How China’s Trying to Woo Foreigners to Buy Bonds

Why China’s Bond Market Is About to Get Less Exotic

(Bloomberg) --

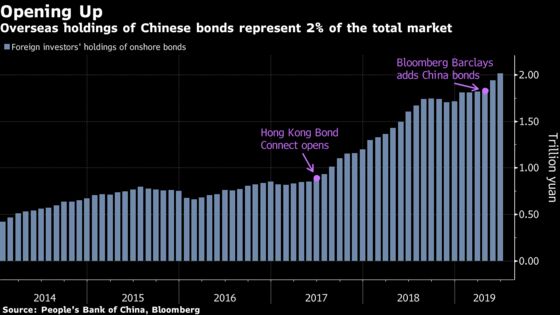

Little by little, China is winning more recognition from global bond investors. Bloomberg Barclays began adding Chinese sovereign debt to its aggregate index in April and JPMorgan Chase & Co. will start including some in February next year. FTSE Russell has China on a watchlist for possible inclusion in one of its benchmark indexes. For international funds that track them, such moves highlight the maturing of China’s $13 trillion debt market, the world’s second-biggest after the U.S. It’s a market with returns that stand out in a world awash with more than $15 trillion of negative-yielding debt, but which has struggled to lure foreign investors even in a banner year for global fixed income. Overseas funds -- whose holdings remain a drop in the bucket at just over 2% of the total -- raise concerns about such things as market liquidity, hedging options and China’s yuan currency itself.

1. What are the details?

Bloomberg Barclays’s Global Aggregate Bond Index, which tracks about $56 trillion in debt, began in April a 20-month process of adding sovereign bonds and notes issued by three Chinese policy banks, which finance state projects and economic and trade development. Upon completion, 356 Chinese securities will account for more than 6% of the index. (Bloomberg Barclays is owned by Bloomberg LP, which also owns Bloomberg News.) JPMorgan’s GBI-EM indexes track more than $200 billion of bonds issued by emerging market governments. They will start adding nine of the most-liquid Chinese government bonds over a 10-month period beginning Feb. 28. While FTSE Russell passed in September on adding Chinese debt to its World Government Bond Index, which tracks $20.5 trillion of debt, it said it sees “significant progress toward a future upgrade.” It will announce the results of its next major review in March 2020.

2. Why is it important?

All indexes track the value of a designated group of financial instruments. For example, the S&P 500 Index tracks a list of major U.S. stocks. Being included in an index should lead to a sustained increase in purchases from passive funds that replicate the benchmarks in their portfolios.

3. What does it mean for China?

Chinese officials have sought to encourage steady inflows of global funds into the domestic market, in part to help balance pressures on the yuan after an exodus of capital in 2015. Foreign investors have bought about $40 billion of China’s bonds this year through August. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts estimate that JPMorgan’s move could lead to a further monthly inflow of about $3 billion, and that inclusion in the bigger WGBI gauge could bring in twice that. UBS Asset Management has said that flows directly tied to the inclusion of China in the three major benchmarks could reach $500 billion during the next two years. That, it said, may encourage greater issuance of Chinese bonds onshore, extra traffic that may jolt active money managers to look beyond the offshore market where many focus their attention now.

4. Why did China want this?

It’s not just the money. This is a big step in the Chinese government’s push to modernize its financial markets and increase the yuan’s global usage. Inclusion serves as a seal of approval for efforts such as allowing investors to allocate block trades across portfolios, clarifying some tax collection policies and aligning its settlement cycle more closely with global markets.

5. What’s the investor reaction?

Tepid so far, even though China’s 10-year government bonds was yielding 3.14% as of Sept. 27, compared with 1.6921% on equivalent U.S. Treasuries and -0.249% on Japanese government bonds. Any investors hoping that a wave of capital would drive bond yields significantly lower after April were disappointed: Chinese 10-year bond yields rose by 7 basis points from April through Sept. 27, the worst performance among 19 major bond markets tracked by Bloomberg News. By contrast, corresponding U.S. government bond yields fell more than 70 basis points. Global funds could already invest via programs known as Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors, which requires licenses from securities and foreign-exchange regulators. In September, the government removed the $300 billion ceiling on investments that could be made under those programs -- even though about two-thirds of the quota was still unused.

6. What’s holding them back?

Global asset managers have several gripes: One of the most common is China’s capital controls, which they fear could make it difficult to withdraw money in the event of a crisis. The shock devaluation in 2015 was followed by tighter capital curbs and sudden spikes in borrowing costs. Renewed weakness in the yuan this August was more orderly, but the U.S. still designated China a currency manipulator, an accusation China denied. Market liquidity is thin: It can be hard to buy some government bonds or corporate notes because the commercial banks that dominate China’s fixed-income market tend to buy and hold. (That’s one reason FTSE Russell gave for its decision and also what JPMorgan said to explain why it included only a handful of bonds.) Another drawback is that China lacks interest-rate derivatives to meet the hedging needs of foreign investors, who are also barred from trading government bond futures. Other challenges include the dubious credit ratings assigned by Chinese graders, which the government is trying to address by bringing in more foreign assessors.

7. How else do foreigners buy in?

Earlier efforts to open up the debt market included the Bond Connect, a channel for overseas investors via Hong Kong that started in July 2017, a year after the People’s Bank of China allowed most foreign financial institutions to invest in the interbank bond market, or CIBM. The downside was that it can take months to complete the registration process and it may require adding mainland staff or local offices. Bond Connect, in theory, allowed investors to skip that red tape, but in practice many found themselves held up.

8. What about corporate bonds?

FTSE Russell has said it intends to start assessing whether to include Chinese corporate bonds in some of its indexes, but it may be some time before that happens. Investors have a long list of complaints they would like to see resolved there too, including disclosures that differ between Chinese and English and a lack of clarity over bankruptcy laws.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Markets looks at the changing Chinese attitudes to defaults.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Nisha Gopalan weighs in on China’s sovereign wealth fund, and Shuli Ren sees the PBOC on steroids.

- More QuickTake explainers on progress in China’s financial sector opening, hedging tools, why China wants overseas buyers of its debt, and record corporate bond defaults.

- An outside view on what bond markets reveal about China’s economy.

--With assistance from Claire Che, Will Davies and Livia Yap.

To contact the reporters on this story: Gregor Stuart Hunter in Hong Kong at ghunter21@bloomberg.net;Tian Chen in Hong Kong at tchen259@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christopher Anstey at canstey@bloomberg.net, ;Sofia Horta e Costa at shortaecosta@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.