Who Put the ‘S’ in ‘ESG’ (and What Does It Mean)?

Who Put the ‘S’ in ‘ESG’ (and What Does It Mean)?

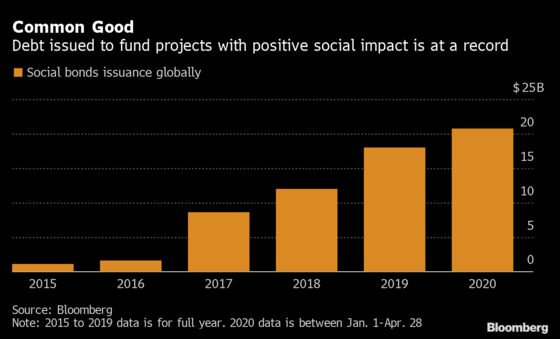

(Bloomberg) -- The three pillars of so-called ESG investing have never been equals. The “E,” for environmental, has dominated the “S” for social and “G” for governance, reflecting concerns about climate change. Now, the coronavirus pandemic has given the S a big boost, with social bonds becoming the fastest-growing part of sustainable finance. Some of those bonds are earmarked for vaccine development or defraying crisis costs. But more broadly, there’s a new focus among investors on how companies treat their workers and how they benefit society. The risk of brand damage for companies seen as engaging in anti-social behavior has also increased.

1. What’s the idea of social investing?

There are many variations, but the common thesis is that capitalism has obligations that go beyond shareholders and return on equity -- investors and companies also need to consider their impact on customers, employees, local communities and society in general. While different strands of the social investing movement may focus on labor standards, LGBTQ rights or corruption, they’re meant to send a common message: Businesses need the consent of people in society to operate, and a threat to this “license” can have an impact on their bottom line.

2. How mainstream is this?

What was once a fringe approach has now seen big investors, including KKR, Vanguard Asset Management and Columbia Threadneedle Investments, create funds focused on social concerns. Such moves aren’t just do-goodism. The claim is that long-term returns will be higher from investing in companies that pay attention to the social part of their business, whether that’s by taking better care of their staff or the environment.

3. This isn’t totally new, is it?

Organized efforts at this kind of investing can be traced back decades, such as Swedish church-affiliated organizations in 1965 and the Pax World Fund, which launched in the U.S. in 1971. Strategies focused on avoiding companies seen as doing specific kinds of harm became known as socially responsible investing. Later, amid increasing scrutiny of their business practices, many companies embraced an approach known as corporate social responsibility. Meanwhile, some money managers advocated what became known as impact investing, which seeks to have a positive influence on the world.

4. How is ESG investing different from all that?

ESG investing has brought these earlier efforts under a single umbrella, at the same time as policy makers and regulators have become increasingly concerned about climate change. That’s brought greater acceptance of those wider ESG concepts, most notably that companies should be held to account for all they do, not just their financial performance. An ESG approach is also typically numbers-based, seeking to score a wide range of information about a firm, from its carbon emissions to safety at work and gender mix in the boardroom.

5. What impact has the pandemic had?

It’s prompted some ESG investors to redirect their efforts from climate toward social issues. A group of more than 300 investors representing over $8.4 trillion in assets recently urged businesses to take steps to protect their workers and communities from the impact of the virus, including providing workers with paid leave and avoiding layoffs. As investors zero in on social, they’ll likely focus in the short-term on what Covid-19 relief companies are providing for communities, consumers and other stakeholders, Kara Mangone, chief operating officer of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s sustainable finance group, said recently. Over the longer term, investors will ask questions about companies’ process and oversight, as well as how the board is engaged on these topics, she said.

6. What companies are getting poor marks?

Facing widespread outrage, Ruth’s Chris Steak House and Shake Shack were among the publicly-traded restaurant chains that returned millions of dollars given out by the U.S. government to sustain small businesses. Large banks also came under criticism for giving priority to larger customers in the handling of requests for government aid, with the effect of shutting out many smaller firms from the first-come, first-served program.

7. What’s happening with social bonds?

Sales of bonds to help fight the outbreak have surged. Alongside a massive increase in government borrowing, and hundreds of billions raised by companies to shore up their balance sheets, development banks such as the World Bank and the Inter American Development Bank have sold tens of billions of debt to tackle the impact of the virus. Proceeds will be used to support the weaker health and economic systems of poorer countries, where it’s feared the pandemic will push more people into extreme poverty and could overwhelm medical facilities. In the corporate market, Pfizer Inc has already sold bonds that’ll help fund greater access to its medicines and vaccines, and other companies and banks are likely to follow.

8. Are those the same as pandemic bonds?

No. Those were issued by the World Bank in recent years based on the model of catastrophe bonds that pay out in response to insurance claims for events like hurricanes. The situation with coronavirus-related borrowing is so new, people haven’t agreed on a single name for these bonds. Most of the securities related to the pandemic aren’t technically social bonds because they don’t follow principles set by the International Capital Markets Association on transparency how the proceeds will be used. Some issuers are using an alternative ICMA template, known as sustainability bonds, where proceeds can be used for green or social purposes, while yet others have invented new labels that don’t follow established guidelines. Asset managers like Nuveen prefer bonds that follow ICMA frameworks as they provide greater accountability. They may also result in cheaper borrowing costs says Herve Duteil, head of sustainable finance at BNP Paribas.

9. How big is the push into social bonds?

Social bonds have been the fastest-growing part of sustainable finance, with more already sold this year than in all of 2019, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Meanwhile, green bond sales have dipped as companies focus on shoring up their balance sheets. Based on industry standards, this is how many people in the market break down the three main types of social bonds:

- Social bonds: All the money raised must be used to promote improved social welfare and positive social impact directly for vulnerable, marginalized, underserved or otherwise excluded or disadvantaged populations

- Social-impact bonds: To fund a particular project with social goals where repayment is linked to whether the project achieved its objectives

- Sustainability bonds: All the money raised will be used for either green or social activities

10. How much is being invested?

Even before the pandemic, impact investing was a fast-growing sector, with over $500 billion in assets globally at the end of 2018, according to the Global Impact Investing Network, though it remains only a fraction of the more than $30 trillion of funds allocated toward ESG strategies. In the U.S., KKR exceeded its $1 billion fundraising goal for its first Global Impact Fund in 2019. A recent Deutsche Bank report suggested “the S in ESG will increasingly be the ‘next big thing’ when it comes to investor focus.”

11. What changes are in the works?

Better data and definitions are two big things that need improvement for the movement to grow. In a survey by BNP Paribas SA, 46% of asset owners and managers found social to be the most difficult sector to analyze. Academics at NYU Stern said in a 2017 study that there were bigger gaps in the data around social than environment or governance issues. Efforts are being made: European authorities have said they aim to follow their classification of sustainable finance with another covering social, though that won’t be for some time. And bodies such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board are seeking to get universal adoption of standardized reporting that would include social elements. Meanwhile, there’s plenty of experimenting with new approaches, such as ETFs that design their holdings in conjunction with charities that in turn receive a cut of the fund’s investment fees.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on green finance and debates over the obligations of capitalism.

- Articles on “social washing,” a new version of “greenwashing” and how the pandemic has focused attention on gig-economy abuses.

- A look at Nuveen’s projections of new social borrowing, and at a rush of pandemic-related bonds.

- A Bloomberg News article on S&P Global Rating’s assessment of the social reputation risks the pandemic poses.

- A report on the scope of impact investing and a panel discussion.

- Amazon.com is facing mounting criticism as activists raise issues about worker rights, antitrust laws and climate change.

- Australia’s economy would be boosted by as much as 8% if the employment gap between men and women narrowed further, according to a report from Goldman Sachs.

- Companies with the highest credit ratings have more women on their boards.

- A report by BNP Paribas SA on “The S in ESG.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.