Why Electric-Powered Airplanes Are Headed for Takeoff

Why Electric-Powered Airplanes Are Headed for Takeoff

(Bloomberg) -- In Sweden they call it flygskam, or flying shame -- the guilty feeling that you’re helping destroy the planet when you zip off to Spain for the weekend. Airlines and planemakers are acutely aware that one day they may face a backlash from climate-conscious customers, as well as tougher government regulations. That’s why they’re seeking ways to cut pollution and reduce their carbon footprint, including by developing electric and hybrid planes. There’s hope that some day electric technology can do for the skies what Toyota Motor Corp.’s groundbreaking Prius hybrid car did for the roads.

1. Are electric planes even possible?

Yes, but they have to start small. Los Angeles-based startup Ampaire Inc. has taken an early lead by converting a six passenger Cessna 337 into a hybrid model with both a conventional combustion engine and an electric motor. Ampaire says the plane, dubbed the Electric EEL, could enter service by 2021 and cut fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by 50%. Israeli rival Eviation Aircraft Ltd. displayed an all-electric nine-seat prototype at the Paris Air Show in June 2019 and is aiming for short-range commercial flights within three years. In all, says consultancy Roland Berger, there are about 100 different electric aviation programs under development around the world. But the bigger the plane, the higher the hurdles: Airbus SE has floated the possibility of introducing a hybrid version of its best-selling single-aisle A320, which seats up to 240 people -- but not before 2035.

2. What’s the challenge?

The big problem for electric motors is the size and weight of the batteries needed to power them. Current lithium-ion batteries store only a small fraction of the energy in an equal volume of liquid jet fuel. That makes them too inefficient for large or long-distance electric planes. Plus, unlike liquid fuel, their weight doesn’t diminish as the flight progresses. Hybrid technology mitigates that by using both conventional and electric engines. Either they share the workload or the conventional engine charges the batteries; in both cases, emissions are lower and the batteries can be much smaller. In some hybrid designs, electric engines are used to power the short but heavily polluting takeoffs and landings, while at cruising altitude, propulsion is provided by conventional jet engines designed to be more fuel-efficient mid-flight.

3. How does that compare to a Prius?

Toyota’s Prius, introduced in 1997, uses what it calls “full” hybrid technology that connects an electric motor powered by batteries and a conventional engine powered by gasoline. They can work together or separately, and the gas engine also charges the batteries. Airplane engine maker United Technologies Corp.’s Project 804 is testing a slightly different “parallel” system. The company has re-engineered a Bombardier Dash 8 aircraft with an electric motor for supplemental power during takeoff and ascent and a conventional engine for cruising. In this design, the battery isn’t recharged by the jet. The Airbus A320 project employs a “serial” approach that uses a battery-powered motor for takeoff, flying and landing. A conventional engine recharges the batteries.

4. What’s driving the electric push?

Unlike cars, which have long had to adhere to rules on exhaust, neither airplanes nor the companies that fly them are currently subject to binding greenhouse gas emission limits. The aviation industry accounts for about 2% of such emissions today, globally, though surging passenger numbers mean it could become a much bigger source of pollution in the future.

5. Could emissions really be lower?

That depends. As with cars, the carbon footprint of a hybrid-electric plane depends on how much it uses electric power and the source of the electricity. A plane that charges its battery midair by burning jet fuel won’t reduce emissions much. But all-electric designs and “parallel” hybrids charged before takeoff using electricity from renewable energy sources could make a real difference. Still, for the next few decades the total potential pollution reductions are limited. A study published in the magazine Nature in 2018 estimated that with current technology, electric or hybrid planes with a range of up to 690 miles (1,110 km) could handle half of all flights and reduce aviation’s carbon emissions by 15%. Deeper cuts would depend on the development of batteries that can store more power per pound.

6. How soon might electric planes be in the air?

Small robotaxis are poised to take off first, with the first commercial electric models -- possibly autonomous or semi-autonomous -- scheduled to hit the market in 2020. The Chinese-made RX4E, an all-electric four seater, made a test flight in October. Small hybrid-electric planes ferrying 10 to 20 passengers could arrive by the middle of the next decade and bigger regional-sized aircraft carrying many as 40 passengers around 2030, according to Stephane Cueille, chief technology officer at Safran SA, a top jet engine maker.

7. What about big passenger planes?

Full-size commercial airliners will need much longer: the Airbus project mooted at the Paris Air Show in June will take at least 15 years to reach fruition. The European aerospace giant is working with Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc on developing a hybrid engine, though that power plant, due to be tested in the next two years, would produce just 2 megawatts of power, far less than what’s needed to propel even a small narrow-body model. Purely electrical propulsion is much further out, given that batteries are too heavy to achieve the same efficiency as fuel. Safran estimates that full-size battery-powered commercial aircraft are not feasible before 2050 at the earliest.

8. Who else is working on this?

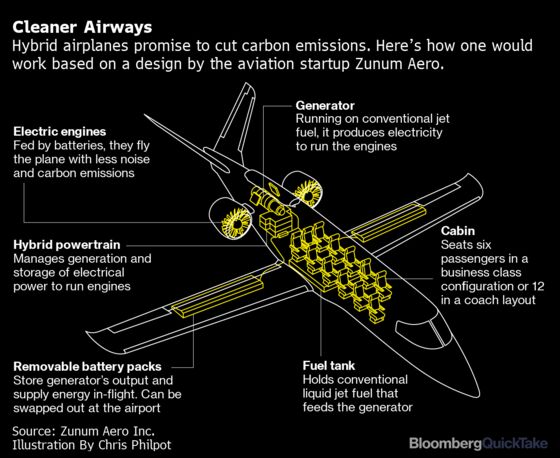

EHang Air Mobility Group of China says it will start selling a $300,000 aircraft next year and anticipates strong demand from emergency responders, air taxi services and operators of tourist flights. Germany’s Volocopter GmbH, which is backed by Daimler AG, this year will open a “Voloport” in Singapore for public test flights and expects commercial service as early as 2021. Israel’s Eviation is planning a first flight early next year in the U.S. of its Alice model, followed by the assembly of more planes in Arizona and Washington state and certification around 2021. Other startups chasing the opportunity include U.S.-based Zunum Aero, MagniX Technologies Pty Ltd and the U.K.’s Faradair.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg: Why Airbus might make one of its best-selling planes a hybrid.

- Meet the Israeli company making electric-powered commuter planes: Bloomberg

- Businessweek: Six flying robotaxis that could soon take you from midtown to JFK.

- Flying taxis of the future look like kids’ toys come to life: Bloomberg.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Adam Minter on the future of electric airplanes and Chris Bryant on flight shame and high-speed rail.

- YouTube video about the test flight of a hybrid-electric plane in the U.K.

- Websites for Ampaire, Eviation and Faradair.

To contact the reporters on this story: Benedikt Kammel in Berlin at bkammel@bloomberg.net;Oliver Sachgau in Munich at osachgau@bloomberg.net;Tara Patel in Paris at tpatel2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anthony Palazzo at apalazzo@bloomberg.net, Christopher Jasper, Andy Reinhardt

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.