How Flu’s Mutations Threaten Birds, Pigs and Humans

How Flu’s Mutations Threaten Birds, Pigs and Humans

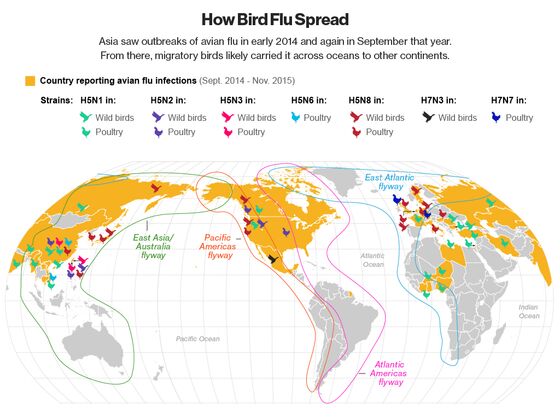

(Bloomberg) -- New strains of influenza are constantly emerging. Although the virus is associated with winter flu epidemics in people, wild migratory birds are its main target -- and are responsible for much of its global distribution. From them it may jump into mammals, especially pigs, where new strains can incubate. In general, novel flu viruses are a threat for birds, sometimes a problem for pigs, but are seldom a major issue for humans. Occasionally, though, new strains capable of infecting people do emerge, raising concern because of the potential for them to mutate and become better suited to person-to-person transmission, like the H1N1 swine flu that sparked a pandemic in 2009.

1. What’s the risk?

Horses, ferrets, dogs and even sea otters are susceptible to flu, but birds and pigs are the main worry for humans. The possibility of a pandemic arises when flu is passed from a wild bird to a human, usually via a domesticated bird like a chicken, or a pig. Sometimes the animal is also infected by a human flu strain, and they combine to produce a variant like the H1N1 swine flu that killed an estimated 284,000 people. People have little or no immunity to new strains, and existing vaccines don’t protect against them, so they spread easily. Flu pandemics have occurred four times in the last 100 years. In 1918, the most devastating of them killed as many as 50 million people. Among humans, flu is transmitted mainly via tiny droplets that they emit when they cough, sneeze or talk, although airborne transmission is thought to be possible.

2. Where does it happen?

All over.

- The first known H5N8 flu virus was detected in Ireland in 1983. In 2014, it emerged in South Korea and resulted in the culling of 600,000 fowl. In the following three years, it caused serious outbreaks on European and North American poultry farms, most likely as a result of the intermingling of migrant ducks, swans and geese at their Arctic breeding grounds. The H5N8 strain is now reported in the Northern Hemisphere almost every year and is behind a fresh wave of outbreaks in Europe, Asia and Africa.

- A strain known as H5N1 that was first detected in 1996 in a farmed goose in southern China began spreading a decade later in poultry across Asia, then to Europe and Africa. Countries in Southeast Asia alone culled 140 million fowl and spent about $10 billion on controlling the virus. The strain was also blamed for the death of more than 450 people, mostly in Indonesia and Egypt.

- H5N2 resulted in the worst animal disease outbreak in the history of the U.S. in 2014-15, with more than 44 million fowl culled. The strains responsible for that outbreak aren’t known to have sickened humans.

- In December 2020 seven people in Russia were infected with the H5N8 strain of bird flu while responding to an outbreak on an egg-producing farm in Astrakhan. Some 101,000 of 900,000 hens died on the farm, according to the World Health Organization, which said the affected workers developed no illness.

- In May 2021, an infection involving a 41-year-old man in China’s eastern province of Jiangsu marked the first appearance of H10N3 bird flu in humans, according to the country’s National Health Commission. There was no evidence that it can spread from human-to-human, although a White House official said it was being closely watched by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

All human infections caused by a novel influenza subtype are notifiable under the WHO’s 2005 International Health Regulations.

3. What do the names mean?

Influenza A viruses are classified into subtypes based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (or “HA” for short) and neuraminidase (or “NA”). The H5N8 virus has HA 5 protein and NA 8 protein. At least 16 hemagglutinins (H1 to H16), and 9 neuraminidases (N1 to N9) subtypes have been found in viruses from birds. Avian flu viruses have also been isolated, although less frequently, from mammalian species including rats, mice, weasels, ferrets, pigs, cats, tigers, dogs and horses as well as humans. The H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes are the main influenza A viruses circulating in people.

4. What can be done?

The more flu viruses spread, the more opportunity they have to mutate in ways that may increase their ability to infect people. That’s why the WHO stresses global surveillance of flu viruses that may affect human or animal health. Virus particles are genetically sequenced, and the information uploaded and shared on the GISAID database, an online portal used to track the evolution and geographic spread of influenza and, more recently, strains of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19.

5. What about flu vaccines?

Public-health experts advocate vaccination as the best protection against flu for people. However, its efficacy varies widely depending on the closeness of the match between that season’s viruses and the vaccine, which is usually reformulated each year. The National Institutes of Health in the U.S. announced in June it was starting a first-in-human trial to assess a so-called universal flu vaccine designed to protect against multiple strains.

The Reference Shelf

- U.N. agencies and World Organization for Animal Health share information on animal influenza strains via their Offlu portal, including H5N8 in migratory birds.

- The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy tracks the latest flu news.

- The U.S. CDC’s latest guidance on influenza.

- The World Health Organization shares information on seasonal flu.

- A QuickTake explainer on influenza viruses and why they pose a pandemic threat, and the swine flu virus in China that has people worried.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.