Private Equity

Private Equity

(Bloomberg) -- They own the gym, the pet shop and maybe even your dentist’s office. They might be selling you electricity or operating the hotel in your town. No matter where you live, companies that are part of your daily life have likely been taken over by private equity firms. Once hidden in the shadows of global finance, the industry has quietly amassed a portfolio valued at more than $4 trillion, emerging as a stealth force shaping how capitalism plays out around the world. The billionaire owners of these firms say they’re making money by building healthier corporations, often rescuing them from the vagaries of poor management or likely failure. They shake things up by restructuring operations, repositioning products or reaching for new markets. But in the process, they can sometimes strip companies bare — closing stores and factories and firing workers, all while earning fees for themselves and big returns for their clients. To critics, private equity firms are “vampires” or “locusts,” loading companies up with debt, exploiting regulatory loopholes and exacerbating inequality.

The Situation

Investors have poured money into private equity, with the likes of Blackstone Group and Apollo Global Management LLC each raising more than $20 billion in single funding rounds since 2017. The industry’s pile of so-called dry powder — committed, uninvested capital — reached a record $1.7 trillion. All that money has fueled expanding ambitions. After starting off with unloved units of large corporations, the firms are now taking over dental chains and amassing holdings of single-family homes. Household names such as J.Crew, Hilton and Dell have all received private equity backing, while the big U.S. funds have reached overseas to suck up real estate in Spain and brewers in Japan. Local private equity firms have also sprung up around the globe. The industry has presided over dramatic turnarounds as well as spectacular failures. The 2017 collapse of Toys “R” Us, one of the largest retail bankruptcies of all time, was blamed in part on the crushing debt load engineered by its trio of private equity owners. The loss of more than 30,000 jobs shined a light on the industry and helped to renew calls to rein it in. One target is the so-called carried interest benefit, which enables private equity firms to pay lower taxes by classifying their earnings as capital gains rather than ordinary income.

The Background

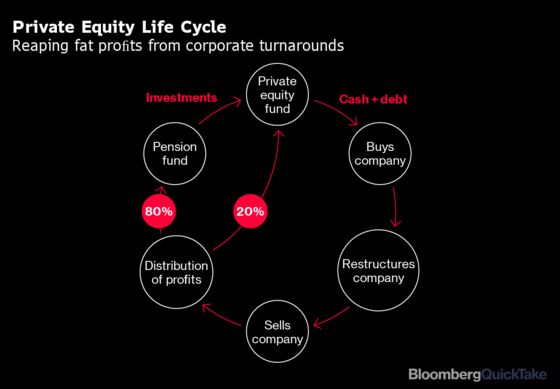

Private equity emerged from the leveraged buyout wave of the late 1970s and 1980s, when dealmakers began to use large amounts of debt to amplify their own money. The basic technique is to buy a public company and take it “private” by borrowing money and pairing it with cash, or “equity,” to fund the takeover. The operations can then be turned around away from the quarter-to-quarter glare of stock markets. The strengthened company is later resold, often through an initial public offering, reaping what can be huge profits. Over the last two decades, buyout artists amassed money from pension funds and endowments eager for the double-digit annual returns they could deliver, making private equity an alluring asset class in an environment of low interest rates and paltry returns on other investments. Like hedge funds, the firms use a so-called 2-and-20 fee structure, earning an annual 2% management fee on their pot of assets and keeping 20% of profits. Unlike hedge funds, which trade individual securities on a daily, sometimes second-to-second basis, private equity funds typically hold the companies they buy for years. The billionaire owners of the firms have emerged as global power brokers, with Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman and KKR & Co.’s Henry Kravis counseling leaders from U.S. President Donald Trump to China’s Xi Jinping.

The Argument

Many private equity takeovers are success stories: Blackstone’s buyout of Hilton returned the iconic hotel brand to glory, while KKR saved retailer Dollar General, a vital part of many rural U.S. communities. But the industry’s sheer economic might has attracted ire, and its techniques can bring what’s known as the “creative destruction” of capitalism into high relief. Some studies have shown that takeover targets shed jobs at a faster rate than similar firms, but then hire workers faster when the company is returned to health. Some lawmakers argue that private equity firms are exploiting a loose regulatory regime. U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren, who’s vying to be the Democratic Party’s nominee to run against Trump, attacks the firms as “vampires” that bleed companies dry to generate profits for wealthy owners. Her populist pitch includes plans to make the firms responsible for the debts and retirement obligations of the companies they buy, while limiting their ability to pull money out or insulate themselves from losses. Others seek reform from within: Some pension funds are pushing for lower fees and more transparency in an effort to better align interests and ensure a fair division of profits and risk.

The Reference Shelf

- “ The New Tycoons: Inside the Trillion Dollar Private Equity Industry That Owns Everything,” a book by Bloomberg’s Jason Kelly.

- U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren’s plan to strip private equity of its riches.

- Businessweek on the collapse of Toys “R” Us and the private equity industry’s annual conference.

- A report on what academic research tells us about the private equity’s impact on the economy, from accounting firm EY and the Institute for Private Capital, an industry and academic group.

- Bloomberg Opinion on how to fix private equity.

- QuickTakes on the carried interest tax benefit, the buildup in dry powder and the boom in private credit.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Leah Harrison at lharrison@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.