What We Learned From the Work-From-Home Experiment

Pre-pandemic studies found people were as efficient at home as in offices — more so, since some sign on earlier and stay later.

(Bloomberg) -- When the pandemic shut offices around the globe, white-collar workers everywhere got a crash course on the pitfalls and benefits of working from home. The debate over whether employees perform as well at the kitchen table as they do in the workplace has raged ever since technology first made such a shift possible. The monthslong lockdowns served as an illuminating, if unplanned, experiment — one that seems certain to make toiling from home a bigger part of life for most office workers and even the daily norm for many.

1. How did workers adapt?

The share of Americans working from home doubled in a matter of weeks to 62% in April, according to a Gallup poll. With schools shut, parents struggled to combine work with remote learning. Workers fired up videoconferencing and collaboration tools such as Slack. The novelty quickly wore off for some as longer workdays became the norm (three hours extra in the U.S., according to one report). But the flexibility appealed to many.

2. Is working from home here to stay?

It looks that way, at least for some professions. Well-known companies including Twitter, Facebook and Swiss bank UBS said the switch could become permanent for a third or more of their staff. Surveys showed that a majority of people didn’t want to rush back to the old routine, even when it’s safe to do so. Just one-third of office workers in Germany, France and the Netherlands want to return to the desk full time, according to a survey of 6,000 people released in May. Lockdown gave people a chance to reimagine their work-life balance. Many were surprised to discover that ditching the commute increased productivity, lowered stress and promoted a healthier lifestyle.

3. How sustainable is this?

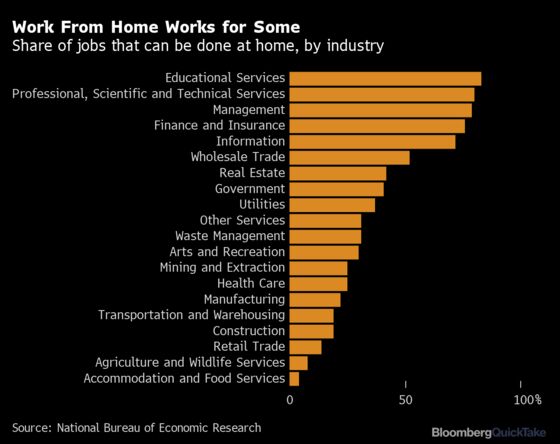

About 40% of jobs in the U.S. can be done entirely from home, according to an April analysis published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. (That includes teaching, which, the report points out, was generally not thought possible before the pandemic.) There’s been a tendency to lowball what is feasible. Verizon Communications Inc. initially projected about 45,000 of its 120,000 U.S. workers would be able to work from home. By April the actual number was 115,000. What’s become known as “WFH” is not an option in many blue-collar professions such as construction and agriculture and in lower-paid services such as restaurants and retail — another reality highlighted by the pandemic. The disparity played out on an international level, too: NBER researchers found more than 40% of workers could do their jobs from home in the U.K. and Sweden, compared with less than a quarter in Mexico and Turkey.

4. What about regulated workplaces such as finance?

Initial concerns that home computers would struggle to handle the software and data needed to execute securities trading proved overblown. The big test came in March, when markets plunged and trading surged. While nothing can match the buzz of a noisy trading floor, banks were still able to generate billions of dollars in transactions. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. had 98% of staff working remotely, while JPMorgan Chase & Co. put its number at 70%. There was some wrangling by compliance departments to monitor calls and computer traffic for potential misconduct, and firms sought to maintain enough on-site traders to ensure operations functioned properly.

5. Are remote workers productive?

Pre-pandemic studies had already found they were as efficient as people in offices — maybe more so, since some sign on earlier and stay later. Reports of productivity bumps during lockdown were common. One study by software maker Prodoscore Inc. found a gain of 47% from a year earlier, as employees made more calls, initiated more chats and sent more emails — all while scheduling fewer meetings. There was a cost, however. One survey found that 45% of workers said they were burned out by increased workload, juggling personal and professional life and lack of support from their employer.

6. How will this change things?

Breaking the spell of the office means workers can opt to move to less expensive areas. Facebook said it embraced the shift in part because it will widen the talent pool for potential hires from anywhere, though staffers who leave its California base might see their pay cut to align with local norms. Companies can give up real estate; JPMorgan, Barclays and Morgan Stanley have all said they might reduce office space and ask employees to work remotely more often. Some executives worry that a broad move to remote working risks losing some of the camaraderie, collaboration and creativity fostered in face-to-face encounters. A possible compromise: splitting the workweek between home and office.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Tae Kim explains why some executives aren’t so sure about remote work.

- Europe’s time-starved traders want to keep working from home.

- In boom-and-bust San Francisco, companies are retooling office space for fewer workers.

- Traders create the ultimate work-from-home “rona rigs.”

- Engineer Jack Nilles gave birth to telecommuting in his 1973 book “The Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.