To the EPA, ‘Forever Chemicals’ Are a Big Problem Now

To the EPA, ‘Forever Chemicals’ Are a Big Problem Now

(Bloomberg) -- What do you do about lab-made chemicals that are in 99 percent of people in the U.S. and have been linked to immune system problems and cancer? Whose bonds are so stable that they’re often called "forever chemicals"? Meet PFAS, a class of chemicals that some scientists call the next PCB or DDT. For consumers, they are best known in products like Scotchgard and Teflon. For businesses, PFAS are a puzzle that has already created billions of dollars worth of liabilities. But 70 years of unchecked proliferation may be ending as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will announce what to do about them -- by the end of 2019.

1. What are PFAS?

They are used to make hundreds of everyday products, from stents to firefighting foams, and turn up in the supply chain of the textile, paper and electronics industries. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS (“PEE-fas”), previously called PFCs, FCs or fluorocarbons, come in 5,000 or more varieties. Some have been made since the 1950s by companies like 3M Co. and DuPont (now DowDuPont’s spinoff Chemours Co.). They’re characterized by bonds between carbon and fluorine that are among the strongest in organic chemistry. Consumers may be more familiar with the names of two of the most studied forms, PFOS (Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid), once used in Scotchgard; and PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid), also sometimes called C-8, once used to make Teflon. PFAS are also found in high levels in the water of some U.S. communities.

2. What are they in?

Their consumer-friendly abilities were discovered by accident -- in 1938 when a DuPont scientist was experimenting with refrigerants, and in 1952 when a 3M researcher splashed an experimental mixture on shoes, which then became stainproof -- giving rise to 3M’s Scotchgard. Now, they’re in many types of outdoor clothing, camping gear, shoes, textiles, coated papers for fast-food takeout, firefighting foams and surfactants for electronics manufacturing, for a start. Chemours’ Teflon manufacturing also relies on them. The medical equipment and construction industries depend on them too. Private labs have warned of cross-contamination from PFAS in blue chemical ice packs, sunscreens and Post-It Notes. Some varieties surprised grocer Whole Foods Market and suppliers of its takeout containers. And because the chemicals also get around on their own, they pop up in polar bears, newborn babies, and kale.

3. Are they dangerous?

It depends who you ask. A scientific panel that monitored the blood and health of about 70,000 people in West Virginia and Ohio from 2005 to 2013 who lived near a DuPont Teflon plant found a “probable link” between cases of kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, high cholesterol and pre-eclampsia and PFOA. Animal studies have shown PFOS affects the ability of cells to communicate with each other -- potentially hampering the immune system’s ability to destroy viruses and the rogue cells that cause cancer. In Minnesota, near a 3M plant, there’s been a debate over whether they’re linked to problems like lowered fertility and childhood cancer.

4. Is there a big difference between varieties?

That’s not clear. Manufacturers distinguish between what are known as long-chain and short-chain varieties. Long-chain PFAS have more than eight fluorine-carbon bonds. Around 2000, manufacturers began switching to short-chain PFAS, some of which have been shown to spend less time in the body. The FluoroCouncil, which represents some manufacturers, says PFAS are “diverse” and that as a whole, PFAS “meet relevant standards for the protection of human health and the environment.” It also says current PFAS used are all “short-chain” types, which “do not meet criteria for chemicals of concern based on their environmental fate and potential for adverse health effects.” Chemours, in an emailed statement, said Teflon nonstick coatings meet “regulatory standards and are safe for their intended use.” 3M said that studies haven’t found Scotchgard ingredient PFBS at quantifiable levels in the general U.S. population. “We are committed to responsible environmental stewardship and take significant steps to ensure our products are safe,” the company said in a statement.

5. Do people agree with that?

Many scientists do not. Some signed a “Helsingor Statement” in 2014 and a “Madrid Statement” in 2015, saying industries should consider avoiding all PFAS. They caution that even if short-chain PFAS accumulate less in living tissue, they persist in the environment, where their carbon and fluorine bonds can recombine to create other varieties of PFAS. Companies also may use more of them to get the same effects that long-chain versions provided. While the American Chemistry Council questioned a recent draft EPA analysis that raised concerns about immunotoxicity, environmental and health advocates said the agency didn’t consider the mix of PFAS any one person is exposed to. They said the data suggest that some short-chain PFAS -- -- including those currently used in Scotchgard spray and Teflon manufacturing -- may be as harmful to the liver, thyroid and kidney as the long-chain versions they replaced. Chemours, in its own January response to the EPA analysis, took issue with some of the liver findings.

6. Who’s been affected?

Around 110 million Americans have drinking water with traces of PFAS, according to the Environmental Working Group’s map data. And that’s just water -- indoor dust and food are also said to expose people. There are also reports of pollution in Belgium, Germany, Japan, Australia and the Netherlands, and contamination through agricultural use of biosolids from wastewater treatment plants, and landfills where chemical-laden products were disposed of.

7. What kind of action has there been on PFAS?

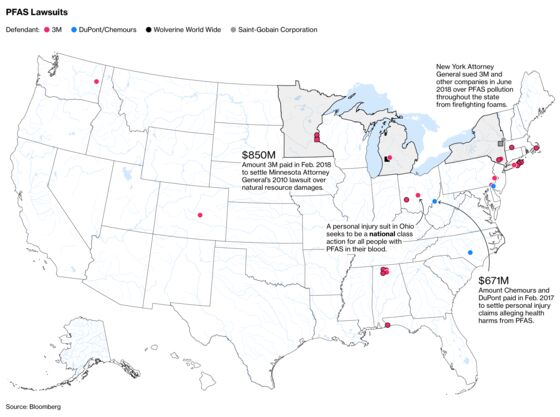

The EPA has been considering nationwide rules, and environmental activists have urged it to set enforceable limits for tap water. They also want the chemicals added to a national law that can force clean-up at Superfund sites. But in its Feb. 14 announcement, the EPA delayed a decision until the end of 2019. Health advocates called it yet another example of 20 years of foot-dragging, and said the wait will make contamination worse. The lack of national limits has kept the burden on municipalities and states, many of which have lowered their own guidelines for acceptable levels in water. Lawsuits have also spurred action: A settlement forced DuPont and its Chemours spinoff to pay $671 million to people in West Virginia and Ohio after the science panel found the “probable links” to the six diseases. And in 2018, Minnesota got an $850 million settlement from 3M to spend on filtration and cleanup. Many suits have merged into a “mega” case. One on behalf of a firefighter seeks to become a class action for anyone in the U.S. with the chemical in their blood.

8. What’s this mean for businesses who made or used PFAS?

Many makers of the chemicals face lawsuits, while DowDuPont has been partly distanced from liability because of the Chemours spinoff. Companies that use PFAS or may unwittingly have it in their supply chains face potential for new regulations, backlash from consumers and costs to reformulate. Some, like Patagonia Inc. and Columbia Sportswear Co., seek to phase the chemicals out, with Columbia even boasting PFAS-free products. Others, like Procter & Gamble Co., have responded to legal claims by saying they didn’t use the chemicals. And still others have made changes in response to pressure from advocates, including Whole Foods and its supplier Cascades Sonoco Inc., which recently moved away from the chemicals.

9. Can I do anything to limit my risk?

Those who suspect high levels should try and get tested by a physician. Some studies suggest blood-drawing, or phlebotomy, might reduce PFAS in blood, but research is preliminary. Childbearing can decrease levels, though unfortunately that’s by passing them on to the child. When it comes to avoiding exposure, you can:

- Check to see if PFAS are in your area on the EWG map, check if your municipality filters for them or get an in-home filter.

- Some groups say to ditch non-stick cookware -- from pie pans to rice cookers -- especially if they’re scratched. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency has a guide.

- Dr. Philip Landrigan, a children’s health advocate, has recommended not using Scotchgard “even as we wait for more definitive information” about the current formulation.

- Articles abound that identify PFAS or PFAS-free cosmetics, stain-proof fabrics and outdoor gear.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg News deep dive story into 3M’s history with PFAS.

- The Devil We Know, a 2018 documentary from filmmakers Stephanie Soechtig and Jeremy Seifert.

- Stain-Resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof, and Lethal: The Hidden Dangers of C8, a book.

- Bloomberg News story about Chemours and pollution in Cape Fear.

--With assistance from Christopher Cannon.

To contact the reporter on this story: Tiffany Kary in New York at tkary@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anne Riley Moffat at ariley17@bloomberg.net, ;John O'Neil at joneil18@bloomberg.net, Lisa Wolfson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.