Why Argentina, IMF Are Wrestling Over Bad Debt, Again

Why Argentina, IMF Are Wrestling Over Bad Debt, Again

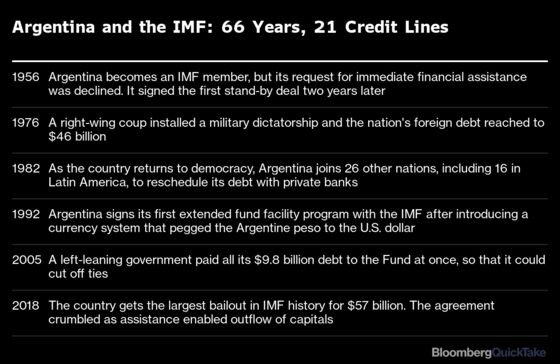

(Bloomberg) -- The fact that Argentina is in talks with the International Monetary Fund for emergency aid to stave off default might not sound surprising -- if agreed, this would be the 22nd IMF loan for South America’s second-largest economy in seven decades. What’s unusual is the size of the IMF package being renegotiated and the complications posed by the pandemic, which hammered an already staggering economy. The conflict this time isn’t just between a left-leaning government that wants more freedom to spend and IMF officials pushing for budget cuts, but between the government and even more liberal members of its own party. That’s kept tension high even after a preliminary deal was struck in late January, as Argentina’s foreign reserves dwindle. The stakes are also significant for the IMF, which has sunk a bigger share of its resources into a single country than ever before.

1. What has Argentina asked for?

The country, home to 45 million people, wants more time to repay over $40 billion owed to the IMF from the last economic aid program in 2018. President Alberto Fernandez asked for an extended fund facility program, or EFF, that would give the country at least a four-and-a-half year grace period before starting to pay back its debt. The IMF has agreed to the idea, and after more than a year of talks, Argentina reached an initial agreement with the Washington-based organization to reduce its fiscal deficit and cut the central bank’s financing of the treasury.

2. What is the initial deal?

Argentina aims to put its budgets on a path to reach what’s called primary fiscal balance by 2025; that would mean a balanced budget if debt interest payments aren’t taken into account. Before that, the country has agreed to reach primary fiscal deficit of 2.5% in 2022, 1.9% in 2023 and 0.9% in 2024 for a new program worth $44.5 billion. While Economy Minister Martin Guzman said the program won’t include labor or pension reforms, the IMF said that cutting energy subsidies will be “essential for improving the composition of government spending.” Argentina spent close to $11 billion in energy subsidies last year.

3. What’s the political issue?

A staff-level agreement, which will set out the explicit targets and commitments that the Fund’s technical staff agree to with Economy Ministry officials, is the next step in talks between the two parts. But Argentina’s Congress has to approve the agreement before the deal reaches the IMF’s executive board, all before a large payment comes due around the end of March. The opposition bloc has a stronger position in both houses after a stinging defeat for the ruling coalition in midterm elections; the lower house in December rejected the government’s 2022 budget proposal. There is also long-standing tension within the government. Lawmaker Maximo Kirchner, the son of powerful Vice President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, resigned as head of ruling party’s lower house bloc in protest over the IMF agreement. “This decision is born from not sharing the strategy utilized, and much less the results obtained, in the negotiations with the IMF, led exclusively by the economic cabinet,” Kirchner, a key voice in the ruling coalition’s far-left wing, wrote in a statement published Jan. 31.

4. How bad is Argentina’s economic situation?

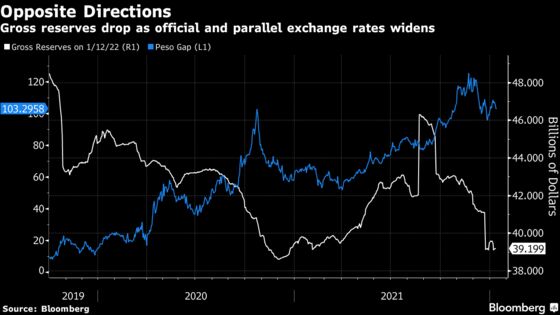

Inflation rose around the globe in 2021 as economies got back in gear after pandemic disruptions. But Argentina’s figure of an annual rate of 51% was the highest of the Group of 20 largest economies. With currency controls still in place, a dollar cost more than 200 pesos on the parallel market, almost double the official rate. Net foreign exchange reserves have fallen close to zero, according to Portfolio Personal Inversiones in Buenos Aires. The country’s liquid reserves, basically what’s available in cash, are negative. Dollars are needed to meet large debt payments, most of all the $2.8 billion due to the IMF in March. Argentina suffered a recession from 2018 into 2021, a downturn worsened by one of the world’s longest lockdowns when the pandemic hit.

5. How did the situation get to this point?

The IMF broke its own credit records in mid-2018 by offering Argentina a $50 billion bailout. It wanted to help a market-friendly government led by Mauricio Macri battle recession in exchange for fiscal austerity and economic reforms. But hardly anything went as planned. Macri’s approval ratings plunged and investors lost confidence in a government that failed to cool down double-digit inflation and control a currency rout. The country asked to receive a larger amount of funding at a faster pace than originally negotiated and within months the credit line was broadened to $57 billion. But Macri lost his bid for a second term in 2019. Fernandez took over as president and asked the Fund to stop further disbursements after $45 billion had been handed over.

6. What does this mean for the IMF?

Argentina’s original deal from 2018 represented more than 10 times the country’s credit allowance with the Fund, and one-third of all the Fund’s outstanding credit. Since making the deal, the IMF has faced a wave of demands for relief from vulnerable countries struggling to cope with the impact of the Covid-19 crisis. From March 2020, the Fund approved $170 billion through emergency financing and credits, according to its website. IMF total outstanding lending reaches $250 billion. A month ago, the IMF published an evaluation of its 2018 deal with Argentina which concluded that the deal had been poorly designed and executed, adding that lack of ownership from the government was “fatal” for the program.

7. What does this mean for investors?

Many of them are still smarting from when Argentina and its largest overseas creditors struck a deal in 2020 to restructure $65 billion of debt after the country defaulted for the ninth time. Bondholders had to settle for 55 cents on the dollar, with capital payments starting in July 2024. Investor sentiment has remained negative as an IMF deal before the March payment deadline has been seen as less likely. Argentina would immediately fall into arrears with the Fund if it doesn’t pay, as the IMF as senior creditor offers no grace period to borrowers. Overseas sovereign dollar bonds were trading in early February at around 30 cents on a dollar. Even if a deal is struck, a plan to postpone debt maturities makes markets wonder if Argentina is just kicking the can down the road.

The Reference Shelf

- Details on the preliminary agreement with the IMF.

- A story on Argentina’s nine sovereign defaults.

- A 2020 QuickTake on how Argentines reacted to capital controls by demanding more dollars.

- The IMF’s page on Argentina.

- IMF’s evaluation of its 2018 stand-by arrangement with Argentina.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.