Nuclear Weapons

Nuclear Weapons

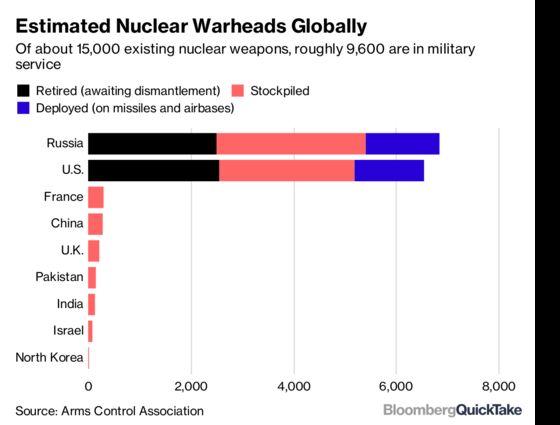

(Bloomberg) -- Half a century after world powers agreed to thwart the spread of nuclear weapons and reduce their own arsenals, both those projects are under strain. Under the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty, only five nations — China, France, Russia, the U.K. and U.S. — can possess nuclear arms, and all have promised to reduce their stockpiles eventually to zero. But Israel, India and Pakistan all developed the bomb after the treaty emerged. More recently, the goal of curbing atomic arms has been challenged by North Korea’s entry into the nuclear club, by the U.S. withdrawal from an international deal curbing Iran’s nuclear program, and by threats by the leaders of the U.S. and Russia to augment their arsenals rather than continue to pare them down.

The Situation

Russia and the U.S. both suspended a landmark nuclear-weapons treaty in February, raising fears its end could restart the arms race in Europe and spur one in Asia. Each country accused the other of violating the 1987 pact, which rolled back ground-launched intermediate-range missiles deployed in Europe. If talks don’t revive the deal by Aug. 2, it would free both parties to deploy mid-range nuclear weapons not just in Europe but elsewhere, enabling the U.S. to counter deployment of such arms by China. President Donald Trump has said that in general the U.S. “must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability,” while his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin has boasted of his country’s work on next-generation nuclear-weapons systems. The U.S. has already withdrawn from a 2015 accord setting limits on Iran’s nuclear program, though Iran’s government has said it would continue to abide by the pact. Before the deal, Iran possessed enough enriched uranium for multiple bombs. A meeting between North Korea leader Kim Jong Un in 2018 raised hopes that the reclusive dictator was open to giving up his nuclear weapons, though it’s not clear what his conditions are and many analysts are skeptical he’d relinquish the arms.

The Background

The U.S. was the first to develop nuclear weapons and is the only country to have used them. It dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, hastening an end to World War II but at the cost of an estimated 300,000 lives. Within two decades, the Soviet Union, the U.K., France and China had their own arsenals. In the Nonproliferation Treaty, those powers and the U.S. promised to share nuclear technology for civilian purposes – energy generation and medical applications – with countries that foreswore nuclear arms. Today, 191 countries are treaty members. The International Atomic Energy Agency monitors the arrangement and accounts for global inventories of nuclear material that could be diverted for bombs. The nuclear-armed countries outside of these agreements — India, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea — are subject to trade restrictions and in some cases, sanctions. The U.S., Soviet Union and then Russia, U.K. and France have all reduced their nuclear arsenals, decreasing the total number of warheads from a Cold War peak of 70,000 to about 15,000 today.

The Argument

Arms-control advocates worry that any growth in the arsenals of the U.S. or Russia will make it blatantly clear that nuclear-armed states have no intention of giving up their weapons, undermining non-proliferation efforts. Other analysts say those efforts are largely futile anyway. They note that creating the bomb isn’t the technological feat it once was; many nations now possess the fissile materials and cadre of engineers to pull it off. And the penalties used to dissuade countries from going nuclear have lost much of their potency because of inconsistent application. While Pakistan and North Korea remain stigmatized, India and Israel have won waivers of restrictions on trade and military sales. At the same time, nuclear weapons may be declining in appeal as more countries look to emerging technologies for defense. Systems using artificial intelligence, robotics and bioengineering are on the sharp edge of a new generation of weapons, which may eventually require their own non-proliferation rules.

The Reference Shelf

-

The Arms Control Association details nuclear weapons arsenals worldwide and analyses the U.S. Defense Department’s nuclear strategy.

-

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was founded by the people who made the first bomb to help prevent their invention from spreading.

-

The Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons seeks to halt proliferation by making nuclear weapons illegal.

- The International Atomic Energy Agency maintains inventories of nuclear stockpiles used for peaceful purposes and helps countries get access to technologies.

- The Nuclear Suppliers Group keeps lists of controlled nuclear materials and technologies that are subject to export restrictions.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Lisa Beyer at lbeyer3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.