Gold’s Ups and Downs

Gold’s Ups and Downs

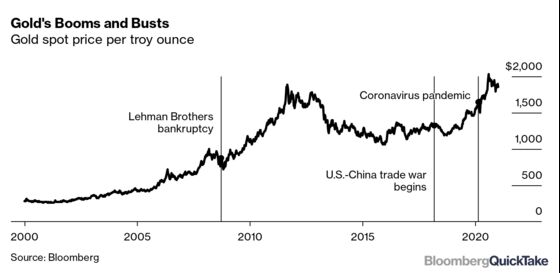

(Bloomberg) -- King Midas lusted after it. The Incas worshipped it. Shiny flakes of it set off a 19th-century rush to California and families in India use it to store wealth on the arms of their daughters. Gold’s allure remains as untarnished as the noble metal itself, even as its price is subject to manias and periods of ambivalence. Bullion is best known as a time-honored haven from inflation, but there are a plenty of conflicting factors at work that can excite investors. As financial markets convulsed during the coronavirus pandemic, gold surged past $2,000 per troy ounce to a record high. That breathed new life into the old question of why investors still bother with what’s likely the most primitive form of money in their portfolios.

The Situation

Gold climbed to a new peak in August 2020 as the health crisis unleashed a torrent of forces that fueled demand for its perceived safety from the turmoil. Moves to cushion the global economy from the worst recession in a generation led to the creation of vast amounts of new money by central banks, sparking the same fears about an eventual resurgence of inflation — and even a possible debasement of the U.S. dollar — that drove gold to its previous record in 2011. Unexpected events and geopolitical tensions can cause bullion to spike, such as salvos in the U.S. trade war with China. That conflict, along with the coronavirus, helped push the metal up 70% from late 2018 to late 2020, even as inflation remained subdued. Some traders pointed to a drop in expected real rates, the closely watched measure of interest rates adjusted for inflation. When interest rates fall, gold becomes more attractive because the opportunity cost of holding the metal — which produces no fixed payments or dividends — decreases.

The Background

Since the turn of the millennium, gold has seen a sevenfold rally, a 45% crash and sustained periods when its price moved very little. The drivers of sentiment change over time. Gold anchored a monetary system until its peg to the U.S. dollar ended in the 1970s. In 1980 the price of gold doubled in six weeks to $850 during a bout of inflation. It slumped in the two decades that followed as central banks shrank their reserves and miners locked in prices for future production. The launch of the first gold exchange-traded fund in 2003, which made it possible for retail investors to trade the metal via their stockbrokers, set off a wave of buying that lifted prices for almost a decade. Then the 2008 financial crisis sent prices up as money was parked in havens amid fear that bond-buying by central banks would lead to hyperinflation — it didn’t. Even so, some money managers never warmed to gold. Warren Buffett, one of America’s best-known investors, expressed his disdain for the metal because it has no inherent yield and isn’t productive like companies or farmland. He wrote in 2012 that investors in gold are simply motivated by their “belief that the ranks of the fearful will grow.”

The Argument

More than perhaps any other investment, bullion acts as an echo chamber for anxieties about the global financial system and an all-purpose protector against unexpected shocks. Critics say that it’s a relic of history and that there are better ways of hedging against uncertainty, by using financial instruments including derivatives. Gold devotees say it offers a simpler way to protect against a wider range of risks. And fundamentally, demand for gold is supported by rising incomes in China, India and other Asian countries, where families load up when funding dowries and there are fewer safe stores of wealth. Some fans of the metal, known as “gold bugs,” believe it should be restored to its place as the guarantor of government-issued currencies to force discipline onto politicians, preventing them from printing money to fund spending or pay debts. (A related argument is made by enthusiasts of some limited-issue cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin.) But there’s a little more to it: Gold can also be considered a so-called Veblen good, which means that as the price rises, its exclusive nature can make it even more desired. When gold rallies it attracts much attention and plenty is written about it — which can tempt even more investors to pile in.

The Reference Shelf

- A Q&A on why gold investors were watching expected real interest rates in 2020.

- Peter Bernstein explores the history of the metal in his book, “The Power of Gold.”

- Comments from former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke on not understanding gold.

- Richard Nixon ends the convertibility of the dollar into gold on August 15, 1971.

- The World Gold Council website has explanations of everything from the gold standard to central bank gold agreements.

- Supply and demand figures.

- Industry facts and specifications from the London Bullion Market Association.

- “The New Case for Gold,” a 2016 book by James Rickards, argues that gold is still an important tool for wealth preservation.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.