How Long-Feared ‘Monetary Finance’ Becomes Mainstream

How Long-Feared ‘Monetary Finance’ Becomes Mainstream

(Bloomberg) -- The coronavirus pandemic has turned into something of a break-the-glass moment for economic policy. One emergency measure involves governments borrowing from their own central banks to pay for extra spending. That idea, known as “monetary financing,” is getting hotly debated -- and perhaps even put into practice. To some, it’s just an extension of rescue plans that worked after the 2008 financial crisis. Others warn of a slippery slope that historically has led to out-of-control inflation.

1. What is ‘monetary financing’?

It’s when a country increases spending and at the same time creates the money needed to pay for it. That typically happens via central banks, which can either buy the bonds sold by a government to cover gaps in its budget -- or simply offer an overdraft, so that no bonds need to be issued in the first place. In either case, it’s often said that the effect is to “monetize the debt,” because policy makers have turned what would otherwise have been debt into money instead. The appeal in a pandemic is obvious, with governments everywhere spending record amounts of cash to bail out households and businesses, raising questions about whether private financial markets will be capable of absorbing an unprecedented deluge of sovereign debt.

2. How is this different from QE?

It involves more explicit cooperation between treasuries and central banks -- the latter might buy government debt directly, for example, instead of picking it up on secondary markets. In general, though, the dividing lines are blurry. In principle, the programs of quantitative easing or QE launched after the 2008 crisis were billed as ways to lower borrowing costs in the economy as a whole -- not just for governments heading deeper into debt. And the bonds bought by central banks were supposed to be sold back into private markets eventually -- not pile up on the public balance sheet. But in practice governments have been the main borrowers in the low-rates world of QE. And central banks now own so much of their debt -– especially in Japan, which launched the policy a decade before anyone else –- that few believe they can ever offload it all.

3. Who’s turning to monetary finance in the pandemic?

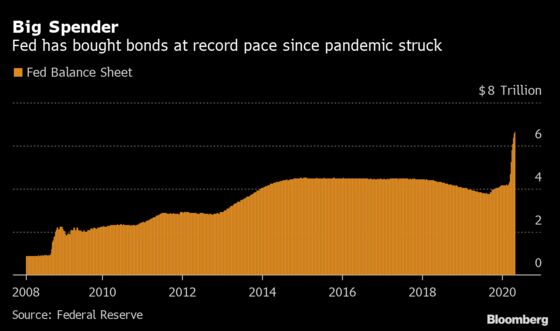

It’s hard to mark out where the Rubicon of monetary finance lies, and identify which countries have crossed it. But it’s easy to see movement in that direction. Central banks in the U.K. and New Zealand have extended overdrafts to their governments, while stressing that they’re temporary. Emerging markets are usually reluctant to get too unconventional for fear of scaring investors away, but monetary authorities in countries like Indonesia and Poland have started buying government debt. A debate is raging in India about whether policy makers should take a bolder step down that road. And the biggest developed economies have ramped up central-bank lending and government spending in parallel. That’s especially true in the U.S., where the Federal Reserve is buying Treasury debt on a scale that dwarfs 2008 and recalls the monetary-financing arrangements during World War II.

4. What’s the case for it?

The virus brought private business everywhere to a standstill. That’s changed the calculus for the officials in charge of public money, the only means available to plug a giant gap in demand and avert an even deeper depression. The argument is that it’s a once-in-a-lifetime emergency, and penny-pinching now represents a bigger risk: better to spend whatever it takes to keep businesses and households afloat, finance the relief effort by any means necessary, and worry about long-run consequences later. History and economics say that governments aren’t like households, and don’t have to repay debt the same way. Modern Monetary Theory, an emerging school of economics, argues that it doesn’t make much difference if public spending is financed by treasury bonds or central-bank reserves in any case -- both are government liabilities in the end. And the 2008 experience shows that governments and central banks can pump money into stalled economies without triggering inflation.

5. What’s the case against it?

It can’t work forever. The fear is that politicians handed this kind of money-creating power will eventually push it too far. Driven by election timetables or other short-term goals, they’ll splash too much of what feels like free cash around the economy. History is full of examples, from the Weimar Republic a century ago to Latin America today, of the disastrous effects of losing monetary discipline. To avoid such outcomes, modern developed economies keep elected politicians well away from the printing presses, handing the task to independent central banks instead. That’s why their money has credibility, the argument goes, and it was hard-won -- but it could easily be lost.

The Reference Shelf

- How the pandemic might actually trigger long-lost inflation.

- How monetary finance could be a back door to more burden-sharing for the EU.

- QuickTake Q&As explain the economic buzzwords: MMT, Japanification, central bank independence and the big rethink.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Noah Smith on how the pandemic has turned the world of economic policy upside down and Clive Crook on the implications for central bank independence.

- A 2015 IMF research paper by Adair Turner on the case for monetary finance.

- A 2019 Blackrock research paper on the need for unconventional central bank policies.

- Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank, argued in the Financial Times for a change of mindset.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.