When Will the Boeing 737 Max Fly Again and More Questions

When Will the Boeing 737 Max Fly Again and More Questions

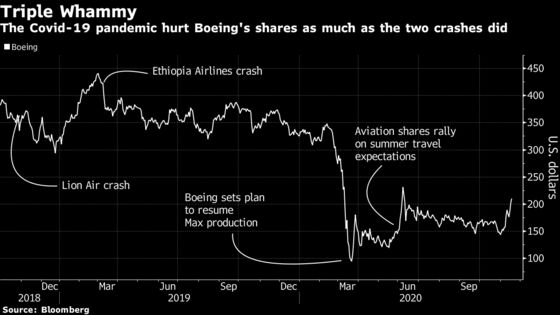

(Bloomberg) -- Two crashes within five months -- Lion Air Flight 610 in October 2018 off the coast of Indonesia and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in March 2019 outside Addis Ababa -- killed 346 people and led to a worldwide flying ban for Boeing Co.’s 737 Max jets, the fourth generation of a venerable brand first flown in 1967. The tragedies and 20-month global grounding battered Boeing’s reputation for safety and transparency, along with its finances. And that was before the pandemic plunged aviation into its worst-ever collapse, leaving Boeing and its best-selling jet to face a long, difficult recovery.

1. When will the 737 Max fly again?

Now that the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration has ended the longest commercial jet grounding in U.S. history, airlines are expected to resume flying the workhorse jet in early 2021, and some may bring back the Max before 2020 ends. After detailed reviews and scores of test flights, including one with FAA chief Stephen Dickson at the controls, regulators determined the company safely redesigned flight-control software linked to the crashes. The agency also signed off on new pilot training courses that Boeing developed in a stunning reversal of the company’s earlier campaign to minimize training.

2. What about outside the U.S.?

Europe is following the lead of the U.S., and Canada and Brazil are expected to as well. China, the first country to ground the jet, hasn’t given a clear timetable for its return.

3. Will air travelers get back on board?

That remains to be seen. The tragedies sparked global fury at Boeing and its “death jet,” as British tabloids dubbed the 737 Max. And consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who lost a grandniece in the Ethiopian crash, continues to stoke safety concerns. In the aftermath of the grounding, 20% of U.S. travelers said they would definitely avoid the plane when it returned. But many consumers had already moved on by the time the Covid-19 pandemic shut down travel, Google Trends data show. While many passengers can’t tell a Boeing from an Airbus SE jet, United Airlines, for one, plans to give its customers plenty of warning that they’ll be flying on a Max via its app or website. That way nervous passengers can switch their travel plans, if they prefer.

4. How many 737 Maxes are out there?

Before the crashes, Boeing reported 387 deliveries to 48 airlines or leasing companies, with orders from around 80 operators for 4,406 more. Chinese airlines account for about 20% of 737 Max deliveries globally, most of them the Max 8, the model involved in both crashes. (The lineup, from smallest to biggest, also includes Max 7, 9 and 10.) Boeing kept its 737 factory in Renton, Washington running at high speed for months after the grounding, believing that regulators would quickly approve the company’s proposed software fixes. More than 450 of the jets eventually wound up in storage before Boeing finally tapped the brakes on production.

5. What has this meant for the aviation industry?

Airlines fumed over groundings that forced them to cancel hundreds of daily flights, and later looked to cash in on the disruption. Once an aircraft’s delivery has been delayed for 12 months, customers typically have the contractual right to cancel it without penalty. Airlines and lessors took advantage of those terms, either scrapping or threatening to bolt from more than 1,040 Max orders. Rival Airbus hasn’t experienced the same turmoil and is poised to expand its lead of the single-aisle market.

6. What has this meant for Boeing?

The crashes cost Boeing the title of world’s largest planemaker and badly tarnished the century-old company’s reputation. The estimated bill for the crashes is at least $20 billion and could ultimately be far larger when lost sales are taken into account. The company faces long-lasting repercussions from former Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg’s decision to keep churning out 737s during the grounding. It will take at least through 2023 to clear those never-delivered Max out of storage, hampering Boeing’s financial recovery. About one-quarter of those planes have lost their original buyers, leaving the company searching for new takers -- more than likely by offering hefty discounts. Muilenburg was ousted for his handling of the crisis. Other senior executives to depart during the crisis included Kevin McAllister, the head of Boeing’s jetliner division; Anne Toulouse, its communications chief, and J. Michael Luttig, a former general counsel who spearheaded the company’s legal response to the accidents.

7. What legal action does Boeing face?

Relatives of crash victims filed claims, and most of the Lion Air families have already settled with Boeing. Shareholders, Boeing employees and pilots also sued for damages with varying degrees of success. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates Boeing’s litigation risks in the U.S. could amount to $2 billion. Boeing separately offered $100 million over several years as an “initial outreach” to support the families of victims and others affected, and hired high-profile mediator Kenneth Feinberg to distribute it. On other legal fronts, the U.S. Justice Department expanded its probe to include a look into manufacturing of another Boeing aircraft -- the 787 Dreamliner -- at a new plant in South Carolina. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating whether Boeing properly disclosed issues tied to the 737 Max jetliners to investors.

8. What do people think caused the crashes?

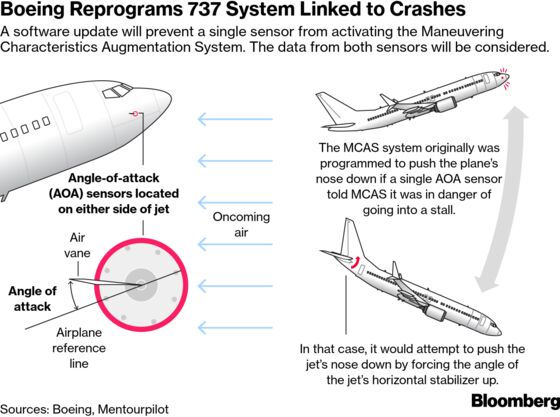

Indonesian investigators blamed a flight control system that repeatedly dove the plane during a malfunction, as well as errors by the pilots and maintenance failures. The Ethiopian investigation isn’t complete, but the same system -- known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS -- also kicked on due to an erroneous sensor reading and pushed the plane’s nose downward repeatedly until pilots lost control. After Boeing added new engines on the 737 Max, the plane had a tendency to nose-up in rare conditions and MCAS was designed to counter that automatically. Reports by crash investigators as well as U.S. lawmakers and watchdog agencies have all said, to varying degrees, that Boeing didn’t anticipate how confusing such a failure could be for pilots. A relatively simple procedure could have saved both flights, but neither flight crew was able to execute it properly. The reports have also criticized the lack of redundancy in the design that allowed a single sensor to trigger such a failure.

9. Who approved this system?

The FAA gave final certification to the 737 Max in March 2017, and it entered commercial service two months later with Lion Air. Under a long-standing program that was expanded in 2005, the FAA had delegated to Boeing the authority to perform some safety-certification work on its behalf. The program has been controversial and some FAA employees say it gives Boeing too much sway over safety approvals of new aircraft, but it was expanded several times by U.S. Congress. Federal regulators signed off on the initial design of MCAS. But as Boeing honed and tested its Max designs over several years, it gave MCAS more authority to push down the jet’s nose. The company’s own engineers signed off on those changes and didn’t fully explain them to FAA engineers, a Transportation Department Inspector General later determined. A Boeing pilot boasted of using “Jedi mind tricks” to sway FAA examiners and complained the Max was “designed by clowns, who in turn are supervised by monkeys.”

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on MCAS and lawsuits in the U.S. from the Lion Air crash.

- Indonesia’s crash report included a partial transcript from the cockpit of the final minutes of the Lion Air flight.

- Why Boeing’s profit push may have left Max pilots unprepared.

- A fight for survival on the Ethiopian jet came down to two cockpit wheels.

- A look at the “damning” emails that left Boeing’s integrity in tatters.

- Flawed analysis, failed oversight: The Seattle Times.

- Boeing’s 737 Max page.

- How an off-duty pilot saved a doomed Max jet on its second-to-last flight.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.