What Made U.S. Health Care So Vulnerable to Covid-19

What Made U.S. Health Care So Vulnerable to Covid-19: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- America’s health-care system, the most expensive in the world, is under renewed scrutiny because of the coronavirus pandemic. U.S. employers and households spend almost $4 trillion annually on medical care, yet America regularly lags its peers in key health metrics, and it registered the greatest number of confirmed coronavirus cases and deaths anywhere in the first six months of the global crisis. In advance of a presidential election in November, the virus’s assault shined a spotlight on the gaps and inequities in the market-driven approach of the only rich country not to have universal health care.

1. How is U.S. health care different?

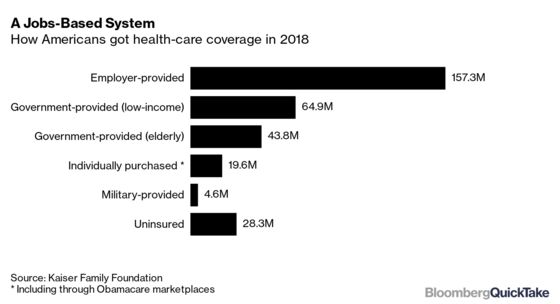

Government involvement in health care goes against the libertarian streak that distinguishes the U.S. from, say, the U.K. and Canada, whose state-funded health systems guaranteeing care for all are derided by some Americans as “socialized medicine.” Only about 36% of Americans, mainly the elderly and poor, receive health-care coverage through the government, via the Medicare and Medicaid programs. More than half of Americans have health insurance as a benefit through work (and can lose coverage if laid off). The 2010 Affordable Care Act, more commonly called Obamacare, has helped about 20 million Americans get health coverage by expanding access to Medicaid and subsidizing purchases of individual plans. Still, as of 2018, about 9% of the population, or 28.3 million people, had no health insurance.

2. What do the uninsured do?

About 1-in-4 put off seeking care in 2018 because of the expense, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. When emergencies arise, those lacking insurance often seek treatment at hospitals, which by law can’t turn them away. Even among those with insurance, about 29% were “underinsured” in 2018, meaning they faced high out-of-pocket costs when seeking care, according to the Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation. Those costs can total about $650 a year on average for the non-elderly and can reach into many thousands of dollars in the event of a “surprise billing,” when a patient receives care, often in an emergency, from a provider that’s not covered by the patient’s insurer. Medical expenses or health-related income loss resulted in an average of 530,000 bankruptcies each year in the U.S. from 2013 to 2016, according to the American Public Health Association.

3. What happened when the virus hit?

America’s patchwork system created confusion, muddling the response. Since prices are unregulated, concerns about out-of-pocket costs for coronavirus tests lingered even after federal officials assured Americans they’d pay nothing. The federal government also promised to pay the hospital bills of uninsured Covid-19 patients, and major insurers eventually pledged to waive out-of-pocket hospital expenses for their customers, but concerns about unexpected bills remained. The virus took a particularly harsh toll on Black Americans, who, as a result of income inequality and disparities in access to health care, are more likely to have underlying conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and lung disease. Some state governors bemoaned the lack of a coordinated federal response to challenges such as ensuring sufficient supplies of tests, ventilators and personal protective equipment for health-care workers, tasks that were left to underfunded statelevel public-health departments. The U.S. spent 17% of gross domestic product on health care in 2019, double the average of the well-to-do members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But it allots only 3 cents out of every dollar to public health, the field devoted to protecting entire populations by, among other things, responding to infectious disease.

4. Where does U.S. health spending go?

The system encourages more expensive, specialized treatment over primary care. This does make the U.S. a leader in many aspects of medicine. It’s long been at the forefront of research and has lower death rates for breast cancer, heart attacks and strokes. Patients face shorter wait times to see specialists and can have access to state-of-the-art procedures. U.S. doctors earn roughly twice as much as those in other wealthy countries. At the same time, the U.S. has some of the worst health outcomes, including the lowest life expectancy among its peers and the highest rate of “avoidable deaths” -- those that could have been prevented with effective care.

5. How is health care an election issue?

President Donald Trump and the Republican Party generally regard Obamacare as government overreach and support a challenge before the Supreme Court that could gut it. Some Democrats want to abolish the existing system of private insurance in favor of a government program along the lines of the U.K.’s. Trump’s presumptive Democratic challenger, former Vice President Joe Biden, doesn’t go that far but does want to lower the age for Medicare eligibility to 60 from 65 and create a government-provided health plan -- a “public option” -- that Americans could buy into.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on surprise billing, what’s left of Obamacare and what’s meant by “Medicare for all.”

- These charts show the disproportionate effect of Covid-19 in majority-Black counties.

- How U.S. health care puts $4 trillion in all the wrong places.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.