What to Know About Biden’s Plans for U.S. Child Care

What to Know About Biden’s Plans for U.S. Child Care

(Bloomberg) -- Around the globe, remote schooling and closed day-care centers during the pandemic forced parents to make painful tradeoffs between work and family. Women bore the brunt, abandoning the workforce in greater numbers than men, with little control over when they could return. In this, the pandemic greatly exacerbated child-care predicaments in many countries, including the U.S., where Covid-19’s economic fallout has been called the first “female recession.” Some governments are getting more involved in child care as a result, with U.S. President Joe Biden hoping to join their ranks.

1. What did the pandemic do?

It cost women at least $800 billion in lost income in 2020, according to the antipoverty group Oxfam International, which also estimated that job losses reached 5% among women, compared with 3.9% among men. Not all of that can be blamed on child-care issues, of course: Around the world, women are overrepresented in retail, tourism and food services, which were particularly hard-hit by shutdowns. In the U.S., more than 4 million women dropped out of the labor force at the height of the pandemic, many to become caregivers, and 1.5 million remained on the sidelines as of November.

2. Why is the problem so pronounced in the U.S.?

Unlike many rich nations, the U.S. doesn’t guarantee child-care assistance for working parents. In other wealthy countries, support for the care of children begins with a guarantee of significant paid parental leave after a baby’s birth — at least six months’ worth in Canada, Italy, Germany, Japan and South Korea as of 2016, with Estonia leading the pack at 85 weeks, according to a study by Unicef. The U.S., starting in 1993, guaranteed 12 weeks of leave, but it’s unpaid and only for employees of companies with at least 50 workers. Elsewhere, policies support working parents when kids are older, too. England makes 570 free hours of child care available each year for all 3- and 4-year-olds. Child care in Sweden and Denmark is heavily subsidized.

3. How does child care work in the U.S.?

It’s a patchwork system of commercial facilities, home-based providers and nannies, plus the grandparents, neighbors and friends who fill in the gaps. Families handle the burden mostly on their own, with only low-income working families qualifying for government subsidies. The cost of infant care, the most expensive type, exceeds 20% of the median household income in 21 states. More than half of Americans, especially in low-income and rural areas, live in “child-care deserts,” where demand far exceeds supply.

4. What explains the shortage?

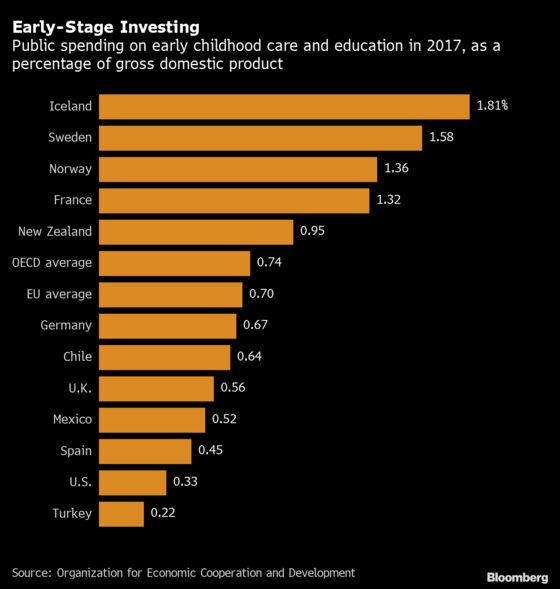

Incentives to enter the field are low. Caregivers, mostly women and disproportionately women of color, earn $12.12 an hour on average for watching children younger than 5 — wages so low that about half of them rely on public assistance, according to the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California at Berkeley. Many reasons are given for the low wages in the face of high demand for child care. One big one is that looking after young children comes with a litany of regulations to ensure the programs are safe, the priciest of which is a child-to-staff ratio requiring one caregiver for every three or four infants, depending on the state. The sector gets little support from the U.S. government, which spends just over 0.3% of gross domestic product on early childhood education and care, compared with more than 0.7% on average among the 38 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. And most of the U.S. spending is for public kindergarten, which starts at age 5. For care of children younger than that, the U.S. spends less than 0.2% of GDP, according to a 2020 study by the Economic Policy Institute, a think tank.

5. What steps did countries take during the pandemic?

Some were forced to address broken child-care systems, at least temporarily. Australia’s center-right government, in April 2020, made child care free to all for about three months, and by that September, women’s labor force participation had rebounded more strongly than that for men. Canada’s government is working to implement a nationwide, subsidized child-care plan that was first proposed almost two decades ago. The Japanese government gave cash handouts to lower-income households with children and aims to get the number of preschool children who can’t secure a spot in a care facility to zero.

6. And in the U.S.?

An economic stimulus measure enacted in March 2021 appropriated $25 billion to help child-care providers cover operating expenses, cleaning and virus-related supplies. Part of Biden’s Build Back Better social spending proposal, being debated in Congress, would appropriate hundreds of billions of dollars more to partially subsidize the cost of child care for low-income families, make government-funded preschool available to all 3- and 4-year-olds and lock in a $300-per-child monthly increase in a tax credit for working parents that was raised temporarily during the pandemic. Biden has also urged Congress to raise the national minimum wage to $15 for all workers, from $7.25 currently.

7. What’s the case against Biden’s proposal?

That it’s an example of government trying to intervene where it shouldn’t. Republican Senator John Barrasso of Wyoming said Biden is pressing for “a cradle-to-grave role” for government.

8. Would the U.S. ever nationalize child care?

Congress actually tried that in 1971, passing legislation to create a national network of federally funded child-care centers in response to the large number of mothers entering the workforce. President Richard Nixon vetoed the bill.

9. What impact does child care have on the U.S. economy?

Even before the pandemic, prime-age women -- those 25 to 54 years old -- participated in the U.S. workforce at a much lower rate than men. The gap widened after Covid-19 shut many day-care centers and schools. Fewer women working weighs on overall productivity. Even a modest increase in labor force participation by women could add $511 billion to gross domestic product over the next decade, according to an October 2020 study by S&P Global. The White House estimates that roughly 1 million parents, primarily mothers, would enter the labor force if child care is made more affordable and accessible.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Businessweek on how child care became the most broken business in America.

- The Biden White House summary of its American Families Plan.

- The S&P Global study, “Women at Work: The Key to Global Growth.”

- A Cato Institute commentary on why families, rather than the government, should make decisions on child care.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.