How Race to 5G in U.S. Hit Speed Bump Called C-Band

How Race to 5G in U.S. Hit Speed Bump Called C-Band

(Bloomberg) -- From ovens to refrigerators, automobiles to surgeon’s tools, more and more items are connected wirelessly to the internet. As use of such devices soars, so does the demand for airwaves to carry all that data. The need for more space -- more spectrum -- to carry mobile signals is causing friction in a once-placid policy arena. One fight that erupted in the closing days of 2021 pitted mobile phones against the U.S. aviation sector.

1. What are airwaves, exactly?

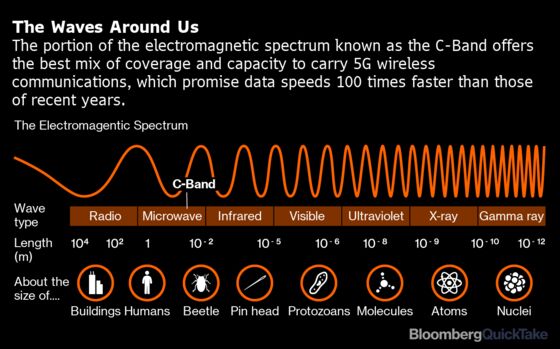

The term refers to the invisible electromagnetic waves that carry information through the atmosphere to our smartphones -- and to TVs, radios, iPads, ships at sea, aircraft, garage-door openers and any other gadgets that send or take in signals wirelessly. The so-called electromagnetic spectrum encompasses the full range of airwaves, from tiny, high-frequency waves like those used in radiation therapy to longer, low-frequency waves such as those that deliver radio programming. High-frequency waves can carry a lot of information but don’t go far and can be stopped by walls or even rain. Low-frequency waves go far and penetrate obstacles but don’t carry a lot of information. Of particular value in this wireless age are mid-band airwaves that can carry ample data for significant distances. One of those is the C-band.

2. What’s the fight over C-band?

This part of the spectrum offers an ideal mix of coverage and capacity to carry the emerging 5G wireless technology that promises data speeds 100 times faster than those of recent years. The C-band had been used by satellite providers to beam programs down to TV and radio stations around the country. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission wanted to open some of the C-band to 5G uses, a shift that dramatically increased demand for those frequencies.

3. Who owns the airwaves?

That’s a tricky question. By law, U.S. airwaves belong to the public; the federal government grants rights, expressed as licenses, to companies to use certain frequencies. These rights are rarely revoked, and when companies with licenses are sold, the airwaves rights typically transfer -- commanding a hefty premium from the buyer. In recent years, the FCC has arranged payment for TV broadcasters to leave frequencies that are needed for mobile uses. A swath of C-band airwaves was auctioned off in early 2021.

4. Who used to hold the C-band licenses?

Four satellite companies dominated activity in the C-band in the U.S. The two biggest were Intelsat SA and SES SA, both based in Luxembourg, which between them controlled about 90% of commercial traffic. Along with Telesat Canada of Ottawa, which also owned some C-band rights in the U.S., these companies made up the C-Band Alliance (CBA), which was formed in 2018 to push their ideas on how best to sell rights to their portion of the spectrum.

5. How did mobile phones get pitted against air traffic control?

The fight that burst into public view in the final days of 2021 was over whether a new service for mobile phones would interfere with the electronics airline pilots need to land their planes. Frequencies within the C-band are near airwaves used by aircraft radar altimeters -- sensitive devices that track altitude, allowing landings in foul weather and that also feed multiple critical safety systems. Some of the nation’s most powerful corporations and industries found themselves at odds. AT&T Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc. in January agreed to temporarily delay switching on hundreds of 5G cell towers near U.S. airports in last-minute talks with U.S. officials.

6. How are other countries handling this issue?

Some moved faster to free mid-band airwaves for use by mobile communications. South Korea, the U.K., Spain, Italy, Austria and China all held auctions or allocated the frequencies before the U.S. That put the U.S. behind in some aspects of what the wireless industry calls “The Race to 5G.” The term refers to efforts to establish a 5G network before other countries do, in order to foster the same type of tech leadership that helped boost world-leading brands such as Qualcomm Inc., Intel Corp. and Silicon Valley companies such as Google and Facebook Inc.

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake explainer of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- How Congress tried without success to settle how the proceeds are divided up.

- The FCC explains its auction process.

- Intelsat and SES were allies until they started feuding.

- Bloomberg Opinion columnist Alex Webb on Intelsat’s “debt tantrum.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.