Student Debt

Student Debt

(Bloomberg) -- In terms of American exceptionalism, student loan debt stands out. No other country imposes the kind of costs on college and university students that the U.S. does, and nowhere else do loans cover so much of those costs. Experts think that the roughly $1.5 trillion in outstanding education debt in the U.S. is more than that of the rest of the world combined. Undergrads at U.S. public and nonprofit colleges who borrowed and left school in 2016 had an average debt of $28,650. It’s a situation that educators, consumer advocates and members of both political parties all decry. Agreement on solutions is harder to find. In the meantime, young adults are delaying setting up their own households in the face of a mountain of debt. Recent studies also show a growing economic divergence between young Americans with and without student loans. There’s widespread agreement as to who is worst off: college dropouts. They’re stuck with debt but without the higher earnings a degree might have brought to help pay it off.

The Situation

President Donald Trump, a Republican, and the Democrats hoping to be his opponent in the 2020 election have laid out programs for reducing student debt. Trump in March proposed capping the amount of federal loans graduate students can take on, while Democratic candidates have instead focused on reducing the cost of college by raising wealth taxes and increasing government subsidies to higher education institutions with the proceeds. Senators Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris have all pledged to eliminate tuition and academic fees for public colleges. Sanders and Warren have also called for using tax increases aimed at the affluent to cancel most existing student debt. Under President Barack Obama, the Education Department sharply expanded programs in which struggling ex-students make payments calculated as a percentage of income and at the end of 2018, about 8 million borrowers benefited from income-based repayment plans. Some schools such as Purdue University in Indiana have also offered income-share agreements, where students pay a percentage of their income for a fixed period of time in lieu of a loan.

The Background

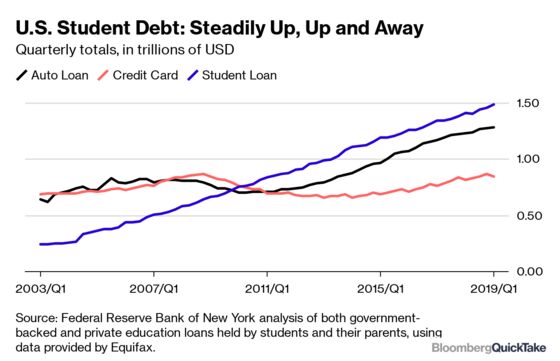

When the U.S. federal student-loan program began in 1965, its goal was to give students reliable access to funds that would help them get through college by deferring some of its cost until they had an income. Most loans were paid off in a few years, while the benefit of the degree lasted a lifetime. As the cost of college raced ahead of inflation, the federal loan program morphed into something larger and different. Commercial banks also ramped up their higher-interest lending for those whose needs exceeded the caps on federal loans. The biggest growth in the program came in the past decade, as student debt rose from $364 billion in 2004 to $1.2 trillion 10 years later, according to New York Fed data. After July 2010, the government cut out banks as middlemen in the federal loan business. Much of the savings was used to increase college grants, but some went to reduce the budget deficit.

The Argument

Is the problem the loans or the cost of college the loans help students cover? A common criticism of proposals like those from the Democratic candidates is that they don’t address the root problem of above-inflation tuition hikes. Making it cheaper to borrow, that argument goes, only makes it easier for schools to raise fees. Democrats respond that making college affordable is necessary to fight inequality and spur economic growth. The proposals by Sanders and Warren to use tax increases to wipe out existing debt added a highly contentious new aspect to the debate; conservatives called Warren’s plan “a slap in the face” to graduates who had managed to pay off their loans. One step supported by both Republicans and Democrats is giving students more information about their loans. When students at Indiana University were told how much they would owe after graduation, undergraduate borrowing dropped by $31 million in one year. Calls for free college, however, may be more complicated in practice than the idea sounds: New York was the first state to introduce a tuition-free public college program beginning in 2017, but a report one year in found that relatively few eligible students were able to use it, in part because it required a heavy course load.

The Reference Shelf

- A Congressional Research Service “snapshot” of federal student loan debt.

- A report by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on household debt and credit.

- Resource pages from the U.S. Education Department and Consumer Financial Protection Board.

- A report by the Pew Research Center on student debt default.

- A study by Summer.org, a non-profit, on the state of student borrowers.

- An Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development survey of support for higher education.

- A Bloomberg News series on “ Indentured Students” was awarded the 2012 George Polk award for national reporting.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: John O'Neil at joneil18@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.