How Iran Pursues Its Interests Via Proxies and Partners

How Iran Pursues Its Interests Via Proxies and Partners

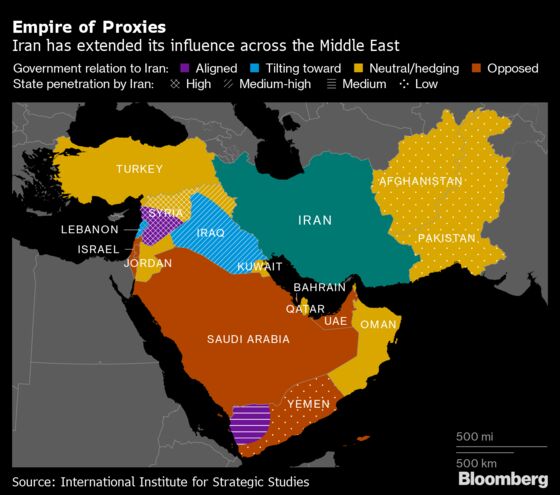

(Bloomberg) -- For more than 15 years, Western diplomatic tussles with Iran focused on its nuclear program and the ballistic missiles that could carry nuclear warheads it might one day produce. Yet by far the most powerful weapon that leaders in Tehran had at their disposal as they extended their influence across the Middle East was a network of foreign militias, built by Major General Qassem Soleimani, the iconic commander killed in Iraq by a U.S. drone strike Jan. 2. Soleimani’s proxy fighters -- from Afghanistan to Yemen -- are likely to remain Iran’s main weapon in an asymmetric fight against the vastly superior conventional weaponry and forces of the U.S. and its allies.

1. What’s the root of Iran’s network?

Iran has been funding and arming militant groups abroad since soon after the 1979 Islamic Revolution as the nation’s new fundamentalist Shiite Muslim leaders sought to spread their mission to the rest of the region. The limits of their ability to prevail in open conflict became apparent during the 1980-1988 war that quickly followed with Iraq, from which Soleimani’s Al Quds unit emerged from Iran’s premier military force, the Revolutionary Guard Corp. Though Iran fought Iraq’s better armed, Western-backed forces to a standstill, the economic and human cost was devastating. Iran’s leaders have avoided open warfare since, preferring the deniability and lower casualty rates offered by the use of covert operations and proxy forces.

2. Where did the network begin?

The initial focus of Iran’s militia strategy was in Lebanon, where it backed the Shiite Hezbollah group, formed in 1982 in reaction to Israel’s occupation of the country’s south. Soleimani’s Al Quds unit was designed, Khamenei said in 1990, to “establish popular Hezbollah cells all over the world.” That policy expanded dramatically after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, which brought about 150,000 American troops to Iran’s border, as well as a long-sought opportunity to dominate Iraq -- once part of the Persian Empire based in what is modern-day Iran -- through the country’s newly empowered Shiite majority. Under Soleimani’s direction, the Revolutionary Guards began organizing and arming Shiite militias with roadside bombs and other equipment to attack U.S. forces in Iraq, with the goal of driving them out.

3. What have these proxies done for Iran?

Iran’s backing of Shiite militias in Iraq has moved into the open since 2014, when the Iraqi government formally endorsed them as a means to fight Islamic State, under the umbrella designation of Popular Mobilization Forces. Their firepower and prominence have given Iran leverage to shape Iraqi governments. Soleimani himself moved from the shadows to appear in images posted on social media on the front lines with the units, as Iran claimed success for defeating Islamic State. In Syria, Iran intervened to preserve its only state ally, Bashir Al-Assad, against what began in 2011 as a popular rebellion, mainly among his country’s majority Sunni population. Unwilling to commit large numbers of its own troops, Iran enlisted Hezbollah and militias from Iraq, as well as Shiites from Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight in Syria. Though it took Russia’s help, the policy succeeded in saving Assad and securing a land route for Iranian military supplies, from Tehran to Lebanon. In Yemen, meanwhile, Iran backed Shiite Houthi rebels against forces supported by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in a war that broke out in 2015. According to a detailed study of Iranian-backed proxies by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Iran’s influence in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen is now “a new normal,” a concept once unthinkable even for leaders in Tehran.

4. To what extent does Iran control its allies?

It varies. The IISS study categorizes Iran-backed militias according to degrees of closeness. On one end is a group such as Iraq’s Kataeb Hezbollah, whose hostilities with the U.S. preceded the U.S. strike on Soleimani. Kataeb Hezbollah is in effect a state organ that would cease to exist without Iranian direction. In the middle is an ideological ally such as Hezbollah, which would pursue common goals even if Iran lost interest. At the other end is the armed Palestinian group Hamas, a partner of expediency that will align with Iran only so long as that serves its financial and political interests. All are happy to take Iranian cash and arms, but their loyalty, resources and commitment vary.

5. What does the network cost Iran?

Nathan Sales, the U.S. State Department’s top counter-terrorism official, said in 2018 that Iran funds Hezbollah to the tune of $700 million annually and gives a further $100 million to Palestinian organizations the U.S. designates as terrorist, including Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, both of which are Sunni. There is no way to independently verify those figures or Sale’s statement that Iran spends “billions” of dollars each year on its entire portfolio of foreign proxies. Given that academic estimates for Iran’s spending on the war in Syria alone range from $30 billion to more than $100 billion to date, the costs are significant, although relative to conventional warfare -- a U.S. Congressional Budget Office report estimated the cost to the U.S. of its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to 2017 at $2.4 trillion –- this is war on the cheap.

6. Have there been setbacks?

Yes. Soleimani had to go to Russia to ask for help in Syria, after his special forces and Shiite militias failed to turn the tide in Assad’s favor. More recently, Iran’s success in extending its influence has triggered local resentment and protests in Iraq and Lebanon against Iran and its clients.

7. What does all this mean for the U.S.?

Iran’s immediate response to the killing of Soleimani was a direct missile assault by its forces on U.S. military bases in Iraq; it produced no U.S. casualties but allowed Iran’s leaders to say openly that they’d hit back. The proxy infrastructure Soleimani set up before his death provides the means to strike back further at U.S. interests across a region that hosts tens of thousands of American troops, diplomats and companies. In the past, Iran calibrated its aggression against the U.S. carefully, hoping to avoid open, conventional warfare in which it would be outgunned. Many analysts believe Iran will continue such a calibrated approach.

The Reference Shelf

- Related QuickTakes on Iran’s nuclear program, its Revolutionary Guard, Syria’s war, Yemen’s war, Hezbollah, Hamas, and Qassem Soleimani.

- An International Institute for Strategic Studies report on Iran’s proxies

- Bloomberg News details the planning of the strike on Soleimani.

To contact the reporter on this story: Marc Champion in London at mchampion7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Lisa Beyer, Riad Hamade

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.