The Great Decoupling? What’s Next for U.S.-China Rift

The Great Decoupling? What’s Next for U.S.-China Rift

(Bloomberg) -- In terms of economic relations, the U.S. and China have been coupling up for decades. So much so that they became the biggest trading partners on the planet starting in 2014. Now, amid trade and technology wars, a pandemic and strained diplomatic relations, the world’s two largest economies appear bound for a seismic “decoupling.” Yet these two giant markets could find that breaking up is hard to do.

1. Are China and the U.S. really decoupling?

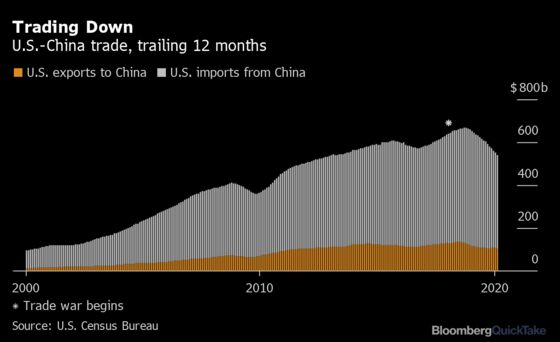

Bilateral trade sank 15% in 2019 after U.S. President Donald Trump began imposing tariffs on Chinese imports and China responded in kind. It had surged by an annual average of 11% from 2001 to 2018, a stretch that included China’s admission to the World Trade Organization and transformation into a global manufacturing powerhouse shipping cheap electronics, toys and clothes to American consumers. The pandemic and new fights over market access are further depressing trade as tensions on multiple fronts provoke what some see as an unavoidable tumble into a new cold war that could rival the old U.S.-Soviet divide. There’s a big difference during this showdown, though: The two combatants’ economies are linked in ways difficult to undo without cost and disruption.

2. What are the other flashpoints?

A growing list of disputes includes alleged spying and intellectual property theft by China. The U.S. sees China’s ambitions in advanced technologies and involvement in foreign communications networks as a threat to national security and has banned American sales of components to various Chinese companies including Huawei Technologies Co., the world leader in 5G wireless technology. The Trump administration began to dismantle Hong Kong’s special trade privileges over China’s move to enact new security laws in the semi-autonomous city in June, which was condemned by the U.S. and its allies. Chinese companies are pulling their shares from trading on U.S. exchanges amid new rules that make it tougher for them to list there.

3. What about the coronavirus?

The crisis provoked a war of words, with officials in both countries accusing the other side, without evidence, of releasing the virus. Beyond that, the shutdown of China’s Hubei province following the initial outbreak in the city of Wuhan — a technology and auto hub — left international companies with supply chains that flowed through the city short of vital parts. That prompted bipartisan calls from politicians to “reshore” production from China to the U.S., echoing a refrain from Trump during the trade war. Those demands intensified as countries realized that they relied heavily on China for protective equipment such as face masks.

4. Is this a watershed?

The pandemic will probably push countries including the U.S. to pressure companies to localize production of crucial health products such as protective gear. But moves to reconfigure supply chains have been under way since at least 2011, when the tsunami in Japan and floods in Thailand put a new focus on managing risks to production and diversifying suppliers. The so-called China+1 sourcing strategy, adopted by many companies that had relied solely on the mainland for their supply chain, accelerated during the trade war. U.S.-owned factories did leave China, but they moved to other low-cost countries rather than to America’s industrial heartland. For example, the U.S. has increasingly turned to Mexico for electrical machinery and to Vietnam for toys, furniture and footwear.

5. Are U.S. businesses getting out of China?

Not so many. Some 84% of U.S. companies surveyed in March by the American Chamber of Commerce in China said they had no plans to move production or supply chain operations out of China because of Covid-19. The Asian country has advantages that are likely to sustain its position as the world’s main factory — mature supply chains, a massive domestic market, well-built infrastructure and skilled labor. Much of the production in China by American companies is aimed at the local market. Even with the trade war raging in 2019, U.S. companies plowed some $14 billion into new factories (including Tesla Inc.’s $5 billion factory near Shanghai) and other long-term investments in the country, about 10% more than in 2018.

6. Does that leave U.S. firms exposed?

The more the U.S. blocks the export of components such as semiconductors and jet engines to China, and imposes tough sanctions on anyone who violates such bans, the more it will force not just Chinese companies to stop buying American components, but also firms from third countries that want to offer their products in China. Businesses fret that selling to China in the future could mean getting America out of the supply chain altogether. Others speculate that the Trump administration’s actions will serve to turbocharge China’s drive to become the dominant force in areas including artificial intelligence and biomedicine.

7. How did it get to this?

Trump brought his “America First” agenda to the White House just as President Xi Jinping was flexing China’s military, economic and technological muscle. Having lambasted China for harming the U.S. economy and stealing American jobs during his 2016 campaign, Trump instigated the trade war two years later with the first imposition of tariffs that eventually applied to around $500 billion of goods. The U.S. had for years -- along with other trading partners --- accused China of playing loose with the rules of international business. For instance, it complained that China forced foreign companies to hand over industrial and technological know-how, or simply stole it.

8. What about the U.S. election?

The desire to check China has been one of the rare unifying forces among America’s polarized politicians. While former Vice President Joe Biden, Trump’s opponent in November, was promoting his “friendship” with Xi as recently as 2016, this was his take on the Chinese president in February: “This is a guy who is a thug.” Trump, meantime, is pledging to scale back the economic relationship with China, “whether it’s decoupling or putting massive tariffs on China which I’ve been doing already.”

The Reference Shelf

- Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. Trade Representative, on finding a path between globalism and protectionism in Foreign Affairs website (subscription).

- An infographic by the U.S.-China Investment Project shows trade and foreign direct investment between the countries.

- QuickTakes on U.S.-China flashpoints; the trade war; Hong Kong’s security laws and special status; and the moves that threaten Chinese listings on U.S. stock exchanges.

- Can a broke U.S. fight a Cold War With China? asks Bloomberg Opinion columnist Hal Brands.

- Trump says “complete decoupling” from China remains an option

- Trade war dents China’s role in U.S. trade.

- Watch Elon Musk to see limits of U.S.-China decoupling.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.