What Is Hong Kong’s ‘Northern Metropolis’ Plan About?

What Is Hong Kong’s ‘Northern Metropolis’ Plan About?

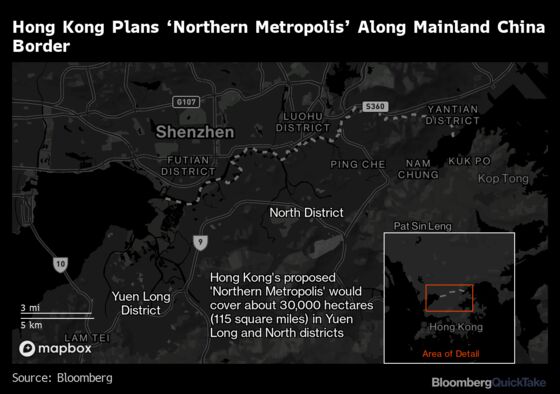

(Bloomberg) -- In early October, Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, unveiled an ambitious plan to transform remote districts bordering the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen into a “Northern Metropolis.” The long-term project aims to alleviate the city’s chronic housing shortage and foster a new high-tech hub. How long it will take and at what cost remain to be seen, but it’s already sent yet another signal that the former British colony sees closer integration with the mainland as its future.

1. What’s the idea?

To wrap the development of two districts at the top of the New Territories -- one of the city’s three main regions, along with Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon peninsula -- into a single, “vibrant” Northern Metropolis. The districts, Yuen Long and North District, have 27% of Hong Kong’s total area, but only 1 million of its 7.5 million residents. The plan is to raise that to 2.5 million residents over about 20 years, attracting people from more-crowded parts of a city that is often cited as the world’s least affordable housing market. It will also be home to an “international innovation and technology hub,” in what’s seen as another bid by the Hong Kong government to create a rival to Silicon Valley.

2. What’s the location like?

It’s about 40 minutes to an hour by rail from Hong Kong’s Central business district. There are centuries-old walled villages and high-rise public housing as well as rolling mountain peaks, parks and wetlands that draw a steady stream of hikers and nature lovers. There’s also an abundance of vacant land, farms and brownfields that have long been seen as a great opportunity for development.

3. Why is she proposing it now?

Lam has faced growing pressure from China to address Hong Kong’s housing shortage, which Beijing blames for the discontent that led to widespread anti-government, pro-democracy protests in 2019. But she said in an interview with Bloomberg Television that the idea was formulated in Hong Kong, and that she showed it to mainland officials only a couple of days before its release. The pro-establishment Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong party had been advocating for a strategic-development plan for the north in recent months.

4. What are the hurdles?

- To claim land for public housing development, the government has to tackle the interests of land owners, from villagers to property developers. Owners have the right to challenge the government in court if they find its proposed appropriation of their land unfair. This could lead to yearslong legal disputes.

- The government has to build a comprehensive transportation system in these relatively inaccessible districts. On top of new rail stations, there is a need for other urban infrastructure including highways and drainage systems.

- Money. Lam said the government hadn’t yet calculated what the plan would cost. But transforming almost one-third of Hong Kong’s territory is sure to put pressure on the government’s finances as the city recovers from two years of recession.

- The border? Hong Kong’s economy still operates autonomously from the mainland, with different rules, regulations, even currencies. Driving from Hong Kong to Shenzhen requires special permits as well as a mainland driving license. Foreigners have to apply for an additional visa to enter the mainland. Even though the Hong Kong government is looking to facilitate border-crossing, it’s unlikely to be anywhere near as simple as, for example, crossing the San Francisco Bay.

5. Who’s the target audience?

For now, the Chinese government it seems. The plan sends a message that the Hong Kong administration has the vision and determination to address the housing crisis. Its emphasis on integration with Shenzhen, China’s tech hub, also fits into Chinese President Xi Jinping’s agenda for knitting the cities along with Macau, Guangzhou and others into a regional powerhouse dubbed the Greater Bay Area. For regular Hong Kong residents, however, it doesn’t mean much, since it would take a long time to see any material impact.

6. Hasn’t this been tried before?

It indeed isn’t a novel idea to expand into the New Territories. The British colonial government started building satellite towns in the 1970s close to Kowloon to accommodate a booming population. These towns later become well-integrated residential areas with convenient transportation. What’s different with Lam’s vision is the technological element aimed at capturing opportunities from Shenzhen, home to such giants as Tencent Holdings Ltd., BYD Co. and Huawei Technologies Co. (The site would be just a railway link away from an artificial island being built as Tencent’s future headquarters.) Hong Kong’s previous attempt at a tech hub -- the Cyberport incubator that started on Hong Kong Island almost two decades ago -- has produced only one major success, the logistics firm GoGoVan Ltd.

7. How will it affect property prices?

It is unlikely to make a dent for now. Without short-term measures to cool property prices like raising taxes, home prices are set to increase even more. There are already anecdotes of homeowners in the proposed Northern Metropolis area asking for higher prices when putting their apartments up for sale.

The Reference Shelf

- More QuickTakes on China’s increasing grip on Hong Kong, how it’s changed the way elections are run, and who is and isn’t leaving.

- Full transcript of Carrie Lam’s October policy address.

- The government’s fact sheet about urban development in the New Territories.

- Bloomberg Intelligence reports on Hong Kong’s housing policy shift.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Matthew Brooker examines what it all means for the city’s property tycoons.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.