Oil for Less Than Nothing? Here’s How That Happened

Oil for Less Than Nothing? Here’s How That Happened

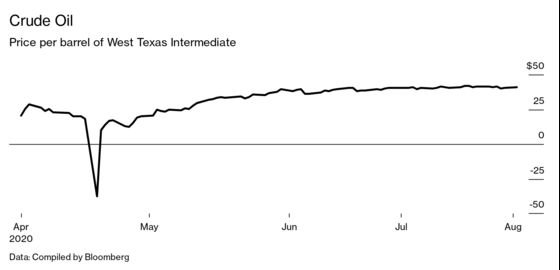

(Bloomberg) -- April 20, 2020 will go down in oil-market history as the day when the U.S. benchmark price for crude dropped below zero for the first time -- and then kept tumbling. In a massive and unprecedented swing, the future contracts for May delivery of West Texas Intermediate fell to minus $37.63 a barrel. The jaw-dropping development partly reflected chronic oversupply in the aftermath of a crude price war and slumping demand caused by the coronavirus, but also came about because of an extreme glitch in the way U.S. oil futures operate.

1. Why would anyone pay to sell their oil?

For some producers, it may be cheaper in the long run than closing down production or finding a place to store the supply bubbling out of the ground. Many worry that shutting their wells might damage them permanently, rendering them uneconomical in the future. Then -- crucially for the plunge into negative prices --- there are the traders who buy oil futures contracts as a way of betting on price movements who have no intention of taking delivery of barrels. They can get caught by sharp price drops and face the choice of finding storage or selling at a loss. Or they can make a fortune by exploiting the idiosyncrasies of futures contracts. The escalating glut of oil also made storage space scarce and increasingly expensive.

2. Where did the glut come from?

Either the pandemic or the price war alone would have rocked energy markets. Together, they turned them upside down. As the virus started to spread around the globe, it began eating away at oil demand. But just as countries like Italy showed what kind of damage a national lockdown could do economically, Saudi Arabia and Russia, the world’s biggest oil producers, escalated the price war. A pact that had restrained production collapsed and both countries opened their taps to the fullest, releasing record volumes of crude into the market. When a deal was worked out by OPEC, Russia, the U.S. and the Group of 20 countries, it proved to be too little, too late. Prices initially turned negative just in obscure corners of the U.S. market such as Wyoming, where storage options are few. Then major hubs began to register negative prices for small streams of selected crudes. And on April 20, prices fell sharply below zero on the NYMEX exchange, which is owned by CME, the world’s largest energy market.

3. What did futures contracts have to do with that?

The lowest prices came in trades in futures -- contracts in which a buyer locks in a purchase at a stated price at a stated time. Futures are a tool for users of oil to hedge against price swings, but also a means of speculation. The contracts run for a set period, and traders who don’t want to unwind their position or take delivery generally roll over their monthly contracts shortly before expiration to a month further in the future. Contracts for May delivery were due to expire on April 21, putting maximum pressure the day before on traders whose contracts were coming due. For many, selling at a steeply negative price was better than taking delivery of actual oil because nobody needs it and there were fewer and fewer places to put it.

4. Why did prices plunge so precipitously?

That was partly because of surging bets by retail investors that oil prices would rebound. To understand why, Nymex offers a corollary instrument called Trading at Settlement, or TAS, in which buyers and sellers agree to transact at whatever the settlement price -- determined by trades in the last two minutes of trading -- turns out to be. The TAS market is popular among exchange-traded funds and other funds whose mandate is to track the price of oil rather than to get the best deal. Expecting oil prices to recover, retail investors across the U.S. and Asia had been piling into ETFs whose value was pegged to the April 20 settlement price -- meaning funds such as the Bank of China Ltd.’s Treasure needed to roll over large numbers of May contracts and buy June ones. As they sold in the TAS market on April 20, the oil price tumbled, losing $40 in an hour. One group of London traders was said to have made hundreds of millions of dollars by buying contracts in the TAS market while selling regular contracts, thereby adding to downward pressure on prices, and pocketing the difference at the end of the day.

5. What happened to other oil prices?

Brent futures, the global benchmark, ended April 20 down sharply but still above $25 a barrel. The physical domestic crude market in the U.S. saw negative trades for grades like WTI in Midland, Mars Blend, Light and Heavy Louisiana Sweet crudes. Horrified by negative benchmark prices, some U.S. oil producers began offering crude at fixed prices for the first time since an oil rout in 2014-15. The WTI futures contract for June delivery changed hands at $20 a barrel on April 20 before falling further the next day -- highlighting the extent to which the rout was being caused by the glut in the market rather than just a technical quirk. U.S. producers started pulling back where they could, causing a slide in output. The number of rigs drilling for oil and gas plunged in the U.S. and globally. At the same time, many exchange-traded funds got out of trading in the most volatile part of the curve, the front-month contract, and brokerages limited speculative positions for retail customers. Then in May, lockdown measures started easing, leading to a recovery in oil prices. The WTI front-month contract, which had fallen to $18.84 on April 30, recovered to $35.49 at the end of May and $39.27 at the end of June. By end-July it had climbed to $40.27 a barrel.

6. What happened to storage?

After the glut began to build and prices began to fall, storage facilities moved toward capacity. Crude stockpiles at Cushing in Oklahoma -- America’s key storage hub and delivery point of the WTI contract -- jumped to 65 million barrels by the start of May. The hub had working storage capacity of 76 million as of Sept. 30, according to the Energy Information Administration. The industry accumulated supply aboard ships, while contemplating other creative options such as storing oil in rail tanker cars. The Trump Administration, which is concerned about the possible ripple effect from oil bankruptcies, eyed a proposal to pay drillers to keep their oil in the ground temporarily. It also opened up its strategic petroleum reserve to allow companies to lease storage space. Some of that is starting to be returned as storage space constraints ease.

The Reference Shelf

- Peter Coy of Bloomberg Businessweek ties the oil market turmoil to “inelasticity.”

- The CME Group’s introduction to oil futures page.

- A QuickTake on the uneasy truce in the price war.

- What happened when Tracy Alloway of Bloomberg News tried to buy an actual barrel of crude oil.

- A story on how London traders hit a $500 million jackpot when oil went negative

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.