Understanding the Virus and Its Unanswered Questions

Understanding the Virus and Its Unanswered Questions

(Bloomberg) -- It’s taken scientists time to understand that the novel coronavirus that emerged in late 2019 in central China behaves differently than similar pathogens, producing missteps in the response. The list of known symptoms of Covid-19, the disease it causes, also has grown, complicating efforts to diagnose and treat it. And the virus has yet to give up all its mysteries, creating uncertainty about when the pandemic might end.

1. How is this virus different?

Unlike the coronavirus responsible for the 2002-2003 outbreak in Asia of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, this new one can spread via people who are infected but have yet to develop symptoms, or don’t at all. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 40% to 45% of SARS-CoV-2 infections occur without symptoms. A study by researchers at the Yale School of Public Health’s Center for Infectious Disease Modeling and Analysis found “silent” transmitters are responsible for more than half of the cases in Covid-19 outbreaks. What’s more, the new virus has a relatively long incubation period -- the time between infection and the appearance of symptoms -- enabling it to spread silently in a community before being detected. The interval is about five to six days compared with two days for the flu, which spreads the same way and is the most common cause of pandemics. The stealthy nature of the coronavirus wasn’t well understood at first and contributed to the staggered and uneven quality of the response.

2. Why wasn’t it contained?

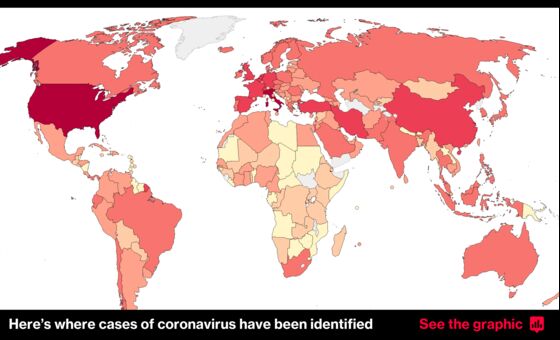

On Jan. 23, China imposed the most extensive quarantine in known history in Hubei province, where the outbreak began in the capital Wuhan, an industrial city of 11 million. By then, however, the virus had been seeded in other places. Starting in early February, many countries introduced travel bans but not before the virus had reached around the world. Governments issued stay-at-home orders and mandated “social distancing” to “flatten the curve” of new infections. But the economic toll propelled reopenings that in many places brought a surge in new cases, sometimes followed by new movement restrictions. It took months for some governments to recommend or mandate that people wear masks in public to counter the virus’s silent spread, and many still haven’t done so.

3. What’s the biggest mystery about the virus?

One major question is whether those who get the coronavirus emerge with immunity. Generally speaking, infections prompt the body to develop antibodies that protect against reinfection, although there are notable exceptions such as HIV and malaria. By mid-year a slew of antibody test kits were available, including some that could be taken at home. Many tests, however, weren’t reliable. What’s more, researchers still don’t know whether the presence of antibodies means someone has immunity, or how long that protection might last. With the main coronaviruses that cause the common cold, immunity generally doesn’t last very long. In Hong Kong, a man tested positive for the coronavirus in late August after recovering from a different strain in April, in what scientists said was the first documented case of reinfection. The man had no symptoms the second time, however, suggesting his immune system provided some protection, according to doctors. Dozens of reinfections have since been reported, according to a tracker maintained by the Dutch news agency BNO News. In other cases, some patients have tested positive weeks after their symptoms went away, but it’s unclear whether they had a new infection or lingering traces or a re-eruption of the first one.

4. What are the other unanswered questions?

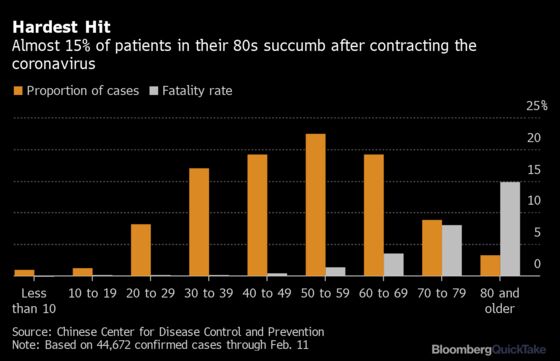

- How deadly is it?: Calculating the fatality risk in the midst of an outbreak is difficult because many cases and deaths go uncounted. Also, countries have different criteria for what deaths they include in their Covid-19 tallies, making the probability of dying a topic of debate throughout the pandemic. The infection-fatality risk (IFR) -- or the risk of death among all infected individuals, including those with asymptomatic and mild infections -- is the most reliable measure. Modeling released in October by Imperial College London estimated that the IFR ranges from 0.14% to 0.42% in low-income countries, to 0.78% to 1.79% in high-income countries, with the differences in those ranges reflecting the older median age in high-income populations. The IFR for the seasonal flu is about 0.039%. The Imperial College research suggested that the risk of death from Covid-19 doubles with about every 8 years of age. It’s also vastly higher for those with underlying conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity. As more time passed, the disease appeared to become less deadly in some countries for a variety of reasons including greater knowledge of how to treat it. Apart from the scourge of HIV, which has stretched over four decades, this is poised to become the deadliest pandemic since the 1918 influenza that infected approximately a third of the world’s population, killing an estimated 50 million people.

- Is it seasonal?: In temperate climates, seasonal flu tends to flare in winter and recede as spring arrives, as do the coronaviruses that cause the common cold. That gave rise to hopes that summer weather in the Northern Hemisphere would keep Covid-19 in check there. Although epidemics were seen in the summer, Covid-19 cases resurged in late 2020, corresponding with cooler fall weather. Evidence for a seasonal effect is supported by experiments showing the virus remains infectious on surfaces for much longer in cooler, drier weather than in the summer.

- What are all the ways it spreads?: Person-to-person close contact is widely considered the dominant mode of infection, because those infected expel droplets carrying virus particles when they speak, sing or just breathe normally. There are other pathways which are considered less common. Scientists have implicated smaller particles called aerosols, which can float farther and for longer, adding to evidence that suggests good ventilation and face masks reduce the risk of infection. Both droplets and aerosols can contaminate surfaces when they land. Such tainted surfaces are called fomites, and people who touch them can transfer virus particles to their own nose, mouth or eye and become infected. Scientists at the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness showed SARS-CoV-2 is “extremely robust,” surviving for 28 days on smooth surfaces such as the glass found on mobile phone screens and plastic banknotes at room temperature, or 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit). That compares with 17 days survival for the flu virus. Researchers continue to investigate the risk that the coronavirus can spread through feces.

- What circumstances are dangerous?: Evidence increasingly suggests that most people contract the virus via exposure to an infected person in an enclosed space for longer than a few moments. Spread of the virus in an outdoor environment appears to be relatively uncommon. Researchers have begun to conclude that so-called super-spreading events play an outsized role in the pandemic. These are episodes in which a single individual infects a cluster of people, for instance at a bar, a funeral or a choir practice.

- Where it came from: When the virus first emerged in early December in Wuhan, attention focused on a market where live animals were butchered and sold. Early cases not tied to the market suggest it wasn’t where the virus originated but probably where it subsequently spread. The viral genome is closely related to several coronaviruses found in bats. Diseases transmissible from animals to humans, sometimes referred to as zoonoses, comprise a large percentage of all newly identified infectious diseases. U.S. and Chinese officials have traded accusations, though without evidence, that the other is responsible for releasing the virus.

5. What have we learned about the virus?

About 80% of cases have mild or no symptoms, 15% are severe and require oxygen, and 5% are critical, requiring ventilation, according to the World Health Organization. As of mid-year, people 65 and older have accounted for about 80% of deaths. The earliest recognized symptoms of Covid-19 were fever, dry cough and tiredness. Over time, the WHO added less common manifestations: aches and pains, nasal congestion, headache, conjunctivitis, sore throat, diarrhea, loss of taste or smell, a skin rash or discoloration of fingers or toes. Complications include failure of the respiratory and other vital systems, septic shock and blood-clotting disorders. Some people who have recovered from Covid-19 have reported lingering impairments such as scarred lungs, fatigue and chronic heart damage, although the long-term picture is still evolving.

6. What should we watch for?

There are a few things:

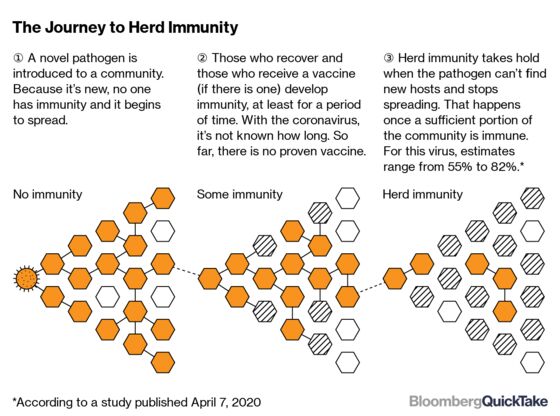

- Herd immunity: When a large portion of a community (“the herd”) becomes immune to a disease, transmission of it from person to person slows and eventually stops. As a result, the whole community becomes protected, not just those who are immune. The term was historically used in the context of immunization. Since the pandemic, some governments and public health authorities have advocated for allowing the SARS-CoV-2 virus to spread naturally among younger people for whom infection is less likely to result in severe disease, while protecting older people and others who are more vulnerable, thereby relying on community infection to create herd immunity. A July survey found almost 60% of people living in some of India’s biggest slums had antibodies, which may help explain a steep drop in new infections there. The herd immunity strategy has attracted fierce debate. It isn’t yet clear if infection with SARS-CoV-2 protects against future infection or for how long. Even if infection creates long-lasting immunity, a large number of people would have to become infected to reach the herd immunity threshold, estimated to range from 55% to 82% for SARS-CoV-2. Assuming it’s 70%, more than 200 million Americans would have to recover from Covid-19 to halt the epidemic in the U.S. If many people become sick with Covid-19 at once, the health system could quickly become overwhelmed. This amount of infection could also lead to serious complications and millions of deaths, especially among older people and those who have chronic conditions. SeroTracker, a repository of data from antibody studies, tracks estimates from around the world. In the U.K. as of June, an estimated 5% of people had coronavirus antibodies. The figure was measured in May at 17% in London and 22.7% in New York City.

- Better treatments: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in October approved the Gilead Sciences Inc. drug remdesivir, making it the first to obtain formal clearance for treating the coronavirus. Research had shown it helped hospitalized patients recover from Covid-19 more quickly than standard care. Subsequent studies from the World Health Organization reported a lack of impact on patient deaths. However, some infectious disease specialists say such antivirals are most likely to be effective when used early, before the infection overwhelms the body. In August, the FDA gave emergency use authorization to what’s known as convalescent plasma -- an immunity-rich component of blood donated by recovered patients -- for use in certain cases, although the benefits of the experimental therapy were still under study. In June, the low-cost anti-inflammatory dexamethasone improved survival in patients with Covid-19 in a study, becoming the first treatment to show life-saving promise. More than 300 projects have been launched to develop and test treatments.

- Vaccines: China and Russia have said they are using special regulatory provisions to deploy vaccines before they have undergone full testing, sparking concerns among public-health specialists about safety and political interference. Other vaccines are in final-stage trials including in the U.S. and U.K. Around the world, some 170 are in development. Bringing a new vaccine to market ordinarily takes a decade on average, but authorities, companies and researchers are collaborating to compress that to just months.

The Reference Shelf

- Subscribe to a daily update on the virus from Bloomberg’s Prognosis team.

- Bloomberg tracks developments on potential coronavirus drugs and vaccines.

- Click VRUS on the terminal for news and data on the coronavirus and here for maps and charts.

- The CDC has a coronavirus web page, as does the WHO.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.