The Conflicts That Keep Turkey and Greece at Odds

The Conflicts That Keep Turkey and Greece at Odds

(Bloomberg) -- Turkey and Greece, NATO members that are also traditional rivals, have mobilized their navies and warplanes in opposition to one another in the Mediterranean Sea. The tensions are rooted in exploration for natural gas off the island of Cyprus, which is itself long a source of conflict between Greece and Turkey. Theirs is a history of troubles veering close to war three times in the past half century. Here’s a rundown of issues dividing them.

Cyprus

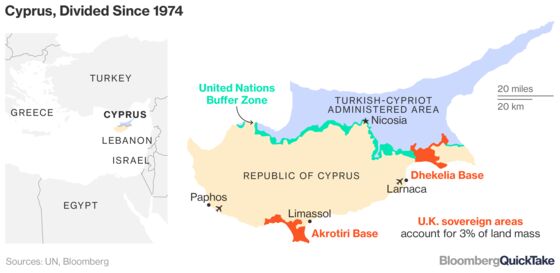

The Mediterranean island -- less than half the size of New Jersey -- was effectively partitioned in 1963 when fighting erupted between its two main groups: Greek and Turkish Cypriots. It was fully divided in 1974 after Turkey intervened, capturing the northern third of the island, saying it intended to protect the minority Turkish Cypriots following an Athens-backed coup by supporters of union with Greece. That brought the two neighbors close to war. To this day, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is recognized only by Turkey, while the Republic of Cyprus, which is internationally recognized, officially has sovereignty over the entire island but is only able to govern in the south. Turkey doesn’t recognize the ROC. Unification efforts have stalled. Adding new strains, the U.S. eased its decades-old arms embargo on the Republic of Cyprus in September, a move condemned by Turkey.

East Mediterranean

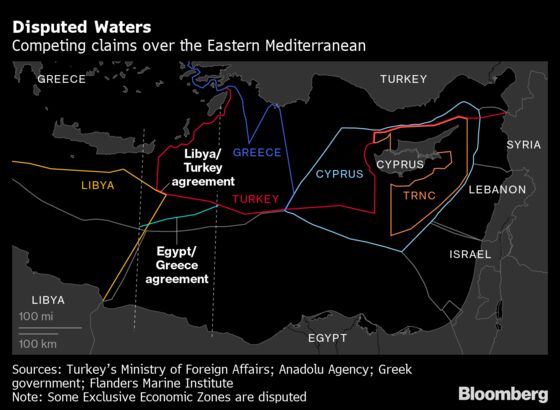

Tensions spiraled in 2020 as Turkey actively started searching for oil and gas in contested waters of the eastern Mediterranean, which has yielded substantial natural gas discoveries in recent years for Israel, Egypt and Cyprus. The disputes emerge from conflicting interpretations of maritime boundaries and the question of sovereignty in Cyprus.

Turkey doesn’t recognize Greece’s claim that its territorial rights are determined by the location of its many islands, some of them just off Turkey’s shore. Rather it argues that a country’s continental shelf should be measured from its mainland. Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, coastal nations can maintain an exclusive economic zone as far out as 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) from their coast where they’re entitled to fishing, mining and drilling rights. Where two zones intersect, the countries are obligated to reach a settlement. But Turkey hasn’t ratified the convention. It also takes the position that island states such as Cyprus are only entitled to rights within their legal territorial waters, which can extend to a maximum of 12 nautical miles. Meanwhile, the self-proclaimed Turkish Cypriot state claims rights to any energy resources discovered off the Cypriot coast.

Aegean Disputes

The island-dotted Aegean Sea has been the source of historical conflicts. Greece and Turkey reached the brink of war a second time in 1987 in a test of wills over the right to drill for oil. Tensions flared again in 1996 over the sovereignty of the uninhabited islet of Imia, or Kardak in Turkish. Today’s Aegean tensions focus on:

- Territorial water claims. Both Turkey and Greece claim territorial waters in the Aegean reaching six nautical miles from their coasts. Turkey’s parliament in 1995 authorized the government to use military force if Greece expands its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles in the Aegean. Turkey fears such action could restrict its access to international waters and deprive it of maritime resources. While Greece defends its right to make that move under the Law of the Sea, it hasn’t announced plans to do so.

- The Dodecanese Islands. These were ceded to Greece by Italy following World War II with a provision for their demilitarization. After images recently surfaced of Greek soldiers arriving in Kastellorizo -- the most outlying of the Dodecanese -- the Turkish government warned Greece against breaking force limits on the islands. Greece says it was merely carrying out a routine rotation of troops.

- Airspace. Greece claims a band of airspace stretching 10 nautical miles from its coastline while Turkey says the zone should be only six miles wide, corresponding to Greece’s territorial waters, and regards the rest as international airspace.

Minorities

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said that ethnic-Turkish citizens in the Greek part of the Thrace region face discrimination. Turkey also accuses Greece of closing dozens of Turkish schools in an assimilation campaign. In 2017, during the first visit to Greece by a Turkish head of state in 65 years, Erdogan demanded a revision of the Treaty of Lausanne, the 1923 pact that ended the conflict between the Ottoman Empire and WWI allies including Greece, France and the U.K. Turkey wants the revision to strengthen the rights of Muslims in Greece and resolve sovereignty disputes in the Aegean. Greece denies that it discriminates against its Muslim minority. It says Erdogan isn’t in a position to lecture on such issues because Turkey shut down a Greek Orthodox theological school in 1971 under a law that put religious and military training under state control, and because more recently he turned Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, built as a Byzantine cathedral and functioning as a museum in recent decades, into a mosque.

The Reference Shelf

- Related Quicktakes on tensions over Mediterranean gas fields, Turkey’s expanding military footprint and the Cyprus conflict.

- An article in Global Security examines the Turkish-Greek dispute over the Aegean Sea.

- A Congressional Research Report on Eastern Mediterranean tensions.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.