Sustainable Investing

Sustainable Investing

(Bloomberg) -- Companies traditionally have been held accountable for one bottom line: profit. A growing number of so-called sustainable investors want two more measures: social and environmental impact. Skeptics say that advancing these broader and less well-defined goals is not the proper role of business. Whatever one thinks of the idea, gauging the social and environmental effects of any business is much harder than measuring how much money it’s made or lost. Accounting efforts are improving, however.

The Situation

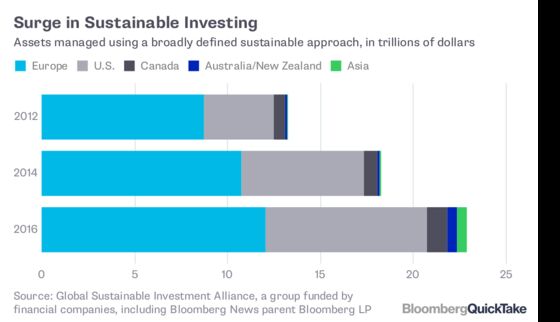

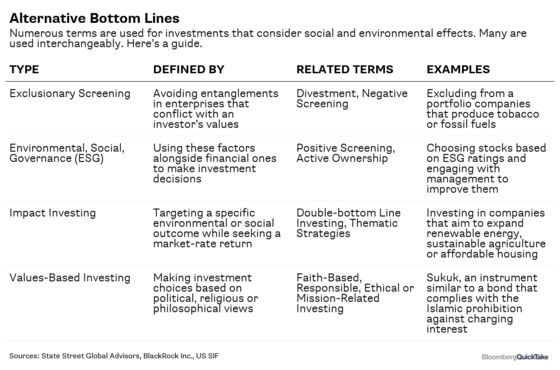

Sustainable investing goes by many names and encompasses a number of overlapping trends — among them values-based, socially responsible and impact investing. Assets managed using a broad definition of the approach reached $23 trillion at the start of 2016, a 73 percent increase from four years prior, according to a report funded by a group of financial companies, including Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP. In Europe, the largest market, the number reached $12 trillion. Some of these investors expect companies to be agents of social change, through the promotion of diversity, for example. Some stress robust corporate governance on issues such as executive compensation. Of rising interest are environmental matters like a company’s carbon emissions, water use and plastic waste. Consumers, too, increasingly care how companies conduct themselves in these areas and say they are willing to pay more for brands promoting a positive record. Of the world’s largest 250 companies, 92 percent reported in some way on their social and environmental impact in 2015, according to one survey. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange was the first entity to require companies to include such factors in their financial reporting, in 2010. A similar rule that took effect in the European Union in 2017 affects about 6,000 large companies. The market for green bonds — instruments issued by corporations, governments and financial institutions to fund environment-friendly activities — surged to $170 billion in 2017. That marked the seventh record-breaking year, though green bonds, by value, represented only about half a percent of all bonds issued in 2017.

The Background

Church-affiliated organizations in Sweden began the first ethics-based mutual fund available to retail investors in Europe in 1965. The Pax World Fund began in the U.S. in 1971. In the following decades, the racial segregation of South Africa’s apartheid policies sparked one of the first global divestment movements. A modern campaign focuses on divesting from fossil-fuel producers. Today’s civic-minded investors have gone beyond screening out companies to choosing those that support their values. Many believe that companies with social and environmental objectives minimize certain vulnerabilities, such as the risk of lawsuits from employees or toxic spills, and look for these goals as predictors of performance. The U.S. Department of Labor in 2015 revised its guidelines to allow pension funds to consider social impact in their investments, saying it wouldn’t necessarily compromise a fund’s legal duty to act in the best interests of plan participants. But the advice was modified in 2018 to say such investments aren’t always a “prudent choice” and shouldn’t “too readily” be considered by fund managers.

The Argument

Legendary investor Warren Buffett has pledged to give his fortune away but has said social-impact agendas in business force executives to pursue a confusing array of goals. Free-market guru Milton Friedman decried them in a 1970 essay that’s still debated today. When executives spend company money on a social agenda, he said, the cost is passed on to stockholders, consumers or employees. In effect, he argued, they’re taxing these individuals and deciding how to spend the proceeds, which is what elected government is for. Advocates of sustainable agendas dispute the premise that there must be a cost. They cite studies in which companies with such goals financially outperformed companies without them, though researchers face a challenge proving it was the strategy that created better results. There are reasons why doing good can lead to doing well. Investments in energy efficiency can save money; philanthropic programs can motivate staff; community outreach can aid recruitment. In any case, better information is needed to determine how companies perform on non-financial goals. In the absence of common standards, many investment funds now promoted as sustainable contain stock in big oil and tobacco companies. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, until 2018 chaired by Michael R. Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, has published proposed metrics for 79 industries. Metrics for airlines, for example, include “total fuel consumed, percentage renewable.” Companies including JetBlue Airways Corp. and General Motors Co. have recently started reporting using this format.

The Reference Shelf

- A related QuickTake on the climate divestment movement.

- Ronald Cohen, chairman of the Social Impact Investing Taskforce, discusses impact investing at Stanford University.

- The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board provides updates on the accounting metrics it has developed.

- The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance annual report describes the state of the field.

Emily Chasan and Leonard Kehnscherper contributed to this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Lisa Beyer at lbeyer3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.