How Late Payments to Vendors Spawned a New Business

How Late Payments to Vendors Spawned a New Business

(Bloomberg) -- It often makes good business sense to delay paying suppliers, keeping cash free for other purposes. Now the concept is being taken to new levels of complexity. A global industry has grown up of financial go-betweens who buy unpaid invoices at a discount. The firms give vendors cash sooner than if they’d waited for customers to pay -- if they’re willing to accept less than what they’re owed. Financiers say the practice, known as supply chain financing, is a “win-win” for all sides, but small business advisers call it “supply-chain bullying.” Regulators are wary, concerned that big companies use it to mask indebtedness and as a cover for crunching small contractors.

1. What is the point of supply chain finance?

In theory, it speeds up payments owed by businesses to their often cash-strapped suppliers. Third parties, traditionally banks and now also independent intermediaries backed by investors, pay suppliers the value of their outstanding invoices minus a discount. Proponents say the arrangement leaves all sides happy: Buyers get their goods weeks, or even months, before having to pay for them, while sellers get paid more quickly -- something many small companies aren’t used to. The intermediary closes the loop by collecting the full invoice amount from the buyer at a later date and profits from the spread.

2. Is this is a new idea?

Not entirely. It has historically been known as factoring or accounts receivable financing (they’re subtly different), and the third party was usually a bank such as Citigroup Inc. What’s relatively new are emerging financing platforms such as C2FO, PrimeRevenue Inc. and Greensill that partner with large companies to proactively arrange early payments to their suppliers. They have turned supply chain financing into a marketable investment product that pays returns of 5% or more. London-based Greensill, which packages buyer-confirmed receivables into bond-like instruments, in May attracted $800 million from SoftBank Group Corp.’s Vision Fund, a mammoth investor in tech startups around the world. The bet is that the market is crying out for a middleman to knit yield-starved institutional investors into the increasingly elaborate global supply chain.

3. How big is this business?

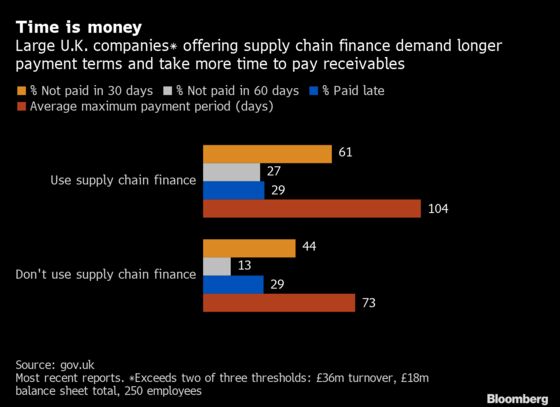

The size of the market is hard to pin down due to the lack of disclosure by companies that use it. Only about 6% of about 7,000 large U.K. companies currently disclose the use of early-payment programs for their suppliers, according to government data. Greensill estimates that global outstanding supply chain finance assets swelled to $100 billion this year. Consultancy McKinsey & Co. says that as much as $2 trillion in payables could be financed this way in the future.

4. What’s the downside?

Small business lobbyists compare supply chain financing to throwing a life jacket to someone you’ve just chucked overboard. There would be little need for it if companies adopted prompt payment practices. But for big corporations, delaying payment can boost cash flow and burnishes a key metric known as “working capital.” However, it doesn’t always end happily. Carillion, a collapsed British building contractor, has become the poster child of how a program meant to improve the financial security of small businesses fed the reckless management of a big one. In its final year of business, Carillion lengthened its standard payment terms to 120 days and encouraged suppliers to use its bank-financed Early Payment Scheme. The result was that Carillion rapidly built up 500 million pounds ($609 billion) of debt that wasn’t counted as such.

5. Why are watchdogs concerned?

Though it was entirely legal, Fitch Ratings Ltd. has characterized Carillion’s use of supply chain finance as “an accounting loophole” that may be more widespread than investors realize. The lack of uniform auditing rules means the issue is proving increasingly divisive. Companies from Australian builder Cimic Group Ltd. to French retailer Casino Guichard-Perrachon SA have faced -- and rebuffed -- criticism about their use of trade finance. The design of the programs can also be curiously complex. Until recently, telecommunications giant Vodafone Group Plc invested 1 billion euros ($1.1 billion) of its reserves into a fund managed by Greensill that contained thousands of its own unpaid bills. The investment existed on Vodafone’s balance sheet as an asset that offset its debts. The company discontinued the program seven weeks after its structure was first reported.

6. What might change?

The U.K. became the first country to require the disclosure of payment practices for all large public companies, which should reveal who are the worst offenders -- and could someday lead to penalties for deadbeats. Lawmakers say transparency is crucial to “making payment behavior a reputational, board room issue.” The U.K. government has publicly criticized firms with enormous supply chains such as Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc and BHP Group Plc. The country’s audit watchdog has urged its international counterparts to “explicitly and more comprehensively” define rules. In China, the Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission has issued guidelines for controlling risk in supply chain financing, forcing banks and insurers to guard against illegal profiteering. The unsettled question is whether supply chain financing creates more problems than it solves.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg News: SoftBank Makes $800 Million Bet on U.K Financier Greensill.

- Vodafone Invests in Fund Making Money Off Its Own Late Payments.

- Bloomberg Opinion: A $100 Billion Finance Industry Flies Under Radar.

--With assistance from Ali Ingersoll.

To contact the reporters on this story: Oliver Telling in London at otelling1@bloomberg.net;Thomas Beardsworth in London at tbeardsworth@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Vivianne Rodrigues at vrodrigues3@bloomberg.net, Andy Reinhardt, Melissa Pozsgay

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.