Money to Launder? Here's How (Hint: Find a Bank)

Money to Launder? Here's How (Hint: Find a Bank): QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- You’re a criminal with millions of dollars in ill-gotten gains but one big problem: Transferring slugs of money or carrying suitcases of cash will raise eyebrows. You need to “launder” the dough — make the dirty money appear to be the proceeds of legitimate enterprise. Then it can be spent anywhere in the world — say, on real estate or luxury yachts — no questions asked. Most countries and all the world’s major banks have controls in place to flag suspicious funds coming into the financial system. But as shown by a series of revelations and the probes roiling European banks, bad actors come up with innovative ways to skirt the rules.

Hiding under shell companies

Deliberately opaque “shell” companies, which exist only on paper and have no active business operations, are easy and cheap to set up and effective at obscuring ownership. They’re key to what experts call the “layering phase” of money laundering, in which funds are shoveled around multiple times to make them harder to track. Shell companies are traditionally found in offshore tax havens such as Panama and the Bahamas, but the U.S. states of Delaware and Nevada also permit corporations to be set up in anonymity. The international consortium of journalists that uncovered the Troika Laundromat scheme says it involved at least 75 shell companies that generated a total of $8.8 billion in transactions through made-up deals. There’s been a global push for more transparency, even in the U.K., whose crown dependencies include Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man.

Finding weak links

After the chaotic collapse of Soviet Union, launderers searched out weak spots in Europe, where watchdogs were ill-equipped. They looked for banks that might be poorly supervised or even open to being complicit. Torrents of cash were channeled into banks in Cyprus and Malta. Baltic nations Estonia and Latvia, which have central roles in the emerging tale of dirty Russian money, became big players as passageways to the West. The former Soviet states had an added draw because Russian is widely spoken, and Scandinavian lenders rushed to get into the high-growth markets. By way of western correspondent banks, funds could be further cleansed and moved around with less scrutiny. Denmark’s Danske Bank A/S has acknowledged that much of about $230 billion that flowed through its tiny Estonian outpost may have been dirty.

Trade-based money laundering

Criminals can move funds across borders by engaging in seemingly legitimate international trading of goods and falsifying invoices to disguise their true value. Such trade-based laundering was key to the Troika Laundromat scheme, where bogus invoices were allegedly used to trade “food goods,” “metal goods” and “auto parts.” The method is widely used to enable outflows from developing economies. Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based research organization, estimates that “trade misinvoicing” accounts for 18 percent of developing nations’ trade with developed economies.

Mirror trades

A “mirror trade” is two stock transactions, in two separate locations, that effectively cancel each other out but succeed in moving money from one place to another. Mirror trades have legitimate uses, and are employed by mutual funds and other investors that have limits on where they can hold securities. But such trades can also be used to bring money across borders. In one infamous example, Deutsche Bank AG helped clients move about $10 billion out of Russia from 2011 to 2015 by executing mirror transactions in its offices in Moscow and London. The bank was fined $629 million by U.K. and U.S. authorities for those compliance failures. A criminal investigation by the U.S. Justice Department has yet to conclude. Another technique, sometimes known as a back-to-back deal, is to take a loan in one country that’s secured by a deposit in another country. The launderer defaults on the loan, the bank seizes the deposit and the money looks clean. The fact that both types of transactions have legitimate applications makes them harder to stop.

Mixing clean and dirty money

It’s difficult to tell the difference between legitimate business and illicit flows from criminal activity. Launderers sometimes work with real companies that generate lots of cash, merging their funds before they head to the bank. Casinos and other cash-based operations such as restaurants are attractive targets. A common scheme involving casinos is to buy large amounts of chips in cash, gamble just a tiny share, then call the rest winnings and redeem the funds. Even more effective is owning the whole casino. Macau, the world’s biggest gambling hub, has long been beset by money laundering despite repeated attempts by China’s government to rein it in. Canada found last year that casinos in British Columbia for years served unwittingly as laundromats for domestic and international crime. The expansion of online gaming and sports betting, where identities are easy to conceal, provide new opportunities, as do cryptocurrencies.

‘Smurfing’

To avoid raising red flags, money launderers will break down a large amount of money into smaller chunks and have associates known as “smurfs” deposit the funds in different accounts in different places. U.S. banks are required to report to regulatory authorities any transaction of more than $10,000, so launderers often avoid hitting that limit. Banks must continuously track customer transactions to look for red flags, and if they have good reason to suspect something devious, they must alert authorities. Failure to do so can bring stiff fines. Banks often complain that the rules are onerous and the controls needed to “know your customer” are costly. Danske Bank increased the number of employees in compliance after its money-laundering scandal exploded, and now has more than 1,000 people assigned to monitor and prevent financial crime.

The Reference Shelf

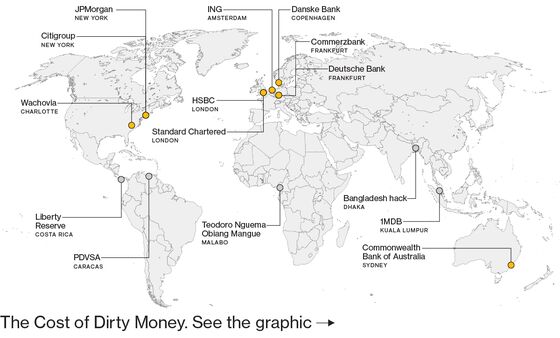

- Bloomberg’s interactive map of notable enforcement efforts around the world.

- A report from Bloomberg Intelligence on the cost of compliance.

- What we know and don’t know about the Troika Laundromat.

- The website of Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based non-profit that analyzes dirty money flows.

- A U.S. Congressional Research Service report on efforts to counter money laundering.

- QuickTakes on how Europe’s banks ended up laundering Russia’s money, on Latvia’s financial corruption and on Deutsche Bank’s mirror trades.

- A column by Bloomberg Opinion’s Leonid Bershidsky on the perils of trade-based money laundering.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.