Never Mind Yield Curves. What’s Negative Convexity?

Never Mind Yield Curves. What’s Negative Convexity?

(Bloomberg) -- Analysts and traders are blaming a highly technical, though increasingly familiar, culprit for dramatic plunges in U.S. Treasury interest rates. The terms they use -- “negative convexity” and “convexity hedging” -- aim to explain a phenomenon that’s been compared to a beast in the market. The result can be a market distortion that has people jumping to the wrong conclusion about the likelihood of a recession. What does it all mean, and why does it matter?

1. What’s convexity?

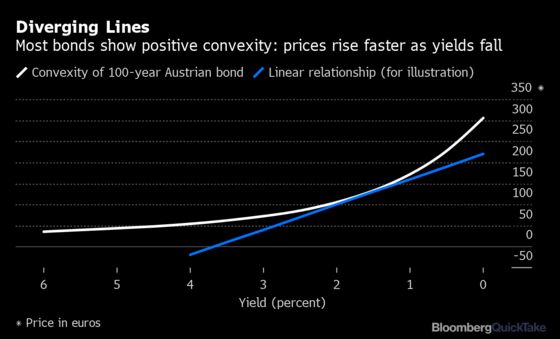

To take on convexity, we need to first grasp what’s known as duration. As interest rates drop, bond prices will rise and vice versa. The extent of the move is typically larger for bonds with a longer time to maturity. That relationship is known as duration. The change in the price and interest rate, or yield, of a bond isn’t linear. If you chart it with prices on one axis and interest rates on the other, you end up with a line showing the curvature in the relationship -- convexity. The higher the convexity, the quicker prices will rise as interest rates fall, and the opposite is true.

2. What’s negative convexity?

Most fixed-income bonds or securities have a positive convexity, which roughly means the price moves in the opposite direction to interest rates. But mortgage-backed securities have negative convexity. Their price tends not to rise as quickly, and can even drop, when Treasury and other market rates go down. That’s because the people holding the underlying mortgages are more likely to prepay and refinance into a lower rate. When that happens, the duration of the securities is shortened.

3. What’s convexity hedging?

Mortgage bonds are often held by large investors such as money managers and banks. They tend to prefer stable returns and constant duration as a means to reduce risk in their portfolios. So when interest rates drop, and mortgage bond duration starts to shorten, the investors will scramble to compensate by adding duration to their holdings, in a phenomenon known as convexity hedging. A hedge is basically investing in something that tends to go up when the first thing goes down (or vice versa). To add duration, so as to extend payments into a longer period, investors could buy U.S. Treasuries, which would further push down yields in the market. Or they could use interest-rate swaps, which are a contract between two parties to exchange one stream of interest payments for another.

4. Anyone else involved?

Asset-liability managers, typically insurance companies and pension funds that have to manage cash flows over time to meet future liabilities. Their ability to do that is affected as interest rates fall, so they have to plug the gap. One popular strategy for these funds is to also enter the swap market, where they would collect fixed rates and pay floating ones. That enables them to boost income without spending a lot of cash, which they would need to do if they just buy Treasuries.

5. What’s the impact?

Convexity hedging can become so large at certain trigger points that it can actually drive the whole Treasury market, meaning moves in yields can become exacerbated as players rush to adjust their portfolios. That was said to be the case in March, when the yield on 10-year Treasuries fell below that offered on the three-month for the first time in over a decade. (This is known as an inverted yield curve, the appearance of which often precedes a recession.) The inversion was fueled by this hedging activity, which pushed swap rates down further and faster than 10-year Treasury yields.

6. Can convexity hedging go in reverse?

Absolutely. A sharp rise in interest rates means fewer homeowners will refinance their mortgages, increasing the average repayment period and in turn extending the duration of the bond. In that scenario, big investors will try to reduce the duration in their portfolios -- perhaps by selling U.S. Treasury bonds or by entering into swap contracts where they pay fixed rates and receive floating ones. Again, this hedging can exacerbate the upwards moves in Treasury yields. Major “convexity events” in this direction occurred in 2003 and the so-called bond market massacre of 1994.

7. Are we done yet?

Yields on benchmark Treasuries are hovering around the lowest since 2016, suggesting there could be additional hedging to come. Analysts at Barclays, HSBC and Morgan Stanley, among others, have slashed their year-end forecasts for rates. JPMorgan said in mid-August that the longer mortgage rates “remain at depressed levels the more likely banks are to look to add duration.” However, chances of another severe convexity event might be lower since the U.S. Federal Reserve now holds much of the risk. The Fed, which bought a lot of mortgage-backed securities as part of its “quantitative easing” during the global financial crisis, doesn’t do much hedging.

8. So why does convexity matter?

If you care about the U.S. economy then you should care about convexity (really!). Many investors have been pointing to an inverted yield curve as a sign that recession could be looming. But if yields are being distorted by hedging activity, then there’s an argument that the signal sent by inversion is not as meaningful as it might otherwise be. If you combine convexity hedging with the idea that the premiums you get for locking your money up in Treasuries longer have been distorted by foreign inflows (as European and Japanese investors seek out better yields in American assets), then it’s possible the predictive power of an inverted yield curve really is different this time.

The Reference Shelf

- The New York Fed blogs on “Convexity Event Risks in a Rising Interest Rate Environment.”

- Here’s how Matthew C. Klein, who wrote for Bloomberg View, explained convexity.

- The CFA Institute blog looks at convexity hedging.

- Harley Bassman, creator of the MOVE index, wrote an article on the convexity vortex.

- The Bank for International Settlements working papers on mortgage risk and the yield curve, and the hunt for duration.

- QuickTakes explaining yield curves and what central banks in China, Europe and Down Under are doing to stimulate their economies.

--With assistance from Grant Clark.

To contact the reporters on this story: Stephen Spratt in Hong Kong at sspratt3@bloomberg.net;Tracy Alloway in Hong Kong at talloway@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tan Hwee Ann at hatan@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.