Why Supply Chains Are Entering Third Year of Chaos: QuickTake

How Supply Chains Broke, Sparking Global Shortages

(Bloomberg) --

For two years, the pandemic threw the vital but usually invisible world of logistics into a tailspin, creating shortages of goods including masks, memory chips, plastic polymers, paper towels and bicycles. Though the cargo industry’s ships, trains, trucks and planes continued to run full steam, they struggled to absorb the rolling tremors from Covid-19 — jolts to consumer demand, idled factories, employees getting sick or forced to work from home. The result: a sudden shortage of shipping containers, long delivery delays, a sustained period of soaring freight rates and higher prices for consumers. Now, Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s continued hard line against Covid outbreaks pose the latest difficulties; both increase the uncertainty and costs of operating still-hobbled supply chains smoothly.

1. Why do containers matter?

Because there’s a limited supply of them to meet what’s become unpredictable demand. There are about 25 million standardized shipping containers plying the seas on about 6,000 ships in a fragile network designed to stay synchronized with ports, railroad junctions, trucking depots and warehouses. They’re the backbone of globalization, an interconnected system that has lifted millions of people out of poverty and created a generation of discount-minded shoppers. In normal times, globalized supply chains worked so well they led to the widespread adoption of more efficient just-in-time inventory management. However, the Covid crisis led to unusual swings in the demand for goods as well as on-again, off-again lockdowns. The disruptions left handlers of containers struggling to manage traffic, causing shortages of the 20- and 40-foot boxes where and when they were needed most. Companies’ fears of running out of parts or merchandise exacerbated the problems by encouraging many to over-order to pad their stockpiles. In 2022, just-in-case inventory management has become the trend in a world facing many of the previous risks along with fresh geopolitical worries.

2. Why is China’s Covid strategy important?

Home to six of the 10 largest container ports, China is still the global economy’s most important manufacturing hub and an export powerhouse. While most countries have decided to learn to live with the coronavirus, Beijing has maintained a so-called Covid Zero policy where even small outbreaks can shut down large population centers and slow economic activity. In Shenzhen, companies including Apple Inc. supplier Hon Hai Precision Industry, better known as Foxconn, had to temporarily shut for a week in March. In Changchun, an industrial hub that accounted for about 11% of China’s total annual car output in 2020, automakers such as Toyota Motor Corp. were forced to close. If such crackdowns continue to be so strict, there’s likely to be both a dampening effect on China’s domestic growth as well as wider disruptive effects to global trade — 80% of which moves on ships.

3. Why do Russia and Ukraine matter?

Mostly because they’re key players in the production of oil and natural gas. Energy prices have soared since Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, increasing costs for truckers and raising the risks of strikes. Food supplies are under threat because the countries fighting each other are big producers of wheat and fertilizer. They’re also important exporters of industrial raw materials such as nickel, lumber and neon gas. That last item might sound easy to do without, but it’s actually vital for making semiconductors; according to one estimate, Ukraine produces 50% of the world’s purified neon. Russia accounts for 5% of overall seaborne trade, but its links to the global economy aren’t insignificant. More than 2,100 U.S. companies and 1,200 in Europe have at least one direct supplier in Russia, and the total reaches 300,000 when indirect suppliers are included, according to Arlington, Virginia-based Interos, a supply-chain risk management company. With sanctions blocking most commerce with Russia, many companies are scrambling to find suppliers elsewhere as well as shipping routes that avoid the conflict zone altogether.

4. Where are shipping rates headed?

At the peak of the supply strains in October 2021, spot rates charged by ocean carriers had surged ten-fold from a year earlier, but those have been edging down since then. The cost for a 40-foot shipping container on the benchmark transpacific route fell about 11% in the first quarter of 2022, according to Drewry, a shipping industry consulting company. That’s a typical move after the Christmas and Chinese Lunar New Year holidays, and rates are still more than double what they were a year earlier. It’s an open question whether the recent drop marks the beginning of a longer-term slide back to pre-pandemic levels driven by weaker import demand or a seasonal adjustment that’ll correct when inventory-building picks up again. Either way, ocean freight rates that are still several times higher than 2019 levels are feeding inflation. According to research by the International Monetary Fund, “when freight rates double, inflation picks up by about 0.7 percentage point. Most importantly, the effects are quite persistent, peaking after a year and lasting up to 18 months. This implies that the increase in shipping costs observed in 2021 could increase inflation by about 1.5 percentage points in 2022.”

5. How has the shipping industry fared?

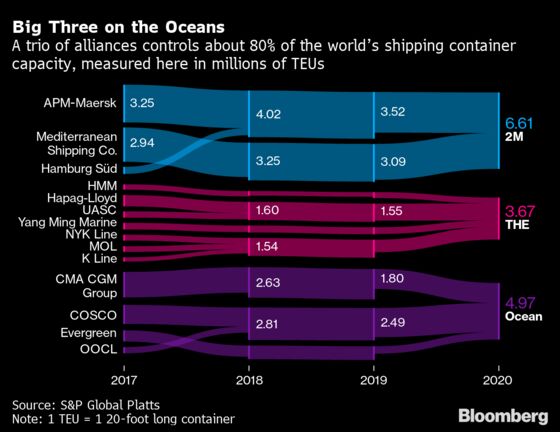

Some carriers — a mix of publicly traded, privately held and government-backed firms mostly based in Asia and Europe — have enjoyed some of their highest-ever profits. Some politicians blame concentration in the shipping industry for dulling price competition. In 2017, about a dozen container lines that control 80% of the global market formed three main alliances to share ships, cooperate on routes and limit excess capacity, an arrangement that has been likened to an oligopoly. Some busy trade lanes might have several competitors; smaller gateways for goods might have just one or two.

6. What can governments do?

U.S. and European regulators have raised questions about constrained competition. President Joe Biden, in a July 2021 executive order aimed at a number of industries, asked the U.S. Federal Maritime Commission to “ensure vigorous enforcement against shippers charging American exporters exorbitant charges.” The agency was already probing the practice of carriers returning containers to Asia empty rather than waiting for them to be filled with American exports because the eastbound route was so profitable. National authorities can influence a narrow range of industry practices. The Port of Los Angeles — which together with the nearby Long Beach port make up the busiest U.S. container hub — announced that it is moving to begin 24-hour, seven-day-a-week operation after discussions with the Biden administration and labor unions. Politicians like U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts are calling out the container carriers for contributing to inflation. However, the global nature of the industry means it’s mostly beyond the reach of national regulators, who are unlikely to be able to do much to control prices.

The Reference Shelf

- An Odd Lots Podcast: “Why the Cost of Shipping Goods From China Is Soaring.”

- Smithsonian Magazine article on McLean’s legacy creating the now-ubiquitous shipping container.

- A Jan. 20 report from Lee Klaskow, senior logistics analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

- The humanitarian crisis of stranded seafarers is explored in this Bloomberg.com story thread.

- Books on the impact of containerization include “Giants Of The Sea: Ships & Men Who Changed The World” by John McCown, and “The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger” by Marc Levinson.

- Bloomberg articles on nimble fleets, shipping bottlenecks, Ikea’s supply-chain outlook and the headwinds the crunch creates for the global economy.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.