How Musk’s Hyperloop Became Just a Loop in Chicago: QuickTake

Musk appears to have scaled down those ambitions somewhat, at least for an early version of the idea.

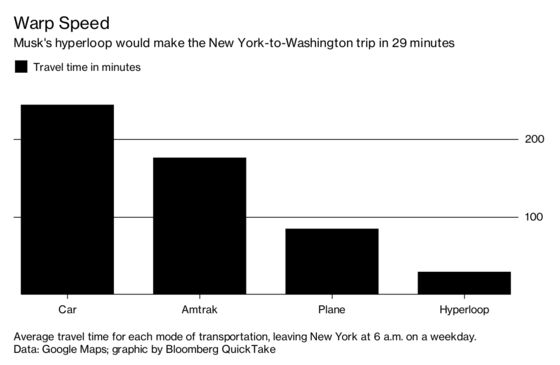

(Bloomberg) -- The numbers are pretty unbelievable -- at a top speed of 760 miles per hour (more than 1,200 kilometers per hour), the so-called hyperloop proposed by entrepreneur Elon Musk could whisk travelers from New York to Washington in 29 minutes, one-fifth the time needed by Acela, Amtrak’s fastest train. Now, Musk appears to have scaled down those ambitions somewhat, at least for an early version of the idea. He has won a bid in Chicago to build a high-speed express train to its O’Hare International Airport. It’s not quite a signed contract yet, but if the parties proceed, it will give Musk a chance to prove parts of his untested technology.

1. What’s the Chicago project?

The transit system aims to connect downtown Chicago with O’Hare, about 15 miles and a $40 taxi ride away. It will use "autonomous electric skates," analogous to train carriages, to carry eight to 16 passengers apiece. The pods will be made by Musk’s other company, Tesla Inc., he said. Boring Co. leaves room for the possibility of cars using the system, too. The website says a skate could also hold “a single passenger vehicle.” The system will run underground, giving Musk’s venture a chance to show off its tunnel-boring technology. The company has said it’s faster and cheaper than other subterranean projects. “Tunnel construction and operation will be silent, invisible and imperceptible at the surface,” the company said.

2. What’s a hyperloop?

Back in 2013, Musk published a white paper for a transportation system using a train-like capsule that -- to reduce movement-slowing friction -- floats on air and travels through a low-pressure tube. Much of the idea, as Musk acknowledged, came from predecessors including American physicist Robert Goddard, the "father of modern rocket propulsion." Some of the world’s fastest trains already float above their track, using magnetic levitation, or maglev. The world’s fastest operating train, the Shanghai Maglev, reaches top speeds well north of 200 miles per hour, and others are planned that will top 300. But that’s not fast enough for Musk.

3. How is Musk’s hyperloop different?

Rather than rely on maglev, which can be expensive to build, Musk in his white paper proposed using air bearings -- little versions of the jets that let hovercraft skim across water -- to lift passenger "pods." Linear electric motors would propel the pods through tunnels that have very little air in them. What air there is in front of each pod would be sucked in by a battery-powered electric compressor and released in the rear, supplying the air bearings along the way. The project in Chicago appears to use pods, which Boring Co. is calling skates, but not a vacuum. The company has dubbed it Loop rather than hyperloop.

4. Is this fantasy or really possible?

While engineers say a hyperloop is technically possible, it’s expensive and would require complicated permitting and approvals in the U.S. and in many other countries. "The obstacles facing a run-of-the-mill highway, tunnel or bridge are great enough," Bloomberg View columnist Virginia Postrel wrote. "Throw in untried and unfamiliar technology and you’re asking for endless delays." Writing in Wired, Ricki Harris dismissed the hyperloop as "just the latest too-good-to-be-true pledge from the tech world," on par with the promise that we’d all be using Segways by now.

5. Is Musk alone in this?

Not anymore. When he wrote his white paper in 2013, he said he was too busy with his other companies, automaker Tesla Inc. and rocket developer Space Exploration Technologies Corp., to execute his idea, and he encouraged others to delve into it. They did. (Musk does have a trump card -- the trademark for “Hyperloop,” which he holds through SpaceX.)

6. Who are the other players?

The Los Angeles area is emerging as a hyperloop center, home to competitors Arrivo, Hyperloop One, and Hyperloop Transportation Technologies. Boring Co. also has its base there. A team from the Technical University of Delft in the Netherlands that won a SpaceX-sponsored contest for transportation technology has started Hardt Global Mobility, which is working on a hyperloop test facility in Europe.

7. What else has Musk proposed?

In July 2017, Musk tweeted that he’d received "verbal government approval” for a hyperloop connecting New York and Washington, before backing off on the approval claim. That route would be attractive because it runs through a high-population region with no shortage of potential riders. But precisely because of its density, securing all the necessary permission will be difficult. Originally, Musk had proposed Los Angeles to San Francisco, but that route has myriad challenges, among them rights-of-way conflicts.

8. Why is existing train service in the U.S. so slow?

That’s as much a lament as a question. A proposal for a maglev train linking Las Vegas and Anaheim, California, ran out of steam a few years ago. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pitched then President Barack Obama on a maglev train that would link Washington and New York in one hour. Big challenges include fragmented private ownership of the land underlying proposed routes and vocal opposition in some areas. An effort is underway to build a Texas train with top speeds of 205 miles per hour connecting Dallas and Houston, but its future is uncertain. In California, voters in 2008 approved plans for a train connecting Southern California to San Francisco with top speeds of 220 miles per hour. Construction has begun, and the first segment is scheduled to begin operating in 2025.

The Reference Shelf

- A Tech Insider video on Musk’s revised plans for the Boring Company.

- Musk’s renewed interest might be bad news for his hyperloop rivals.

- MIT Technology Review checked out the technical and financial specs.

- A QuickTake explainer on Elon Musk.

- Keeping track of Musk’s ambitious goals.

- Why Musk’s hyperloop isn’t even his craziest idea.

- Popular Science took a look at the paperwork ahead.

To contact the reporter on this story: Sarah McBride in San Francisco at smcbride24@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Leah Harrison Singer at lharrison@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil, Laurence Arnold

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.