Minimum Wage

Minimum Wage

(Bloomberg) -- There’s no such thing as a free lunch. Or is there? For more than a century, politicians have been passing minimum wage laws and opponents have warned of their hidden costs. The argument is simmering anew in Washington: Does a minimum wage lead to better lives or fewer jobs, more prosperity or less? And even if a minimum wage is the right public policy, is a one-size-fits-all, nationwide hourly dollar figure the best approach?

The Situation

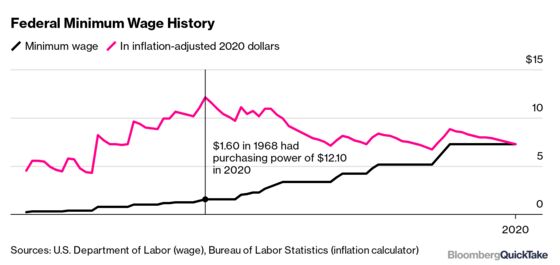

The U.S. minimum wage, $7.25 an hour, hasn’t been raised since 2009. But 29 states and at least 52 cities and counties have lifted their pay floors above the national mandate. So have a number of corporations including Walmart Inc., which now offers minimum starting pay of $11 an hour, and Amazon.com Inc., which raised its minimum wage in the U.S. and the U.K. to $15 an hour. The Democratic Party, in Congress and through its candidates seeking to challenge President Donald Trump in the 2020 election, wants to more than double the nationwide minimum wage, to $15 an hour, over the course of several years, and automatically increase it to keep pace with inflation. Trump said in mid-2019 that he was considering backing a $15 minimum wage, which would have put him at odds with much of his Republican Party. But then the White House Office of Management and Budget came out in opposition to the proposal, saying Trump’s economic policies were “increasing workers’ take-home pay far more effectively and efficiently.” Meantime, the $7.25 rate, unchanged for more than a decade, becomes less meaningful each year due to inflation. Among 32 countries that report minimum-wage data to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. rate ranked 14th in purchasing power parity in 2018. (Luxembourg was at the top, followed by Australia.) More telling: When minimum wages are measured as a share of average wages, the U.S. ranked at the bottom of the list at 23%, behind Mexico, Spain and Greece.

The Background

New Zealand established the first minimum wage in 1894. In 1938, the U.S. Congress passed a law setting the national minimum wage at 25 cents an hour. It took until 2014 for high-wage Germany to adopt its first minimum wage, then about $9. That same year, Swiss voters rejected a proposal to establish the world’s highest — $25 an hour. Even after decades of research, economists are divided on how government-set minimum wages influence employment, incomes and societal well-being. Through the 1990s, many studies concluded that higher wage floors, while helping those who earn the minimum, also lead to fewer jobs. A landmark 1993 report compared employment at fast-food outlets in New Jersey and Pennsylvania one year after New Jersey raised its hourly minimum wage from the federal rate of $4.25 to $5.05. Relative to stores in Pennsylvania, which kept the lower federal rate, fast food restaurants in New Jersey increased employment by 13%. “Our empirical findings challenge the prediction that a rise in the minimum reduces employment,” the authors wrote. But an analysis released by the Congressional Budget Office in July 2019 found that while adopting a $15 minimum wage by 2025 would lift 1.3 million people out of poverty and deliver a raise for millions more, it would also cost 1.3 million other Americans their jobs.

The Argument

The benefits of raising the minimum wage are obvious, the potential pitfalls less so. Proponents note that full-time minimum-wage workers wouldn’t rely as much on public assistance programs such as food stamps to make ends meet and would use their bigger paychecks to buy more stuff, which would boost the economy. They also point to studies showing that raising the minimum wage reduces employee turnover. Opponents say the minimum wage, though promoted as helping low-skilled workers and the working poor, actually benefits lots of young people and workers from non-poor families. There’s an argument to be made that local and regional minimum wages are more appropriate than a nationwide one, given disparities in economic conditions, the job market and cost of living in different parts of the U.S. Anyway, with so many states and cities taking it upon themselves to require higher minimum pay, the importance of the federal minimum wage is declining. In 2018, just 2.1% of the country’s 81.9 million hourly workers earned $7.25 or less. That was the lowest proportion of the hourly workforce since measurements started in 1979, when the number was 13.4%.

The Reference Shelf

- The U.S. Department of Labor explains how the minimum wage came to be in 1938, and economists David Neumark and William Wascher explore its history and evidence for and against it.

- How inflation eats away at any minimum wage that’s not automatically adjusted each year.

- The UC Berkeley Labor Center’s inventory of city and county minimum wages.

- The Center for Economic Policy and Research’s argument for raising the wage and the Cato Institute’s arguments against.

- The National Review on the specific objection to a national minimum wage.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics report on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of low-wage American workers.

- OECD data on member nations’ minimum wages.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Laurence Arnold at larnold4@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.