The Debt Ceiling

The Debt Ceiling

(Bloomberg) -- The very phrase “debt ceiling” sounds austere and restrictive, as if intended to keep a lid on government spending. In fact, the U.S. federal debt limit was first conceived almost a century ago to make it easier for the government to borrow money. But it morphed into an explosive political tool with the potential to roil financial markets, since a failure to raise the debt ceiling could eventually result in a first-ever default on some of the government’s obligations. President Donald Trump has said that there are “a lot of good reasons” to get rid of the limit altogether. But it’s still here and causing problems anew.

The Situation

After being temporarily suspended by agreement of Trump and the U.S. Congress, the debt limit came back into effect on March 2, restraining the government’s authority to borrow more money. That didn’t mean a crisis was immediately at hand. The Treasury Department is employing what are known as extraordinary measures — withholding regularly scheduled contributions to a federal employee retirement fund, for instance, and using that money to keep paying debts. Those measures could keep the gears turning into September or October and enable the Treasury to continue issuing debt, but the U.S. could default on its debts if Congress has failed to act by then. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, representing the Republican White House, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the highest-ranking Democrat in Congress, are leading negotiations aimed at raising the borrowing limit before Congress leaves Washington for its August recess.

The Background

The federal debt limit was created in 1917 to make it easier to finance World War I by grouping bonds into different categories, thus easing the legislative burden on Congress. Before that, lawmakers approved each bond separately. With World War II looming in 1939, Congress created the first aggregate debt limit, and it was routinely raised without incident until 1953. That year, approval was held up in the Senate in an attempt to restrain President Dwight Eisenhower, who wanted to build the national highway system. Just getting close to the debt-ceiling deadline in 2011 rattled the financial markets and consumers, who feared that home-mortgage and credit-card interest rates would soar and that government payments, such as Social Security checks, might be delayed. S&P even downgraded its rating on sovereign U.S. debt. Since then, there have been repeated political clashes over increasing the limit, including a notable episode in 2013 that saw the cap suspended for the first time.

The Argument

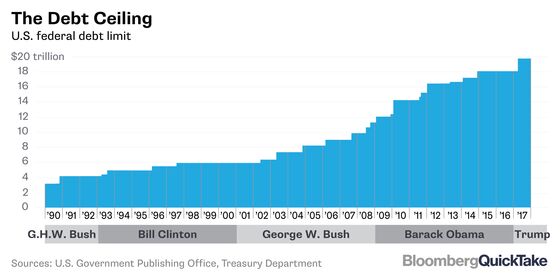

At least one thing is clear about the debt ceiling: It hasn’t restrained the federal debt. That’s in the hands of Congress when it sets levels of taxation and spending, then borrows money when it runs a deficit. Raising the debt ceiling simply lets the government pay for things it has already decided to buy. As a result, some budget experts and commentators want to abolish it, arguing that the congressional battles cost taxpayers money by increasing economic uncertainty, among other problems. Debt-limit supporters say opponents overstate the potential harm and that using it to bargain for spending cuts serves the public interest at a time of historically high debt levels.

The Reference Shelf

- A U.S. Debt Clock displays an up-to-the-second ticker on the national debt and many other fast-moving statistics.

- The Congressional Research Service follows debt ceiling votes and limits.

- The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget aggregates news, documents and other resources on the debt ceiling.

- The Bipartisan Policy Center’s analysis of the debt limit and “extraordinary measures.”

- A Bloomberg QuickTake on the budget deficit.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Laurence Arnold at larnold4@bloomberg.net, Benjamin Purvis

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.