Why Chile’s Presidential Vote Comes at a Crazy Time

Why Chile’s Presidential Vote Comes at a Crazy Time

(Bloomberg) -- Chileans go to the polls on Dec. 19 to choose between presidential candidates from the hard right and the far left. This will be the first election since the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in which the candidates don’t come from the two coalitions that dominated politics in the past three decades; their contenders flopped to fourth and fifth places in first-round voting on Nov. 21. The election comes at a time when the current president (who is barred from seeking a second consecutive term by Chile’s term limits) recently survived impeachment, the fate of the country’s iconic pension system may be at stake and the country’s constitution is in the process of being rewritten. The Chilean peso gained 2.2% on the Monday after the first-round vote before flopping to a new 18-month low.

1. Who are the presidential candidates?

The contenders are Gabriel Boric, a 35-year-old leftist former student leader, and Jose Antonio Kast, a 55-year-old conservative former lawmaker. Boric, who is allied with Chile’s Communist Party, wants to do away with the nation’s market-based neoliberal model. He proposes to raise the minimum wage, as well as corporate and wealth taxes, to cut the maximum work week to 40 hours from 45, introduce workers’ participation in companies’ boards, and to create a new national development bank. Kast’s plan is broadly based on increasing investment incentives. He pledges cutting corporate and wealth taxes and reducing public spending. On social issues, Boric aims to make abortion free and widely available and supports a program of LGBTQ rights to end discrimination. Kast opposes same-sex marriages and abortion, and promises to crack down on illegal immigration.

2. Who’s favored?

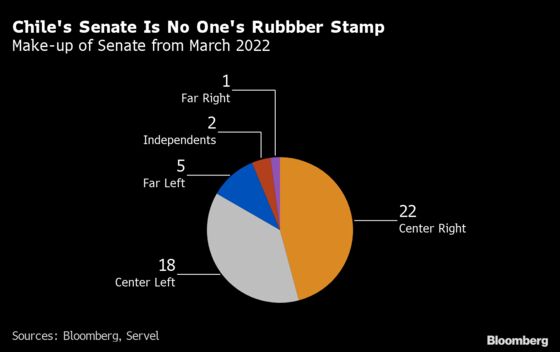

Kast won 27.9% of the valid votes cast in the first-round voting on Nov. 21, to 25.8% for Boric. But as December began, polls were favoring Boric. Whoever gets more than 50% in the head-to-head runoff will assume the presidency in March. That person will also face a congress that’s very divided and will probably need to negotiate to get legislation passed. (Voters in November also chose a new lower house and renewed half the senate.)

3. What’s happening with the current president?

Pinera, a Harvard University-educated conservative who became a billionaire through his work in credit cards and airlines, has been under fire since publication of the so-called Pandora Papers -- leaked documents showing hidden ownership interests of wealthy people around the world. The document alleged that Pinera’s family, in 2010, sold its stake in a $2.5 billion iron-ore project called Dominga to a childhood friend of the president, and that part of the payment was allegedly conditioned on the government not declaring the area a nature reserve. He has denied wrongdoing, saying that his finances were placed in a blind trust at the start of that term, and that he wasn’t informed of the details of the sale. Chile’s lower house voted to impeach him by a vote of 78 to 67 with 3 abstentions. On Nov. 15, Chile’s Senate cleared him after opponents fell short of the two-thirds majority needed to impeach a head of state.

4. Why is the pension system up in the air?

Chile’s system of private, obligatory pension funds -- established in 1981 during Pinochet’s dictatorship to boost savings -- forms the bedrock of the country’s financial markets, since fund managers are the country’s biggest institutional investors. But many Chileans are dissatisfied with the level of retirement payouts. During the pandemic, congress approved a series of early withdrawals from pension funds to support households. So far, Chileans have withdrawn $49 billion. On Dec. 3, the lower house of congress rejected a proposed fourth round of pension withdrawals that could have freed as much as $20 billion more. Boric proposes scrapping the current system in favor of a state-run manager.

5. What’s happening with the constitution?

Following violent protests in 2019 triggered by an increase in the subway fare, Pinera’s government agreed to hold a vote on whether to write a new constitution, long a demand of social activists. (The current constitution, though amended several times since Chile returned to democracy, traces back to 1980, during Pinochet’s repressive rule.) The constituent assembly elected to write the new constitution has to submit a draft for a plebiscite during the first half of 2022. The assembly, largely dominated by leftist groups, could suggest enlarging social and economic rights, as well as changing how the country manages natural resources.

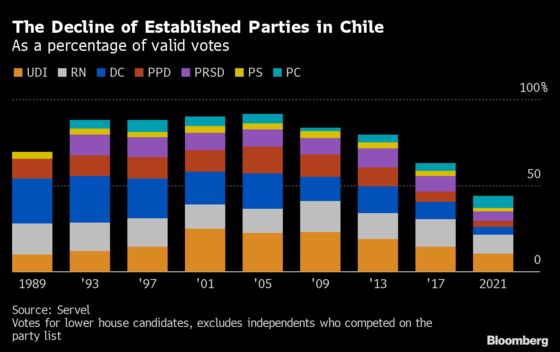

6. What’s behind all the discontent?

Long before the 2019 riots, political scientists had warned of a crisis of legitimacy in Chilean politics. The political system “has drifted away from civil society,” Juan Pablo Luna, an academic at the Catholic University of Chile in Santiago, wrote in 2016. Established parties failed to respond to or channel discontent with rapid economic change characterized by growing wealth and deepening inequality, as well as insufficient provision of pensions, health care and education, often by the private sector.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on Chile’s pension system, the writing of a new constitution and how the country went from an economic star to an angry mess.

- The 2016 paper by Juan Pablo Luna on the country’s “crisis of representation.”

- How rage politics in Chile is threatening a Wall Street haven in Latin America.

- A debate between the country’s main candidates ahead of the first round.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.