Middle East Takes Small, Uneven Steps on Women’s Rights

Mideast Takes Small, Uneven Steps on Women's Rights: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- The news made headlines around the world: Saudi Arabia, the only country to bar women from driving, ended the ban in June 2018. Pioneers hit the roads to cheers — and stares — and celebrated the demise of a notorious restriction on the freedom of women. But the advancement of women’s rights is uneven at best in Saudi Arabia, as well as across North Africa and the Middle East, a region that regularly rates worst or second worst to sub-Saharan Africa in overall assessments of gender equality. The role of women is the subject of sustained public debate, with campaigns for equal treatment resisted by entrenched patriarchal and conservative forces.

1. Why did Saudi Arabia let women start driving?

The change came amid the Saudi monarchy’s ambitious campaign to diversify the economy and wean the kingdom from dependence on oil revenue. If more women are to have paying jobs, they need to be able to drive to work. Promoting civil liberties wasn’t really the point. In fact, the government jailed some of the country’s most prominent women’s rights campaigners before the driving ban was lifted, accusing them of collaborating with unspecified hostile foreign entities.

2. How big a step was this for the Saudis?

It was significant, both symbolically and in the freedom it gives women to engage more fully in society. But it was a small step toward equality. The main roadblock is guardian-consent requirements, which make women legal dependents of male relatives — fathers, husbands, brothers, uncles or sons. A woman can’t marry, obtain a passport or travel without the permission of her designated guardian. Small changes made recently suggest the government could be dismantling these rules gradually.

3. Where is progress being made?

Advancements are most pronounced in Tunisia, birthplace of the pro-democracy uprisings known as the Arab Spring that started in late 2010. The country’s 2014 constitution, heralded by activists as a model, affirms equal rights and duties for male and female citizens and says the state will strive to achieve parity in all elected assemblies. Tunisia stands out as well for overturning legislation banning Muslim women from marrying non-Muslim men — a prohibition still common in the region — and for a proposed measure that would equalize inheritance rights of sons and daughters. That’s a particularly controversial undertaking in a region where laws typically award daughters half of what sons receive, in line with conventional interpretations of Islam’s holy texts. Tunisia has also enacted laws against economic discrimination and harassment of women.

4. What advances have women made elsewhere?

Since the Arab Spring, domestic violence has been a target of legal reform, with seven of the 20 Muslim-majority countries and territories in the region joining Tunisia in criminalizing it. They include Morocco, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. Six governments have repealed colonial-era laws that allowed rapists to escape prosecution by marrying their victims to preserve family “honor.” And women are breaking into traditionally male spheres. The United Arab Emirates’s first female fighter pilot led the country’s initial airstrike against Islamic State in Syria in 2014. A Jordanian woman became the first from a Middle Eastern country to become a professional wrestler. One in three startups in the Arab World is founded or led by women.

5. Are women gaining political power?

Slowly. Women’s representation in national parliaments rose to an average of about 17.5 percent in 2017 from 4.3 percent in 1995; the global average is 23.4 percent. Mostly since 2010, 11 nations and the Palestinian Authority have adopted legislation to increase women’s participation in politics, mainly through quotas that ensure a minimum percentage as candidates for office — with Tunisia one of the few countries in the world to require equal gender representation across candidate lists. In 2011, Saudi Arabia became the last country to extend the vote to women. The U.A.E. elected the region’s first female parliamentary speaker in 2015, and a handful of women have won mayoral elections, including in Baghdad, Tunis and Bethlehem, in the West Bank. Tunisia recently appointed a woman as deputy head of the Central Bank.

6. What are the biggest hurdles that remain?

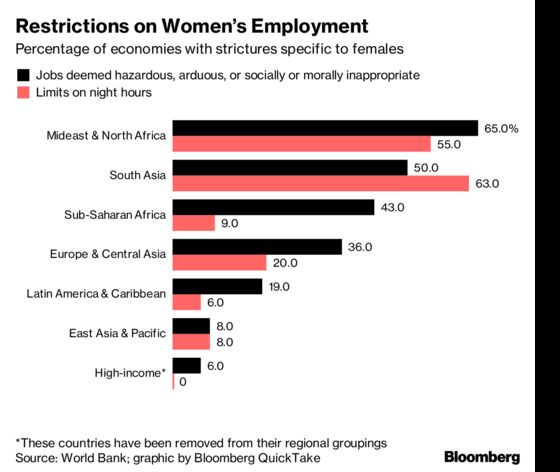

Twelve of the 15 countries in the world with the lowest rate of female participation in the workforce are in North Africa and the Middle East, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2017 Gender Gap report. Societal pressure remains strong, especially outside urban areas, for women to stay home. Among other obstacles to equality are laws giving a husband the right to unilaterally divorce his wife, plus disregard for, and weak enforcement of, rules against child marriages. And women continue to pay for speaking up. In Iran, dozens were arrested in early 2018 in connection with protests against the requirement that women wear veils in public. Not long after, one was detained in Egypt and held for three months for complaining, in an online video, about sexual harassment.

The Reference Shelf

- A survey of feminist activism in North Africa by Professor Valentine Moghadam.

- An obituary of Fatima Mernissi, a Moroccan sociologist and women’s rights campaigner who died in 2015.

- A World Bank Report on the status of women in the Arab World.

- Fifty Million Rising, a book by economist Saadia Zahidi, who argues that the greater numbers of women joining the workforce will reshape how women are viewed in the Muslim world and beyond.

To contact the reporter on this story: Caroline Alexander in London at calexander1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Lisa Beyer, Anne Reifenberg

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.