Unraveling the Mysteries of China’s Multiple Budgets

Unraveling the Mysteries of China’s Multiple Budgets

(Bloomberg) --

China’s fiscal policy is bewildering. Consider this: four different budgets collectively cover all government revenue and expenditure, but the official deficit -- the main indicator of fiscal policy -- is calculated using only one of them. A considerable part of spending is in the shadows, and some argue the government hides the true size of the deficit. In addition, a lot of liabilities that are ultimately the state’s responsibility aren’t counted on its balance sheet, but on those associated with local governments. That obscures the extent of the national debt -- a key source of stimulus spending employed to respond to shocks such as the coronavirus pandemic.

1. How big is China’s budget?

According to the main one, China’s government spent about 23.5 trillion yuan ($3.4 trillion) in 2019. That compares with an estimated U.S. federal budget of $4.6 trillion in 2020 -- not including any recent measures to deal with the coronavirus. As a share of the economy, the Chinese budget is about 23%, slightly more than its American counterpart. But China’s doesn’t include a range of important funding sources or almost 40% of spending, such as money from land sales and special debt sales. Once you include all the other money, total expenditure was actually 37.2 trillion yuan.

| 2019 Budgets (in trillions of yuan) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Spending | Deficit | |

| General public budget (as announced)* | 20.76 | 23.52 | 2.76 |

| Government fund budget* | 9.98 | 9.98 | 0 |

| Savings from previous years in general public budget | 0 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Savings from previous years in government fund budget | 0 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Special bond budget | 0 | 2.15 | 2.15 |

| Total | 30.74 | 37.18 | 6.44 |

| *Includes provincial and national budgets; savings from previous years also included in income column but separated out in spending column. | |||

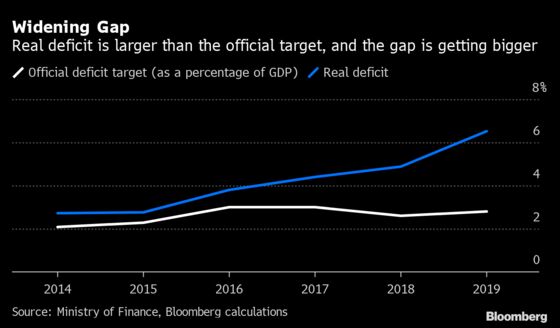

2. How big is the deficit?

Looking at just the general public budget, as the official economic plans do each year, the government planned a 2.76 trillion yuan deficit in 2019, or 2.8% of gross domestic product. Once you include all the other spending listed in the table above, the deficit is 6.5% of GDP, according to Bloomberg calculations. By international standards, that’s a big deficit.

The Chinese government also has a budget for state asset management and another for social security insurance. Since the revenue and expenditure in those two are generally used in dedicated sectors and are much smaller than the main budgets, economists don’t count them as part of China’s broad fiscal picture.

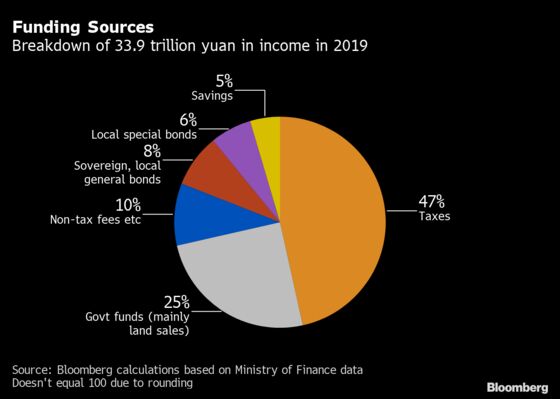

3. Where does the money come from?

Much of the government’s tax revenue comes from companies, and the 2 trillion yuan tax cut last year meant that didn’t grow much in 2019. The authorities claim the tax cut boosted economic growth by about 0.8 percentage point. Tax revenue rose 1% in 2019, down from an 8.3% increase in 2018. This chart below shows actual revenue at the end of 2019, whereas the table above shows the expected revenue in the budget early in the year.

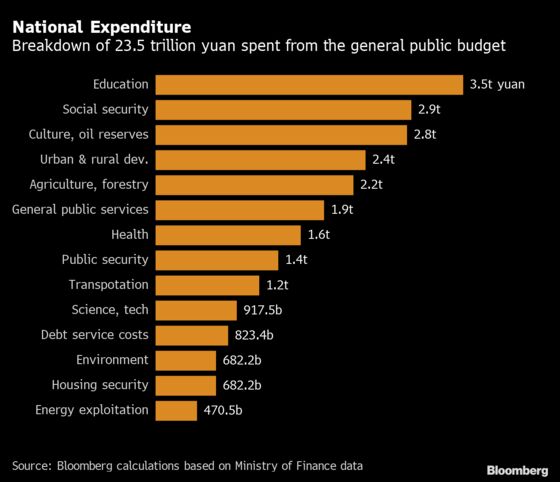

4. How is it spent?

Hard to say. The biggest expenditure category in the general public budget is education, followed by social welfare. But the finance ministry doesn’t release details. Bloomberg has calculated the chart below based on a general breakdown from the ministry, but it’s unknown how this money is actually spent or which department spends it. For example, the government earmarked 1.2 trillion yuan for defense in 2019, according to an announcement early that year, but there is no specific line item for defense in the official spending breakdown. (That gets released about a year later.) Compared with the average among rich countries, China appears to spend more of its budget on education, for instance, but much less on health care.

5. What about the other budgets?

Outside the main budget, big-ticket expenditures include costs related to infrastructure - demolishing old buildings, relocating residents and preparing land for development projects. While China’s government is seen as a big investor there, it’s again difficult to estimate how much is spent due to the lack of detail. In the main budget, funding for infrastructure is scattered among different programs such as urban and rural development or the construction of affordable housing. In the other three budgets in 2019, 2.15 trillion yuan of special debt is in theory meant to finance new infrastructure, although some economists calculate that only a small part of it was actually used directly for construction. The budget for state assets also include some additional, related spending. Spending to pay interest on debt has risen to about 834 billion yuan in the main 2019 budget from about 500 billion yuan in 2016. However, not all government liabilities are included in that budget.

6. How does China use fiscal policy to boost the economy?

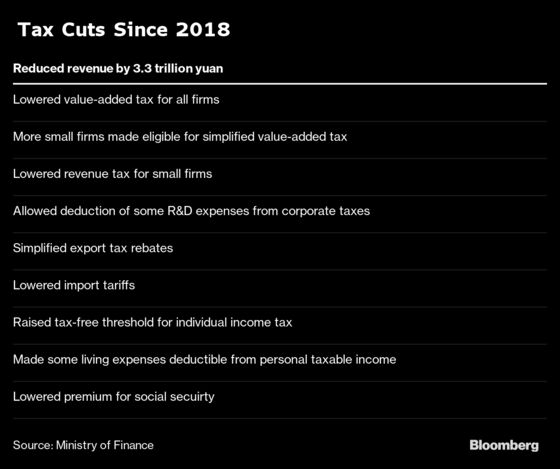

Over the past few years, the government has been trying to use fiscal policy to support the economy more than massive monetary stimulus of the sort deployed during the global financial crisis, out of concern over financial stability and high debt levels. Now, in the aftermath of the coronavirus outbreak, investors have called for large-scale fiscal stimulus.

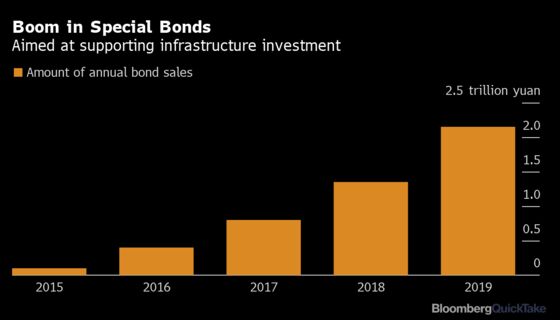

While the government hasn’t detailed its plans, it has pledged to increase the amount of special debt to raise funding for infrastructure investment. Local authorities started selling so-called “special bonds” in 2015 to finance infrastructure projects. The money raised and the debt sold isn’t included in their official deficits. But it does show up on the government fund budget, and hence is part of explicit government liabilities. The quota for these sales has risen each year, and economists forecast at least 3 trillion yuan worth for 2020.

A problem of any fiscal stimulus in China is a lack of funding sources. Special bonds alone -- be it 3 trillion yuan or even higher -- are not enough compared to about 20 trillion yuan of entire infrastructure investment that economists estimate for 2020. While a considerable part of it isn’t new investment, there’s still a gap to fill. In the past, off-balance-sheet financing, such as loans borrowed by local government financing vehicles, were used.

7. What are the current problems?

When Premier Li Keqiang explained his budget plan for the year in March 2019, he said the tax cuts showed the government was willing to “slash its own wrist” to help the economy. But the process to take advantage of some of them was so complicated that companies simply chose not to bother as the administrative costs would have been higher than the savings, a think tank connected to the Ministry of Finance said in October. To properly account for the various taxes, companies must constantly classify all their revenue and spending, and also gain the approval of local tax authorities, the report said. On infrastructure, it’s become difficult to find profitable projects after a decade of fast expansion, and tighter control over local government borrowing also constrained growth, according to economists at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

8. What to do?

Whether large-scale tax cuts are effective depends on how the hole in budgets is filled, and if local authorities have enough alternative resources to pay for social welfare and construction, according to the finance ministry research. Cutting taxes, increasing fiscal expenditure and also containing the deficit is an “impossible fiscal trinity,” and some local authorities may have to strengthen tax collection or resort to off-balance-sheet borrowing to make ends meet, it said.

9. What about debt?

Central and local government debt together amounted to around 40% of gross domestic product by August 2019, up from 37% at the end of 2018, according to Bloomberg Economics. That doesn’t include debt raised through local government financing vehicles and other off-balance-sheet channels, as those are officially counted as corporate debt, even though investors basically expect governments to step in if there is a problem. Overall, the campaign to curb excessive lending remains in place -- the outstanding amount of debt in the non-financial sector as a share of GDP edged up only moderately in 2019 after a decline in 2018. The leverage ratio could rise further in 2020 as the authorities ease their grip on lending to cement economic stabilization and deal with the coronavirus crisis.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on China’s monetary policy toolkit, and its mounting debt default problems.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Shuli Ren asks whether China’s central bank has things under control, and Andy Mukherjee looks at Hong Kong’s experiment with cash handouts.

- Slow but steady: China’s fight to get back to work as it battles the coronavirus.

- For provincial governments, depleted coffers make fighting the pandemic tougher.

- Bloomberg Economics offers insight on China’s likely moves.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg