTakes on coronabonds, banking union, the euro’s flaws and the “Brussels effect.”

- EU’s survival instinct overcomes frugal dissent, writes Bloomberg economist Maeva Cousin.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.