As Covid Vaccine Nears, There Are Reasons for Hope and Caution

The Keys to Speed in Race for Vaccine, and Its Perils: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) --

Thousands of researchers in more than 30 countries have been collaborating and competing this year on more than 200 projects to develop a vaccine against the novel coronavirus in record time. In the most encouraging scientific advances so far, two vaccines have delivered positive news that their shots were more than 90% effective in late-stage trials. However, a number of hurdles still need to be cleared, and testing that was halted on other promising candidates highlighted the uncertainties and risks that developers face. With the best hopes for ending the pandemic resting on the global deployment of an effective vaccine, the stakes are immense.

1. Where do things stand?

The vaccine developed by Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE was more than 90% effective in preventing Covid-19, based on an early analysis of data from a trial of tens of thousands of volunteers, while Moderna Inc. said its vaccine was 94.5% effective in a preliminary analysis. The results pave the way for the companies to seek emergency-use authorizations from regulators if further research shows the shots are also safe. Already, China and Russia have said they are using special regulatory provisions to deploy domestically developed vaccines before they have undergone full testing. The use of such shots outside of clinical trials raised concerns among researchers and regulators elsewhere. In an unusual public letter, nine U.S. and European companies in the forefront of the Covid vaccine effort pledged to avoid shortcuts on science.

2. What are the worries?

Widespread use of vaccines that aren’t fully tested would put the people who get them at an elevated risk of side effects that might have been discovered in clinical trials. The hazards were underscored in September when a volunteer in a U.K. trial of AstraZeneca Plc’s experimental vaccine, developed with researchers from the University of Oxford, developed an unexplained illness. The U.K. trial paused and then resumed after the company said a review recommended it was safe to do so, then AstraZeneca in October was cleared to restart a U.S. study that had been halted for more than a month. In October, Johnson & Johnson also temporarily paused its Covid-19 vaccine study after a participant experienced an unexplained illness.

3. What safety issues have arisen with vaccines before?

In the 1960s, an experimental vaccine against RSV, a common respiratory virus, not only failed to protect children, but made them more susceptible. Two toddlers died. Safety issues have also arisen in new vaccines after their approval; thorough testing beforehand minimizes chances of that. Documented reports of unexpected side effects from novel vaccines are different from the persistent and incorrect belief that well-established vaccines against childhood diseases carry significant risks. That myth has contributed to significant minorities of people in some countries saying they’d refuse to receive a Covid vaccine. A fumbled shot against the disease could further damage perceptions of vaccines.

4. What’s the process for minimizing safety risks?

An inoculation must clear a higher bar than a treatment because it’s injected into healthy individuals. After testing a vaccine in animals, developers must show it’s safe and effective in humans. That usually happens in three phases, starting with tests in a small number of people aimed at achieving the strongest immune response without significant side effects. Larger-scale studies follow. The final leg, which often requires thousands of patients and lasts years, evaluates how safely and effectively a vaccine prevents infection or disease in the population it’s intended for. If a vaccine passes these tests, it must then satisfy regulators and be produced in large quantities. The process of bringing a conventional vaccine from inception to the finish line takes on average nearly 11 years. The record is four years, for development of the Merck & Co. mumps vaccine in 1967. And just 6% of experimental vaccines make it all the way.

5. How has the development of Covid-19 vaccines been sped up?

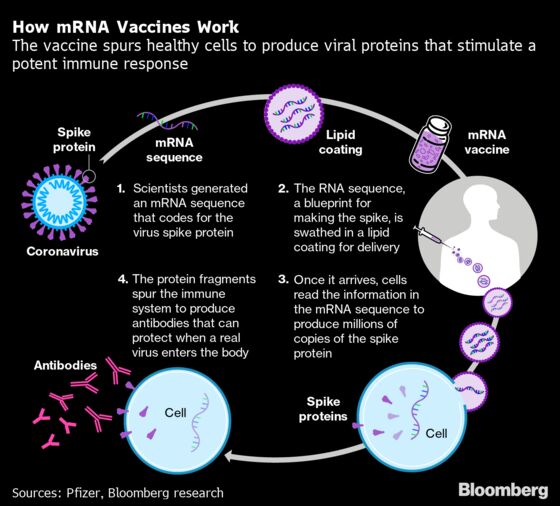

- Using innovative vaccine designs. About a fifth of the Covid-19 vaccine projects, including the Pfizer-BioNTech venture, rely on so-called gene-based technology. It uses the body’s own cells to produce proteins that trick the immune system to react as if it’s been invaded by a pathogen, training it for the real thing. These experimental vaccines can be made more quickly than conventional ones, which contain an inactivated or weakened version of a pathogen, or a piece of it. Using a gene-based platform, Moderna Inc. and the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases began the first human test of an experimental Covid-19 vaccine a record-short 66 days after Chinese researchers made public the coronavirus’s genetic sequence. An important caveat: No gene-based vaccine has yet been licensed for humans, although a few are in use in veterinary medicine.

- Compressing steps. Another reason Moderna was able to move so quickly was that rather than testing its vaccine in animals before moving on to humans, it did both simultaneously. For Covid-19 vaccines, U.S. and European regulators in March waived the requirement for proving efficacy in animals first.

- Building on past work. The Oxford researchers got a jump by betting on a method they’ve used in their ongoing work on a vaccine against Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which is caused by a related coronavirus. That vaccine appeared to be safe in animal and early human testing. The technique uses a modified cold virus as a harmless carrier to expose the immune system to the spiked protein that projects from the surface of a coronavirus rather like a crown, hence the name.

- Fast-tracking regulatory consent. China and Russia have already done this. Guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration leaves open the possibility of a so-called Emergency Use Authorization, or EUA, for a Covid-19 vaccine. The FDA says it would demand two months of safety data before it would review any application for an EUA and any candidate submitted would need to be considered by an independent panel.

6. Would anything else quicken things?

Some researchers propose adopting so-called challenge trials. In the final stage of testing, researchers typically give a vaccine to one group of volunteers and a placebo to another, then wait to see whether significantly fewer in the first group develop the targeted infection. That takes time. A quicker but riskier alternative is to inject volunteers with the vaccine, then deliberately expose them to the pathogen. Such challenge trials are the basis for animal studies of vaccines, and they’ve been used in human tests of cholera, malaria and typhoid shots as well. Some prominent scientists have argued that the urgency of a Covid-19 vaccine justifies their use now, and the website 1daysooner.org has collected the names of tens of thousands of people who say they’d participate. Skeptics say it’s unethical to use this trial design until there are better, proven therapies to treat those who would become sick.

7. Is a vaccine just a matter of time?

Despite the unprecedented mobilization, there’s no guarantee developers will deliver an effective shot. A vaccine against HIV has eluded scientists for decades, as has a single shot that would prevent all strains of flu, though researchers think the coronavirus is an easier target because it doesn’t appear to mutate as rapidly as those viruses do. How effective a Covid-19 vaccine might be and how long its protection would last are other crucial questions.

8. If a vaccine pans out, how does it get mass produced?

Given the high failure rate for experimental vaccines, developers usually don’t invest in the capacity to manufacture lots of doses before a new one looks like a winner. In this case, some of the most prominent players in the race have scaled up production facilities already. Still, deploying a new vaccine to the world is a gigantic undertaking with challenges including sourcing the specialized glass that doses are stored in, making sufficient needles for injections, and ensuring vaccines are appropriately refrigerated throughout the supply chain.

9. How would a vaccine get delivered to every corner of the globe?

Some populations are bound to get vaccine supplies before others. One risk is that wealthier nations will monopolize Covid-19 vaccines, a scenario that played out in the 2009 swine flu pandemic. To prevent that, a collaboration called COVAX -- led by the Oslo-based Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, the World Health Organization and Gavi, a global non-profit group focused on vaccine delivery -- aims to raise $18 billion from high- and middle-income countries. Its goal is to ensure that all poor and contributing countries have access to a proven vaccine for those who are at greatest risk, for example health-care workers and the elderly. Health advocates say that distributing vaccines evenly all over the globe isn’t just the ethical thing to do. It’s also critical to ending the crisis.

The Reference Shelf

- Related QuickTakes on coronavirus reinfections, virus mysteries, how it spreads, the challenges of distributing Covid vaccines, vaccine nationalism, myths and facts about vaccines, and the search for better Covid-19 therapies.

- Bloomberg Businessweek examined vaccine nationalism as well as the challenges to develop an inoculation that works.

- A podcast on the rise of vaccine nationalism.

- The World Health Organization keeps track of Covid-19 vaccine candidates and trials.

- A Bloomberg tracker on the coronavirus vaccines and drugs under development.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.