The Deadly Pig Virus That’s Proving Difficult to Beat

The Deadly Pig Virus That’s Proving Difficult to Beat: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- A deadly swine disease that’s plagued pig farmers for years is re-emerging across Asia, illustrating how difficult African swine fever is to combat despite the culling of millions of animals. Hardest hit has been China -- home to half the world’s hogs -- where pork prices soared after a massive outbreak in 2018 and could remain elevated while work on a commercial vaccine continues.

1. What is African swine fever?

A highly contagious viral disease which, in its most virulent form, can be 100% lethal. The virus infects pigs, warthogs, European wild boar, American wild pigs, bush pigs, giant forest hogs and peccaries. There is no licensed vaccine or treatment. It is characterized by high fever, loss of appetite and hemorrhaging on the skin and internal organs. Diarrhea, vomiting, coughing and breathing difficulties are other symptoms. Death comes in two to 10 days on average.

2. Does it threaten human health?

No. Still, the disease can have a significant impact on food security through decreased and lost production, as well as on food safety through the movement of disease-infected carcasses that may not be adequately chilled or frozen, leading to bacterial contamination.

3. How does the virus spread?

Via direct contact with infected animals or ingestion of garbage containing unprocessed infected pig meat or byproducts. The virus is found in all of an infected pig’s body fluids and tissues and can survive in feces for several days, and possibly longer in urine. Animals that recover from the illness can carry the virus for several months. Unprocessed meat must be heated to at least 70 degrees Celsius (158 Fahrenheit) for 30 minutes to render the virus inactive. Analysis of China’s first 21 outbreaks found that feeding pigs swill, or food scraps, was linked to more than 60% of cases. Blood-sucking flies, ticks and other insects possibly spread the virus, as can contaminated premises, vehicles, equipment or clothing. Culling infected animals and imposing strict containment measures are the only tools available to limit its spread.

4. What’s China done?

By September 2019 roughly half the herd of more than 400 million pigs had been culled -- more than the entire annual output of the U.S. and Brazil combined. China also banned transport of live hogs and closed trading markets. Its hog population had returned to 90% of normal levels by the end of November, according to the agriculture ministry, and the disease was thought to be under control. But more cases were found in early 2021 in several provinces and on a farm in Hong Kong. The outbreak includes new variants that may be milder and harder to detect, casting doubt over the government’s goal of a full herd recovery by mid-year. The farm ministry has vowed to intensify a crackdown on illegal vaccines that have been linked to the emergence of new strains.

5. What’s the impact been?

Prices of pork, the principal source of dietary protein in China, spiked and are expected to remain elevated for some time. Meat consumption in 2020 fell to its lowest level in a decade, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which forecast in January that it would remain below previous levels for 2021 as well. Pork accounts for about a third of meat expenditure in Vietnam, which has also reported small flare-ups this year. The country’s hog population was 27.3 million as of the end of December, or 89% of the total recorded before the disease struck in 2019 and resulted in the loss of almost 6 million pigs. In eastern Europe, where African swine fever emerged in 2014 but on a much smaller scale, efforts continued to prevent its spread by wild boar, including in Germany.

6. Hasn’t this happened before?

Similar, but smaller in scale. In 2013, the rotting carcasses of more than 16,000 pigs — some of which were reportedly infected with a virus known as PRRS or blue ear — were found in tributaries of the main river running through Shanghai, threatening the region’s water supply. Millions of small piggeries were closed as part of a nationwide program aimed at shifting pork production to larger, more efficient farms. It resulted in one of the largest culls in history — a reduction in hog numbers equivalent to the disappearance of the entire U.S., Canadian and Mexican pork industries in less than two years. That came after a mysterious virus, later identified as blue ear, killed about 400,000 pigs.

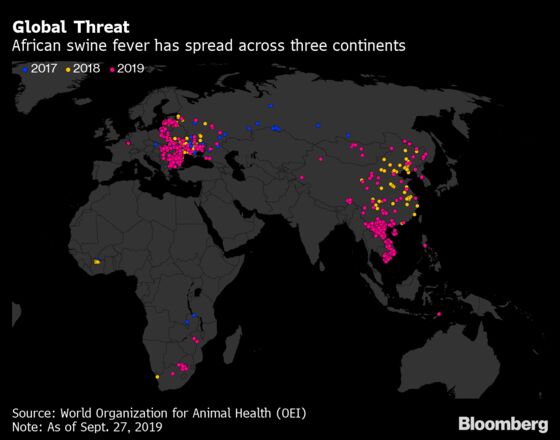

7. Where else has the disease shown up?

It’s endemic, or generally present, in sub-Saharan Africa and the Mediterranean island of Sardinia. Over the past several decades, the disease has emerged, and then been eliminated, in parts of Europe, the Caribbean and Brazil. Malaysia had its first ever African swine fever outbreak in February. In 2019 hogs were infected also in Mongolia, Cambodia, North Korea, Laos, the Philippines, Myanmar and South Korea. It’s been estimated that the introduction of the virus into the U.S. would cost producers more than $4 billion in losses.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Adam Minter looks at China’s history of food safety scandals, and David Fickling examines its food industry.

- The European Commission’s guidance on the disease.

- The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s African swine fever manual and situation update.

- The World Organization for Animal Health’s fact page.

- Five-Star Pig Pens: China’s strategy in the superbug war.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg