How Vast Covid Response Remade Central Bank Toolkits

The Stimulus Toolbox to Help Virus-Stricken Economies

(Bloomberg) -- It was unprecedented in the history of central banking: intervention without limits. The pledges this spring by the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and some of their counterparts to make a seemingly infinite ocean of money available to fight the disruption caused by the coronavirus marked a dramatic expansion of their traditional role. Central banks became backstops to entire economies. Their swift action calmed financial markets, leading to rebounds in many asset prices. But even central bank leaders acknowledge that restoring economic growth is more than they can do alone.

1. What’s different?

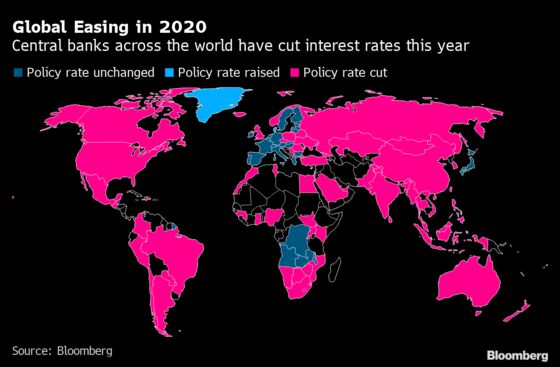

The traditional tool of central banking is its control over interest rates. The Fed’s first response to the crisis was to bring its main interest rate back to near zero in March; the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan were already below zero. Central banks also ramped up bond-buying programs, known as quantitative easing, to pull down long-term rates. But it wasn’t enough.

2. Why not?

The world had never faced a downturn of this speed, scale or severity. And while low interest rates usually work by making spending more attractive, cheaper borrowing costs don’t do much for factories starved of materials by supply chain disruptions, or help locked-down or nervous consumers return to shopping, traveling or eating out.

3. What did central banks do?

To keep the flow of credit from freezing up, central banks offered themselves as massive short-term lenders, willing buyers of good (and not-so-good) assets and suppliers of their currencies for other central banks. They also massively expanded the speed and scope of their bond buying, adding a combined $2.7 trillion to their balance sheets in three months. Proclamations from policy makers including phrases such as “no limits” and “as much as necessary” not only calmed markets but made it easier for governments to launch expansive, deficit-funded relief programs by cutting their borrowing costs.

4. How else did the banks try to buy time?

Broader lending programs were meant to carry companies and individuals over the economic abyss created by pandemic lockdowns. By May, when more than 20 million Americans had filed for unemployment benefits, the Fed had supplied $2.3 trillion in credit. Its programs supported big companies through the corporate bond market and small- and medium-size businesses by buying bank loans; both approaches gave it far greater involvement in the fate of individual firms than it had had in decades. The ECB’s lending programs offered up to 3 trillion euros ($3.4 trillion).

5. That’s a lot! Was it enough?

Fed Chair Jerome Powell expressed concern in June that what he called America’s “jobs machine” — its small- and medium-size firms — could tip into bankruptcy. He cautioned against pulling back on government stimulus too soon.

6. What are the risks?

The immediate danger central banks were trying to fend off was deflation — the kind of price decreases that made the Great Depression of the 1930s so hard to escape. But some prominent economists predicted that such a massive infusion of money will inevitably lead to inflation later. Others worry about the erosion of central bank independence that may come from policies that come close to directly bankrolling governments, or buying the debt of individual companies. The effort exposes central bankers to risks in a way they had long shunned, as well as to charges of picking winners and losers. A rebound in U.S. stocks in June that overlapped with mass protests over racial injustice highlighted concerns over inequality, leading some lawmakers and commentators to question whether the Fed had gone too far to prop up markets and companies.

7. Where do central banks go from here?

By mid-year, central banks appeared to be stuck in support mode until the pandemic passes, and they may even have to add more stimulus to aid the recovery. Once we get there, winding down those policies may be challenging. In the 12 years between the 2008 financial crisis and the arrival of the pandemic, economies around the world remained fragile enough that the Fed was almost alone in feeling able to begin the process of “normalizing” monetary policy by raising interest rates. That process could take even longer now that the Fed has announced a switch to “inflation averaging,” meaning it might let price hikes exceed its 2% target for some time if they’ve run below that figure for a while.

The Reference Shelf

- How the coronavirus is delivering a twin supply-demand shock.

- QuickTakes on the a roiling debate on inflation, on the diminishing effectiveness of central bank policy and on helicopter money. Another on what you need to know about the coronavirus.

- Hong Kongers get cash handouts.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Mohamed A. El-Erian assesses the obstacles ahead for the Fed.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.