What Is Womenomics, and Is It Working for Japan?

What Is Womenomics, and Is It Working for Japan?

(Bloomberg) -- Prime Minister Shinzo Abe thinks he’s found an answer to Japan’s shrinking workforce: The vast ranks of women who’ve been excluded from or held back in the workforce. Abe has outlined goals to create a “Japan in which women shine.” He’s pushing policies to encourage and enable women to work and have a family at the same. There’s even a catchy phrase, "womenomics," part of the prime minister’s broader Abenomics plan hatched in 2014 to lift Japan out of decades of economic stagnation. But while womenomics has seen some progress, it has yet to sparkle.

1. What exactly is womenomics?

It’s the idea, closely associated with Abe but also discussed around the world, that the advancement of women and economic development are necessarily linked. In Japan, as well as getting more women to work, Abe wants them to fill 30 percent of leadership positions by 2020. He’s working to fix daycare shortages and encouraging workplaces to be more accommodating, so mothers will feel more inclined to rejoin the workforce. There’s some urgency: Japan has the world’s oldest and most rapidly shrinking population, with the 15-64 age group forecast to fall to 45 million people in 2065 from 77 million in 2015.

2. Is it working?

It’s slow progress. Female labor participation rate rose from 46.2 percent in 2012 to just short of 50 percent percent in 2017. (That compares with 55 percent in Germany, 56 percent in the U.S. and 61 percent in Canada.) Yet most new women workers in Japan are in relatively low paid, part-time jobs. Although companies such as Toyota Motor Corp. are appointing female executives, change has been glacial and far from uniform across industries. Only 4 percent of managerial positions are held by women (up from 1 percent in 2012) compared with 9 percent in China and 17 percent in the U.S.

3. What’s the issue?

An expectation that women should stay at home and be primary caregivers has held them back in workplaces the world over, but in Japan that view has been deep-rooted. In many cases, women are trying to infiltrate an environment that’s built around working long days often followed by bonding drinks in the evening. A 2016 poll found that 45 percent of men surveyed agreed with the idea that “women should stay at home.” Attitudes were recently highlighted when it emerged that a medical school in Tokyo systematically excluded female students in favor of less qualified men. The furor prompted a national inquiry into admissions at medical schools.

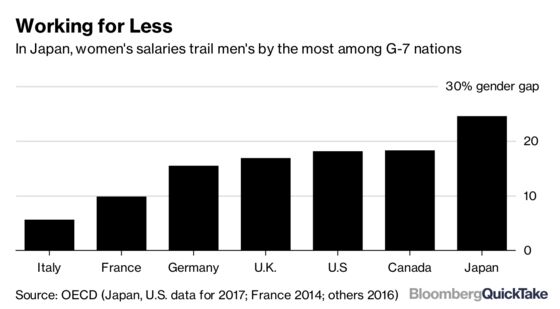

4. What about pay?

Japan has the third-highest gender pay gap among the 36 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, with women paid 24.5 percent less than men last year, down from 26.6 percent in 2013. South Korea has the highest (34.6 percent) while Luxembourg’s is lowest (3.4 percent).

5. How about in politics?

Japan has almost the lowest female representation anywhere. Ten percent of members of the lower house are women, ranking Japan 158th globally. Of 20 positions in the cabinet, two are women. In May, both houses of parliament unanimously passed a bill requiring political parties to aim "as far as possible" to field equal numbers of male and female candidates.

6. What else can be done?

Abe has been criticized for not going far enough and he has shown little indication of a course correction. There have been calls for legally binding quotas to speed along a process that most observers expect to be long but ultimately fruitful. Recent estimates suggest that improving economic gender parity could add $550 billion to Japan’s gross domestic product.

The Reference Shelf

- Japan’s unforgiving work culture.

- When 100 percent equals 80 percent: The medical school scandal.

- A QuickTake on shrinking Japan.

- Cracking Japan’s glass ceiling.

- A Goldman Sachs report on womenomics.

- Japan’s turns #MeToo into #WeToo.

To contact the reporters on this story: Shoko Oda in Tokyo at soda13@bloomberg.net;Isabel Reynolds in Tokyo at ireynolds1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.