What Is the Norway Model, and Can It Solve Brexit?

Why Brexit Is Making a Return Trip to Norway

(Bloomberg) -- With the U.K. Parliament balking at Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit deal, Norway’s arrangement with the European Union is getting another look. It’s a model that might just find broader support -- at least as a temporary move -- until a better answer can be found. Supporters say it’s a lifeboat option that honors the result of the 2016 referendum in which Britons voted to exit the bloc, while minimizing damage to the U.K. economy by ensuring closer ties than May’s plan would. But the route is fraught with obstacles of its own, not least of which is that the EU might not agree.

1. What is the Norway model?

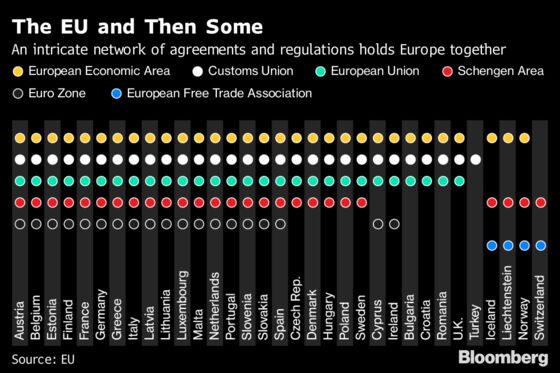

Norway, like Iceland and Liechtenstein, isn’t an EU member but is part of the European Free Trade Association and -- by extension -- the European Economic Area. This gives Norway access to the EU’s lucrative single market for goods and services, which is the destination for more than 40 percent of U.K. exports. Banks based in the EEA have "passporting" rights, which allow services to be offered across the EU with a license granted by the home country. The non-EU nations in the EEA don’t take part in the bloc’s fisheries or agricultural policies.

2. What’s the proposal for the U.K.?

Some lawmakers in both of the main U.K. political parties are championing plans to use the Norwegian arrangement either as a permanent arrangement or as a stop-gap measure while a trade pact with looser ties to the EU is worked out. The model is frequently referred to as “Norway Plus,” implying that the arrangement would be an enhanced version in which the U.K. might also remain in a customs union with the EU.

3. Does the Norway model have a downside?

It does for those who support the U.K. freeing itself from the constraints of the EU. EEA participants still have to accept the EU principle of free movement of labor (i.e. people), which directly conflicts with what many interpret as a main goal of Brexit: to control immigration to the U.K. from the bloc. In addition, Britain would be expected to accept many of the EU’s rules while losing a say in crafting them (Norway has adopted 75 percent of the bloc’s laws in return for accessing the market). Furthermore, the U.K. would have to keep sending money to Brussels, albeit less than the country contributes as an EU member.

4. What is the process and what are the hurdles?

The U.K. would first have to join EFTA, which the country helped to establish almost 60 years ago. That’s because only members of the EU or EFTA can be part of the EEA. Re-joining EFTA would also allow Britain to take advantage of the 29 free-trade agreements the group has with 40 non-EU countries and territories around the world. But a U.K. bid for EFTA entry could run into resistance from the current members -- Switzerland plus EEA participants Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein -- on the grounds Britain’s size would throw the group’s balance out of whack (for example, the group’s future trade deals might become more complex). Beyond that, all EU governments would have to agree to open the EEA to a new participant. That would raise potential further political obstacles, not least when it comes to ensuring EFTA nations’ regulatory standards are aligned with the EU’s.

5. What are the problems that the Norway model resolves?

It respects the political verdict of the Brexit referendum result while limiting the economic shock. In other words, the Norway model removes the U.K. from the EU’s institutions and from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice while keeping goods and services flowing in a frictionless way.

6. Why add a customs union?

The customs union, featuring common tariffs on goods arriving from outside and no duties on products circulating inside, serves a crucial political function in the context of Brexit. That’s because it’s a way to ensure that no border controls re-emerge between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland after the U.K. withdraws from the EU. Preventing such a “hard border” reflects a general deep-seated desire to protect the 1998 peace agreement that ended decades of nationalist-fueled conflict in Northern Ireland. The tricky upshot: continued U.K. membership of the EU customs union would prevent the country from being able to operate an independent trade policy, which is a goal as important to many Brexiteers as is the end of the free movement of people.

7. Why is this gaining supporters now?

With May struggling to win support for her carefully negotiated agreement in the British Parliament, the government and the EU have insisted that the only two alternatives are “no deal,” where the U.K. would crash out of the bloc without any replacement arrangements, or a delay so long that it could kill Brexit altogether. This has alarmed lawmakers who want a close relationship with Brussels that also honors the result of the 2016 referendum. Work and Pensions Secretary Amber Rudd told the Times in December that the Norway model “seems plausible, not just in terms of the country but in terms of where the MPs are.”

The Reference Shelf

- The EFTA website.

- QuickTake Q&As on Europe’s customs union and how Ireland’s border became Brexit’s intractable puzzle.

- QuickTake explainer on why Britain voted to leave the EU.

- More on the differences between the EEA and the EFTA.

- The European Free Trade Association would look a lot different with the U.K. in it.

--With assistance from Simon Kennedy and Robert Hutton.

To contact the reporters on this story: Jonathan Stearns in Brussels at jstearns2@bloomberg.net;Ian Wishart in Brussels at iwishart@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Ben Sills at bsills@bloomberg.net, Leah Harrison Singer, Emma Ross-Thomas

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.