This Is Bad, But It’s Not Looking Like the Depression

This Is Bad, But It’s Not Looking Like the Depression: QuickTake

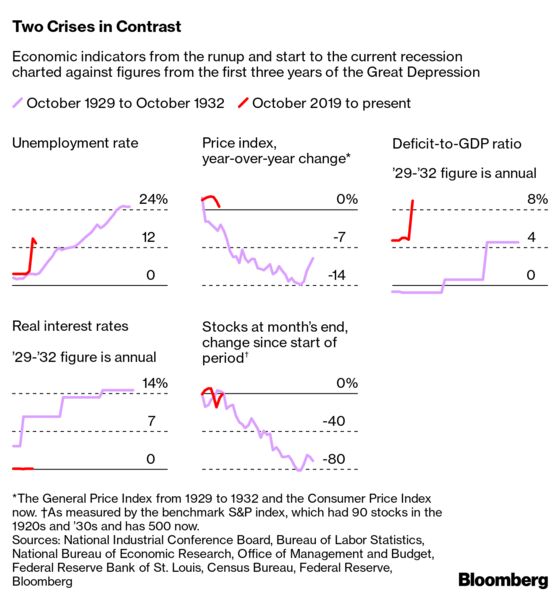

(Bloomberg) -- Since unemployment skyrocketed in March and April, there has been no end of discussion about possible similarities between the Covid-19 recession and the Great Depression. The median forecast for the May unemployment rate from economists surveyed by Bloomberg was 19.5%, worst since the 1930s. Instead, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said the unemployment rate fell to 13.3% from 14.7% in April as the economy created 2.5 million jobs. But even before the jobs report came out, other measures of the health of the economy were indicating that the U.S. economy was considerably stronger than during the Depression. Here’s a tour of the data.

Unemployment rate

Today’s jobless numbers aren’t directly comparable with those from the 1930s because before 1948 the government didn’t collect employment data the way it does now. Still, people have tried. On its website, the Bureau of Labor Statistics cites 1970s research by John Dunlop of Harvard University and Walter Galenson of Cornell University calculating that the annual jobless rate peaked at 24.9% in 1933. The National Industrial Conference Board, a business organization now known as the Conference Board, estimated at the time that the monthly unemployment rate topped 20% for most of 1932 and 1933, peaking at 25.6% in May 1933. Kathryn Edwards, an associate economist at RAND Corp., a research organization, says it would be a mistake to put too much faith in those Depression-era estimates. What’s safe to say, she says, is that “this is the worst we’ve ever had” since then.

Length of unemployment

The longer joblessness lasts, the more damage it does. Many economists expect the unemployment rate to fall quickly as the economy reopens. According to BLS data, 73% of the unemployed in May were considered to be on temporary layoff, down from 78% in April but up from a pre-recession average of 13%. On the other hand, that 73% figure is inflated by a change in the BLS’s methodology. Usually layoffs are considered temporarily only if a person has been given a return date or expects to be recalled within six months. The BLS said in a note accompanying the April jobs report that “in light of the uncertainty of circumstances related to the pandemic” it decided to call all coronavirus-related layoffs temporary even if the person didn’t know when he or she was returning.

Wages and prices

Wages fell broadly during the Depression, dropping an estimated 34% in manufacturing and 17% in railroads from late 1929 to 1932, according to a 1933 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Prices for farm products -- a sector that then involved about a quarter of all workers -- fell in the early years of the Depression because demand was so weak: An index of farm prices fell to 44 in 1932 from a base of 100 in 1926. Even though consumer prices also fell, the drop in earnings meant that even many people who still had jobs couldn’t keep up with interest payments on mortgages and other types of debt. Things aren’t likely to be as bad this time, although prices did fall in March and April and some companies have cut pay temporarily. The Federal Reserve said in April that most of the system’s 12 regional banks reported “general wage softening and salary cuts except for high-demand sectors such as grocery stores that were awarding temporary ‘hardship’ or ‘appreciation’ pay increases.”

Bankruptcies

This is one category in which the current recession is likely to appear worse than the Depression. Bankruptcy filings remained rare in the 1930s in large part because the law was tilted against debtors and bankruptcy carried more of a stigma than it does now. Until the Chandler Act of 1938 companies filing usually had to liquidate their assets, instead of getting to work out a restructuring plan. In contrast, there’s no doubt that the pandemic recession will cause a surge in bankruptcies, although they are only starting to show in the data. Hertz Global, J.C. Penney Co. and Neiman Marcus were among the 28 companies that sought bankruptcy protection in May, bringing the total this year to 99 and putting 2020 on pace to top the 2008 level.

Malnutrition

A 1932 study by the New York City Health Dept. found that 20.5% of the children examined were suffering from malnutrition. The problem was likely worse elsewhere because New York at least offered food aid of $2.39 a week per family, according to one textbook. That’s the equivalent of $60 today. Access to food is also a problem in this recession. In a Household Pulse Survey conducted May 14-19, the Census Bureau found 14% of households with children under 18 didn’t have enough to eat sometimes or often in the previous week.

Government aid

In the early years of the Depression there was no safety net aside from help provided by churches, charities, labor unions and family members. The first state unemployment insurance system was legislated by Wisconsin in 1932. Social Security and the Works Progress Administration, two of the most famous New Deal programs, weren’t signed into law until 1935. A measure of how little the federal government did is that it ran a budget surplus in 1930 and a deficit of only half a percent of gross domestic product in 1931. Despite that stringency, Franklin Roosevelt ran for president in 1932 on a promise to balance the budget. The biggest the deficit ever got during the 1930s was 5.8% in 1934. This time, Congress has acted both more quickly and more aggressively. As a result of large stimulus programs, in April the federal budget deficit nearly doubled to 9% of GDP. Government social benefits accounted for a third of personal income in April, up from 19% before the pandemic hit, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Those who lost their jobs and were able to file for unemployment are doing pretty well,” says Susan Houseman, research director at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, Michigan. “Over half are making more than when they were fully employed.”

Interest rates

The Federal Reserve helped cause the stock market crash of October 1929, which triggered the Depression, by raising interest rates to stop speculation in stocks. In 1932 it raised rates again to defend the value of the dollar. At the same time, prices were falling, so real rates — that is, rates adjusted for inflation or deflation — reached crippling highs. In 1932, rates on four- to six-month commercial paper borrowings were 2.73% but consumer prices fell 12%, producing a real interest rate of 14.73%. When money costs that much it strongly discourages borrowing. This April, in contrast, the average interest rate on three-month commercial paper was 0.98% and the yearly change in consumer prices was 0.3%, for a more affordable real interest rate of 0.68%.

Stock market

Talk of another Depression was rampant in March, when the stock market seemed to be in freefall. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index fell 34% in just over a month, even faster than stocks’ decline in the 1930s. But the index has since recovered most of the lost ground, which helps economic growth by making consumers and businesses feel wealthier and more optimistic -- though there’s no shortage of worries that the market may be too sanguine about the course of the pandemic. In the Depression the predecessor to the S&P 500 fell 86% from peak to trough.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.