Philippines’ Firebrand

Philippines’ Firebrand

(Bloomberg) -- Take more than 7,600 islands, add 100 million people, throw in a twist of corruption, an unhealthy slug of poverty and a dab of dynastic politics and what do you get? A recipe for disaster, you might think. Yet the Philippines has been simmering nicely enough as a developing democracy since the overthrow of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. Recent years have been marked by relative stability and economic growth that’s outpaced most of Southeast Asia. But the Philippines veered onto another course in 2016 when voters turned to Rodrigo Duterte, a fiery populist who has waged a deadly war on drugs and scrambled the country’s international loyalties.

The Situation

Duterte has lived up to his tough-man image, and then some. His anti-drugs campaign has claimed thousands of lives — many by vigilantes — and resulted in human rights abuses. He placed the southern island of Mindanao under martial law for more than two years in response to violence involving militants linked to Islamic State. Yet his approval ratings have remained strong and his allies gained seats in midterm elections in 2019. The former Davao City mayor was elected on an anti-corruption platform, and he has cracked down on some of the Philippines’ biggest businesses, renegotiating contracts and forcing concessions for taxpayers. But Duterte, 74, and his family have been dogged by accusations of hiding about $19 million in undeclared wealth, which he denies. His son Paolo, who represents Davao City in Congress, has denied involvement in a drug-smuggling case. Duterte does not take kindly to criticism and has issued expletive-laden or crude ripostes to the Pope, the European Union and former U.S. President Barack Obama. He’s even called God “stupid.” He has pulled the Philippines out of an international court investigating his drug war and shuffled the country closer to China and Russia and away from the U.S., its main ally since the 1950s. His harshest critic, Senator Leila de Lima, has been jailed since 2017 on drug charges that she calls politically motivated. He has also attacked the media, including prominent journalist Maria Ressa, who’s facing several court cases.

The Background

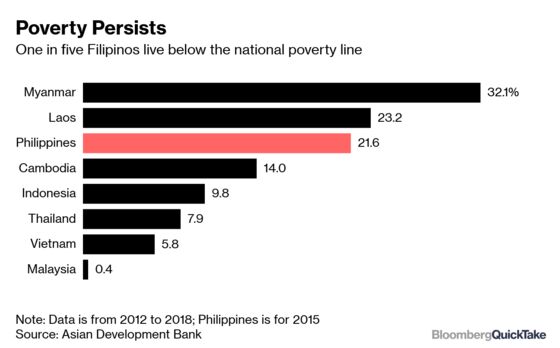

After centuries of Spanish and U.S. rule, the Philippines became a democracy after World War II ended Japanese occupation. Multiple parties compete in a political climate focused on personalities and dominated by powerful dynasties. Duterte’s predecessor, Benigno Aquino, is the son of former President Corazon Aquino, whose People Power Revolution ended Marcos’s more than 20-year rule. The Marcos era was marked by brutality — an estimated 3,000 people were killed and 35,000 tortured — and by extravagance epitomized by his wife Imelda’s shoe collection and a $25 million stash of artwork. It also left a legacy of widespread corruption. Even so, the economy began to build momentum in the 2000s. The World Bank praised the Philippines as Asia’s “rising tiger” in 2013 as the country earned its first-ever investment-grade credit rating. Duterte vowed to continue the investment-heavy economic policies of Aquino, who was limited to one term under a post-Marcos law. Even with the economic gains (the country secured another credit rating upgrade in 2019), more than a fifth of the population remains in poverty, partly because of regular natural disasters, including the devastating Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 and a volcanic eruption in January.

The Argument

Duterte’s critics see him as possibly the biggest menace to democracy since Marcos. He is limited to one term, which expires in 2022. His daughter, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte, is seen as a possible successor. (Intermittent health issues have led to speculation that he might not complete his term. Vice President Leni Robredo, the opposition leader, would take over in that case.) On the international stage, Duterte has brushed off charges that he’s undermined Philippine sovereignty in opening the doors to Chinese investment, with little to show in return, saying close ties with the U.S. and Europe had failed to produce material gains. Xi Jinping became the first Chinese president to make a state visit in 13 years, signing a framework agreement to jointly develop oil and gas resources in a disputed part of the South China Sea. But the conflicting territorial claims there remain an irritant for the Philippines. Other challenges for the president include Manila’s gridlocked traffic, which Duterte promises to solve with a promise of a “golden age” of infrastructure; underemployment that puts 14% of workers with advanced degrees in low-skill jobs; and the migration of educated Filipinos overseas.

The Reference Shelf

- Mid-term elections bring unexpected winners and losers for the Philippine economy.

- Human Rights Data Analysis Group has developed a statistical model to count drug-related killings in the Philippines.

- A Philippine Political Science Journal study on Philippine dynasties.

- QuickTakes on Duterte’s deadly drugs war, and how he could cut U.S. military ties.

- A report by Human Rights Watch and another from Amnesty International on the drug war.

- A BBC story on the vigilantes who are killing drug dealers.

- A government website set up to retrieve missing art from the Marcos collection.

- Bloomberg News stories examine the transformation of Duterte’s hometown, Davao City, and how the president has taken on the country’s elite.

Norman P. Aquino contributed to the original version of this story.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.