Negative Interest Rates

Negative Interest Rates

(Bloomberg) -- For more than half a decade, a basic truism of finance has been turned upside down. Interest rates — which normally reward savers and charge borrowers — have been set below zero by central banks in a handful of big countries. That means savings are losing value and borrowers can be paid to take out a loan. Considered one of the boldest monetary experiments of the 21st century, negative interest rates were adopted in Europe and Japan after policy makers realized that they needed extreme measures because their economies were still struggling years after the 2008 financial crisis. When the pandemic lockdowns halted commerce for months in 2020, central bankers looked for ways to cushion the blow. That rekindled a furious debate about whether rates in the red do more harm than good.

The Situation

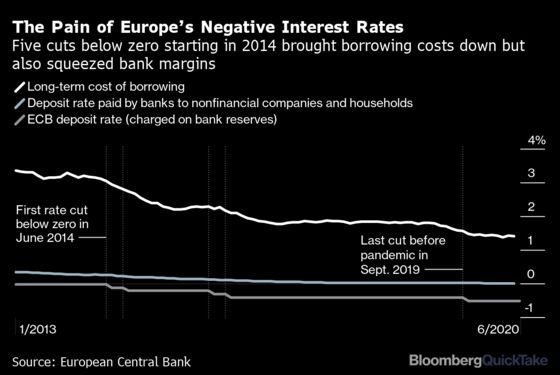

When the pandemic hit, the U.S. Federal Reserve quickly slashed its key interest rate back to near zero, where it had been for almost a decade after the financial crisis. President Donald Trump renewed his heckling of the Fed via Twitter, complaining that its reluctance to go negative put the U.S. at a disadvantage. Chair Jerome Powell repeatedly dismissed the idea, saying the Fed was worried that the policy could roil U.S. money markets and preferred to use other tools. What’s more, he said, research on the effectiveness of negative rates was “quite mixed.” Still, an undercurrent of worry led a market gauge reflecting traders’ expectations of future Fed policy to fall briefly below zero in May 2020, with some investors betting the Fed would have to take the plunge within a year. When the outbreak took hold, central banks that already had negative rates declined to lower them further, instead ramping up bond purchases and lending programs as the Fed has also done. The European Central Bank had cut its rate as recently as September 2019, charging banks 0.5% to hold their cash. But over the six years since ECB rates went negative, the policy has provoked increasing outcry that it has crippled banks and robbed savers. In Germany — a nation with a strong culture of socking money away — tabloid newspaper Bild railed against the central bank, casting former ECB President Mario Draghi as a savings-sucking vampire it dubbed “Count Draghila.”

The Background

The idea behind negative rates is simple: They drive borrowing costs lower and punish lenders that play it safe by hoarding cash. But economists argue about whether they also have perverse effects that outweigh the textbook economic benefits. Chief among them is the impact on bank profits. Since many banks are reluctant to start charging for deposits, the spread between the rate they pay for funds and what they can earn lending money can be squeezed. (Over time, European banks began to levy fees.) Critics fret that the slide in borrowing costs will eventually hit a “reversal rate,” where the policy backfires as banks become less willing to lend. To offset that possibility, the ECB introduced a series of targeted measures to lift bank profits, including a “tiering” system that exempted a portion of the money parked at the ECB from charges. There’s also spillover in financial markets: Because central banks provide a benchmark for all borrowing costs across an economy, negative rates spread to a range of fixed-income securities, with government bonds of countries such as Germany and the U.K. trading at negative yields. That means investors lose money if they hold the debt to maturity.

The Argument

Central banks that use negative rates say they’ve lowered borrowing costs and fueled more lending. ECB research has shown that the downside has been manageable. Even central bankers worried about the potential harm say the scale of the crisis triggered by the pandemic and the limited number of tools available to fight it mean they can’t rule anything out. Fans include Kenneth Rogoff, an economics professor at Harvard University, who argued in an article in May 2020 that objections are “either fuzzy-headed or easily addressed” and that only “effective deep negative interest rates can do the job” of reviving economies. Yet there are worries that negative rates will prove politically toxic, tainting the public view of central banks and threatening their hard-won independence. To many critics, the policy had outlived its usefulness even before the pandemic and could now prove harder to escape. In 2019, Sweden, which began dipping below zero in 2009, became the first country to reverse course in a bid to ease the pain on lenders and investment funds. The Bank for International Settlements, a study group of central banks, warned in a 2019 briefing that there’s “something vaguely troubling when the unthinkable becomes routine.”

The Reference Shelf

-

A Bloomberg Markets interview with economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff from May 2020, who argue that this time really is different, and an article on Denmark’s experiment with negative rates.

-

Narayana Kocherlakota, the former president of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, makes the case for negative rates in the U.S. for Bloomberg Opinion.

-

Bloomberg articles on how global central bankers joined Powell’s pushback on negative rates. The chorus of bankers have criticized negative rates and some central bankers say they may be doing more harm than good.

-

A QuickTake explainer on the black hole of negative-yielding bonds and another on how “tiering” is meant to cut the pain of negative rates.

-

A Bloomberg comic explains how negative interest rates aim to put money to work.

-

The Bank for International Settlements published a March 2016 report on negative rates and a 2019 briefing.

-

Janet Yellen, the former U.S. Federal Reserve chair, said in 2015 that a change in circumstances could put negative rates “on the table” in the U.S.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.