Switzerland’s People Power

Switzerland’s People Power

(Bloomberg) -- Attention disgruntled citizens: If you feel no one’s been listening to your concerns, Switzerland’s got a strategy for you. The Swiss system of ballot initiatives allows voters to have a direct say on topics such as immigration, executive pay and funding for health care. People power is on a roll, with voters approving measures to limit an influx of foreigners and let shareholders block executive bonuses. While others have failed — including a proposal for the central bank to hold a fifth of its assets in gold — government policy is regularly determined by the outcome of plebiscites. Switzerland’s direct democracy has brought populist politics to the home of multinational corporations such as Nestle SA and Novartis AG, along with warnings that it could undermine the stability that has been key to the country’s prosperity.

The Situation

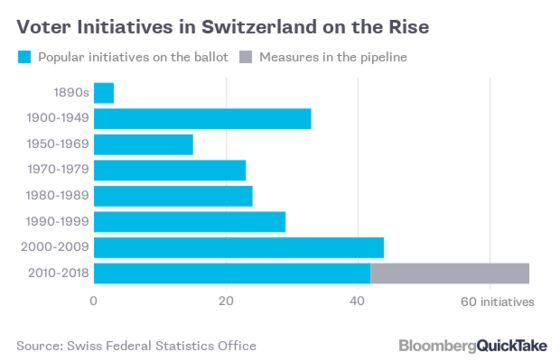

There’s been a surge of ballot initiatives: more than 75 since 2000, and there are about two dozen in the pipeline. That’s more than all the ballots in the 80 years after they began in 1891. A controversial measure to expel foreigners convicted of crimes was shot down in 2016, as were initiatives to provide a basic income and cut the pay of executives at state-controlled companies. Historically, the Swiss have backed free enterprise. Yet in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, when Switzerland bailed out its largest bank, UBS, voters are taking a more skeptical view of big business. They overwhelmingly approved what became known as the “fat cat” rule in 2013, giving shareholders in Swiss companies a binding vote each year on executive pay. They opted to curb the number of newly arriving foreigners in 2014, despite warnings from companies about hurting the economy. Among the measures rejected was a proposal to cap executive salaries at 12 times the earnings of the lowest-paid employee and a minimum wage of 22 francs ($22) per hour, which would’ve been the world’s highest.

The Background

A plebiscite on almost any topic can be called by collecting 100,000 signatures from citizens among Switzerland’s 8.4 million people. About a quarter of the country’s residents aren’t citizens. The system allows for national votes, held four times a year, that are legally binding. There are also municipal ballot measures. The national polls can change the constitution or cancel a recently passed law via a referendum (which requires only 50,000 signatures to make the ballot). Turnout averages between 40 and 50 percent, though it’s sometimes higher for controversial measures. In comparison, the U.S. does not permit national initiatives, but individual states have used them to push through contentious changes such as the legalization of marijuana and gay marriage. Critics say ballots in California — which require signatures from roughly the same share of the population as Switzerland — have made the state ungovernable, since tax revolts such as Proposition 13 have limited its ability to produce timely budgets.

The Argument

Supporters of the ballot measures argue that the votes return power back to the people. While the system wins praise outside the country for giving voice to popular issues, the boom in initiatives has been met with skepticism at home. Critics say splinter groups are abusing the process, wasting government resources and fostering disillusionment. The votes could undermine the country’s consensus-based political system, where the presidency is rotated each year among the government’s seven ministers, or enable a “tyranny of the majority” that restricts the rights of minorities. Many of the proposals have been championed by the Swiss People’s Party, the biggest in parliament, which opposes a concentration of federal power. The government and multinational companies say referendums could damage the economy. The plebiscites could also tarnish neutral Switzerland’s relations with its neighbors, they say, citing the immigration vote and a 2009 ban on the construction of minarets. Once passed, the measures require politicians to amend domestic legislation. That can prove tricky, as the initiatives can conflict with existing national and international laws.

The Reference Shelf

- A Q&A on the Vollgeld plebiscite June 10.

- The Swiss government’s interactive guide explains how direct democracy works, along with its 2018 handbook on political institutions.

- The Swiss statistics office has an interactive political atlas showing how people in various cantons voted.

- An e-book explaining how government in Switzerland works.

- A Swiss government list of initiatives that have come up for national vote over the last century.

- The website of the Initiative & Referendum Institute Europe has more on initiatives and referenda on the continent.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Leah Harrison at lharrison@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.