Why China Could Be Serious About a Property Tax Now

Why China Could Be Serious About a Property Tax Now: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- Private home ownership in China only began in 1998, yet prices have skyrocketed so much that a place to call their own is becoming increasing unaffordable for many people. The government has tried for years to address the problem by going after speculators. Now, amid a broad effort by President Xi Jinping to address widening social inequality, authorities are revisiting an idea long-discussed but never realized: imposing a property tax. If implemented, such a tax could have far-reaching implications for the country’s 300 million-strong middle class.

1. Why do we think it might be coming?

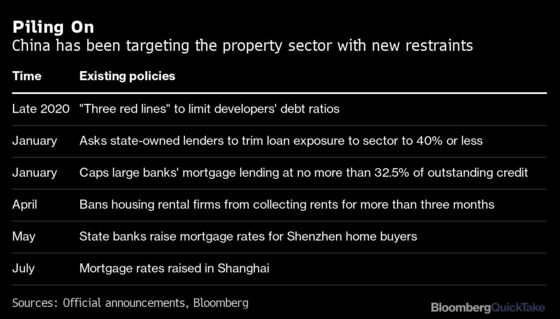

Legislators and officials from finance and housing ministries and the tax administration held a seminar in May on a new trial program in Beijing to hear from local officials and scholars. It marked the first time high-level policy makers collectively discussed the trial, which would cover both the land and structure in line with the global standard. That same month, Finance Minister Liu Kun said China aims to advance tax reform legislation by 2025. It was the second time he brought up a property tax in less than six months. There also have been escalating curbs on the real estate sector, from “red lines” on borrowing by developers to increases in mortgage rates in some cities. More broadly, the government seems to be on a campaign to try to ease financial pressures on the middle class, from restricting expensive after-school tutoring to ordering higher wages for gig-economy workers. Bringing down house prices with a new tax would fit that priority.

2. How does the system work now?

There’s an annual tax on commercial property but not most residential assets. Local governments do earn income from land sales to developers -- 8.4 trillion yuan ($1.3 trillion) last year, almost as much as the 10.1 trillion yuan raised mainly from other sources including sales taxes and personal and corporate income taxes.

3. Where’s it being tried?

Since 2011, the municipal governments in two cities, Shanghai and Chongqing, have been conducting property tax trials, levying an annual charge on second homes or high-priced ones (but not the land). The tax rate in Shanghai is set between 0.4% to 0.6% of the last-sale price. (In the U.S., such levies can reach as high as 2.13% in places like New Jersey.) Shanghai’s property tax revenue amounted to 19.9 billion yuan last year, according to the city’s tax authority. That’s only about 7% of its income from land sales, according to Bloomberg calculations based on official data.

4. What implications could a property tax have?

A little or a lot. Setting the tax low won’t bring down house prices much, while charging too much could cause an economic crash. Real estate investment accounts for 13% of China’s economy, from just 5% in 1995, according to Marc Rubinstein, a former hedge fund manager who now writes about finance. In a worst case scenario it could stoke social unrest; more than 70% of China’s household wealth is tied up in the property market. Policy missteps could have unintended consequences for the banking system. Chinese banks had over 50 trillion yuan ($7.7 trillion) of outstanding loans to the real estate sector, more than any other industry and accounting for about 28% of the nation’s total lending. Of those loans, about 35.7 trillion yuan were mortgage loans to households and 12.4 trillion yuan were for property development, according to official data. New home sales last year in China totaled $2.6 trillion -- a figure that’s grown more than threefold over the past decade.

5. How expensive is housing?

Affordability in hot cities such as Shenzhen and Beijing is only a notch or two better than Hong Kong, which is often named the world’s most expensive housing market. The average cost of buying an apartment in Shenzhen is 43.5 times the average annual salary for local residents, according to a 2020 study by E-house China Research and Development Institute. (The methodology didn’t specify the apartment size.) Unit prices there have tripled over the past decade, to 26,297 yuan per square meter from 8,201 yuan in 2009. The price-to-income ratio has worsened this year across China due to further price gains, according to research by the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu.

6. Why do people keep buying?

China’s middle class has lacked alternative investment options. State lenders offer relative low interest rates on deposits, while financial services including mutual funds and retail wealth management are only just taking off. Many buyers also see property as way to guard wealth against inflation. In addition, Chinese parents, like those elsewhere, fight to buy homes in good school districts to ensure better education for their children. Real estate was the biggest driver of gains in household assets in the first quarter of 2021, according to the Southwestern University research. While that’s broadly been the case for a long time, it’s becoming more acute this year.

7. What makes people think a tax will really happen this time?

Zhu Baoliang, chief economist at the State Information Center, a government-backed think tank, was quoted in August as saying China shouldn’t miss the opportunity to press ahead with a property tax. Another signal came in Vice Premier Han Zheng’s comments on steering away from using real estate to provide short-term boosts for the economy. Zhang Qiguang, an official for the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, said in July that bureaucrats in cities that experience rapid spikes in housing prices will be held accountable. The next day an unusually large number of government entities -- eight -- vowed to strengthen measures on such things as project development, home sales and management services, and step up penalties for misconduct. In the line of fire will be developers that default on debt payments, delay deliveries on pre-sold homes or elicit negative news or market concerns.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on the ‘China model’ of governance, the clampdown on tutoring and the technology sector, and the push for more babies.

- Bloomberg News’s Tom Hancock and Bloomberg Economics’s Tom Orlik describe the new order in China as progressive authoritarianism, while Bloomberg Opinion’s Matthew Brooker calls it a market detour to Marxism.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Adam Minter says cheaper weddings may be next.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg