Refugees and Asylum

Refugees and Asylum

(Bloomberg) -- The United Nations has declared asylum to be an inalienable human right, and most countries offer it. The principle is that nations should safeguard people who face persecution or danger when their own countries can’t or won’t protect them. There have long been debates over who deserves sanctuary, but today the discord goes deeper. In the wake of violence in the Middle East and Afghanistan and parts of Africa and Central America, the number of people seeking asylum has risen to record levels. While the bulk of them are hosted by neighboring countries, a crackdown on refugees in the U.S. and Europe is raising questions about whether support for the concept of asylum can survive.

The Situation

The number of total refugees has steadily increased since 2012, to 19.9 million by mid-2018, fueling antipathy toward outsiders in some host countries. Of the 1.9 million new applicants for refugee status in 2017, the U.S. had the largest number — 332,000, with 43 percent coming from Central America, where gang violence has become widespread. U.S. President Donald Trump has coupled his bid to clamp down on immigration with an effort to fundamentally reshape the nation’s asylum system. He barred entry to the citizens of six countries, five of which are mostly Muslim, and slashed the number of refugees that can be admitted to the U.S. to 30,000, an historic low. His administration ruled out asylum for people fleeing domestic and gang violence. It also excluded those who illegally crossed the U.S. frontier with Mexico, although a federal judge Nov. 29 temporarily halted enforcement of that policy. Under Trump, the U.S. began detaining everyone caught unlawfully crossing the border, including those seeking refugee status. Parents were separated from their children, prompting a public outcry that led Trump to backtrack. In October, Trump threatened to cut off foreign aid to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador in retaliation for a so-called caravan of migrants traveling through Mexico toward the U.S. In the European Union, resentment over the influx of refugees led leaders to consider creating holding centers, probably in Africa, to handle asylum seekers. Officials discouraged groups from rescuing such people in the Mediterranean Sea. Hungary, led by populist Prime Minister Viktor Orban, made it a crime to help migrants seek asylum.

The Background

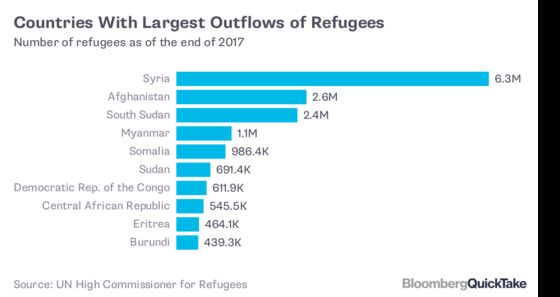

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees says the concept of asylum is one of the “earliest hallmarks of civilization,” citing references to it in 3,500-year-old texts. The word comes from the ancient Greek term for freedom from seizure. A 1951 UN convention on the status of refugees and its 1967 protocol are the modern legal framework for asylum, defining refugees as people who can show they’ll be persecuted at home based on race, religion, nationality, political conviction or social group. Agreements in Europe, Africa and South America expanded the definition to include those fleeing generalized violence. Among today’s refugees, Syrians form the largest group. They are fleeing civil war, like the Afghans and South Sudanese who make up the next-biggest groups. Victims of persecution include Christians escaping forced conversion to Islam in Arab countries and the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic group in Myanmar fleeing the abuse of their Buddhist compatriots. Asylum applications worldwide totaled 1.9 million in 2017. The U.S. had the most new applicants, with 43 percent coming from Central America. In 2017, some 732,500 asylum applications were accepted and slightly more — 754,100 — were rejected globally. Asylum has been used as a political tool, as when Americans welcomed Cubans and Vietnamese seeking refuge from communism. Requests for safe haven from gay, bisexual and transgender people have increased in recent years.

The Argument

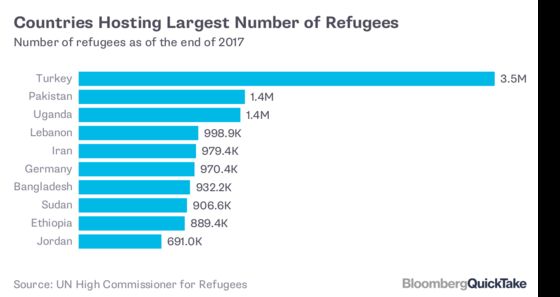

Attacks in Europe and the U.S. by killers linked to or inspired by foreign jihadist groups have engendered fear that future terrorists lurk among those requesting sanctuary. Critics of pro-asylum policies also worry that taking in refugees can lead to higher crime and unemployment rates. Trump administration officials have argued that the asylum system is abused by fraudsters. Other critics of U.S. asylum judgments say they are so arbitrary they amount to “refugee roulette.” That has promoted the development of a cottage industry of sorts to provide haven seekers with compelling personal narratives that can be exaggerated or false. Defenders of the vetting process say it is rigorous, even if no system is foolproof. Asylum advocates stress the universal obligation to protect the vulnerable and note that many of the people that nationalists such as Trump would keep out are themselves fleeing terrorism. The debate over asylum in the U.S. and Europe can overshadow the fact that the burden of hosting the world’s refugees falls more on poorer countries closer to major conflicts, such as Turkey, Pakistan and Uganda.

The Reference Shelf

- A report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development examines trends in asylum requests.

- The office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees helps evaluate asylum claims and publishes periodic reports.

- The International Journal of Refugee Law offers free abstracts and paid access to full articles.

- A U.S. Congressional Research Service report discusses U.S. refugee policy.

- An overview of asylum and the rights of refugees from the International Justice Resource Center.

- A related QuickTake on Europe’s refugee crisis.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Lisa Beyer at lbeyer3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.