Why Billions in Bonds Now Trade Like ‘Fallen Angels’

Why Billions in Bonds Now Trade Like ‘Fallen Angels’

(Bloomberg) -- Being a fallen angel is not a good thing, whether in the Bible or the bond market. For investors, a fallen angel is a company that has lost its investment-grade debt ratings -- a fall that can have costly consequences. The ranks of that category may be about to get far more crowded, as new economic woes push nearly $1 trillion of debt owed by companies that are currently barely above that level closer to the line. The market has already made up its mind on roughly a third of that, trading the bonds as if they’ve slipped into junk status, even if credit raters haven’t made that call.

1. What makes a fallen angel?

Generally speaking, a fallen angel is a bond that is downgraded to BB+ or below (categories considered junk, or, more politely, high yield) by at least two of the three major rating firms -- Moody’s Investors Services, S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings -- after being formerly rated BBB- or higher (categories that are investment grade). Downgrades can happen when a company isn’t creating enough revenue or generating enough cash to service its debt, or when it takes on so much debt that its financial leverage -- usually calculated by debt as a measure of earnings -- becomes disproportionate.

2. What happens when bonds lose investment-grade status?

A fall to junk status affects both borrowers and investors. For companies, downgrades make borrowing more expensive. A downgrade that extends all the way to junk could mean a need to tack debt covenants to the formal contracts with bondholders. These covenants protect investors who agree to lend to the now-riskier issuer and, often, prevent the company from benefiting shareholders at the expense of bondholders. Junk status also can force a wave of selling by investment companies and funds whose mandates prevent them from holding credits below investment grade. The prices on the bonds may need to fall to compensate investors for holding a less liquid, or actively-traded security.

3. How did we get to this point?

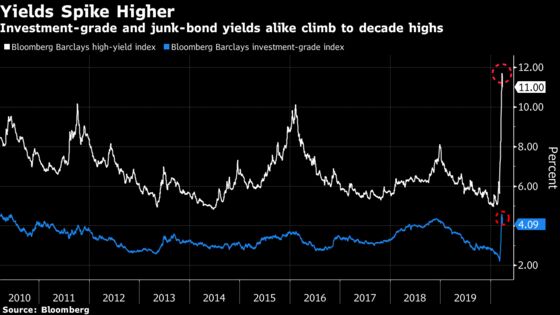

It started with a decade of ballooning corporate debt that followed the 2008 financial crisis, as companies took advantage of record low interest rates. The size of U.S. investment-grade market has more than tripled to $5.7 trillion outstanding since then. Historically low borrowing costs over the last decade paved the way for companies to issue debt and pursue aggressive growth strategies with little consequence. On top of that, leniency by the rating firms allowed companies to maintain investment-grade ratings despite elevated leverage ratios. Investors hungry for higher returns in a low-yield market were willing to lend copiously even as warnings were sounded about the ability of so much debt to be carried through a downturn.

4. What’s happened?

The coronavirus pandemic has made those worries immediate. As companies saw their supply chain disrupted or demand for their products fall or both, earnings projections have been cast into doubt. That’s led traders to start to anticipate downgrades for an ever wider slice of this market.

5. Which companies might be next?

There are some smaller ones that won’t cause much of a market ripple, such as Macy’s Inc. and Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. Then there are some biggies like Ford Motor Co., which already has one high-yield rating, and Occidental Petroleum Corp., one of many BBB energy companies teetering over the edge after a dramatic fall in oil prices. Either would be the largest issuer in the Bloomberg Barclays high-yield index.

6. How many may fall?

That’s not clear. Investors are largely zeroing in on the $868 billion of investment-grade debt that has at least one BBB- or equivalent rating, just one level above junk. Guggenheim Partners said $1 trillion of debt is potentially heading to high yield. As much as $140 billion of investment-grade debt could be downgraded this year, largely given the stress in the energy sector, according to UBS Group AG strategists led by Matthew Mish. At the prospect that lenders may effectively shut many companies out of the credit markets, there’s been a mad dash for cash, with firms increasingly relying on banks and other lenders to fill the gap.

7. Where did the expression ‘fallen angel’ come from?

A 1984 story in American Banker newspaper attributed it to David Solomon, head of Solomon Asset Management, which at the time was a leading investor in the emerging field of junk bonds. (He’s not to be confused with the current head of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.)

The Reference Shelf

- The tipping point for BBBs is closer than ever amid the coronavirus and plunge in oil prices.

- A data visualization of how the BBB universe got to be so large, mainly due to mega mergers and acquisitions.

- An FTSE Russell report, “Fallen Angels in the US credit market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.