What a Liquidity Trap Is and Why We’re Looking at One

What a Liquidity Trap Is and Why We’re Looking at One

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve is doing everything it can to keep the U.S. economy from crashing during the shutdown to fight the Covid-19 pandemic. But some people fear that the Fed has fallen into a “liquidity trap.” That’s a situation in which the central bank’s efforts to stimulate spending fail because people hoard cash instead.

1. What’s liquidity?

“Liquid” means easy to spend, like cash. Bonds aren’t as liquid, but they earn interest. So in ordinary times, people keep some money in cash for spending and some money in bonds for investing. But when the interest rate on bonds falls to zero, people might as well keep all their money in cash.

2. What is a liquidity trap?

The notion goes back to British economist John Maynard Keynes in his path-breaking 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, and to Keynes’s interpreter, John Hicks. The liquidity trap is the inability of a central bank to stimulate economic growth through interest rate cuts. The goal is to stimulate spending by making borrowing cheaper and saving less attractive. The trap opens up when the public’s demand for goods and services is so weak that even an interest rate of zero fails to juice activity. In theory, a bank could have a bigger impact by cutting rates below zero – paying people and businesses to borrow. In practice, negative rates have turned out to be more complicated.

3. Why is that?

Because savers won’t tolerate them. If the interest rate paid on savings goes negative, it means that your money will shrink if you leave it in a savings account. The goal of negative rates is to spur you to spend the money now, which would be good for economic growth. But it also might cause you to take your money out of the bank and put it under a mattress or in a safe. Banks can’t operate if they lose all their deposits. Some key rates in Europe and Japan are below zero, but only slightly. In the U.S., the law that created the Federal Reserve may not allow the Fed to lower rates below zero, according to some interpretations, and Fed officials have said they’re not interested in the idea.

4. How low are rates now?

Rock bottom. In the U.S. the target range for the federal funds rate, which is the interest that banks charge each other for overnight loans of reserves, was 2.25% to 2.5% in July 2019 when the Federal Reserve began reducing it. To fight the effects of the coronavirus shutdown, the Fed cut the target range by 1.5 percentage points in two emergency meetings in March alone, bringing it back to its floor of zero to 0.25%.

5. What’s dangerous about a liquidity trap?

If low interest rates can’t stimulate people to spend enough to keep the workforce at full employment, the risk is that a liquidity trap will set off a deflationary spiral in which prices fall, causing people to delay spending, which makes prices fall even more, and so on down.

6. So is the U.S. stuck in a liquidity trap?

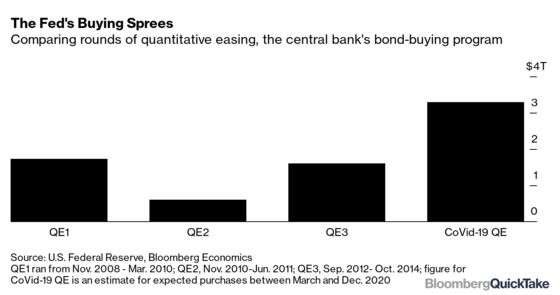

Not necessarily. The Federal Reserve has other ways of stimulating the economy, and it’s using all of them. It’s buying long-term bonds in order to lower long-term interest rates, the program known as quantitative easing. It’s steering market expectations with forward guidance, which is essentially a promise to keep rates low for a long time, even if that causes a jump in inflation. The Fed went even further in March 2020, announcing plans to provide direct support to U.S. employers, municipalities and households, which would traditionally be viewed as fiscal policy.

7. Will that plan work?

Not alone. Congress will need to add stimulus by spending more or cutting taxes. That’s called fiscal policy. Fortunately, while monetary policy becomes less effective in a liquidity trap, fiscal policy becomes more effective. Interest rates don’t go up when the government spends more, so the new spending doesn’t “crowd out” private investment. It’s a pure plus for growth. It won’t prevent a recession, but combined with the Fed’s aggressive actions, it should shorten the length of time the economy is stuck in a liquidity trap.

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake on Japanification and secular stagnation.

- A QuickTake on negative interest rates.

- What Else Can Central Banks Do? a 2016 report by the International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies in Geneva.

- It’s Baaack, Twenty Years Later, a 2018 update by Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman of his seminal 1998 paper warning of the risk of a liquidity trap.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.